Walking With Giant Sloths

Take a (virtual) summer road trip to White Sands National Park to explore the fossilized tracks of giant ground sloths

Published August 1, 2024

Even when he vacations, La Brea Tar Pits Fossil Preparator Sean Campbell has fossils on the brain.

So, on a recent family road trip, he made sure to include a couple of paleo pit stops, including New Mexico’s White Sands National Park, famous for its incredible desert vistas—and Ice Age fossil trackways.

While White Sands Park is currently the largest gypsum sand dune on the planet, during the last ice age, the stunning vista was a watery playground for dire wolves, giant sloths, and other animals also found at La Brea Tar Pits. The trackways of Ice Age animals were left in the muddy banks of the ancient Lake Otero—including Harlan’s ground sloth.

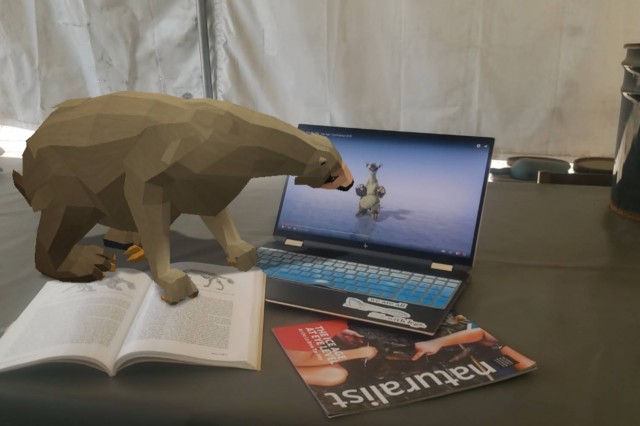

Besides being incredibly cool, these tracks are invaluable evidence of how giant sloths and other animals moved through the Pleistocene landscape, with things like the depth of impression and space between steps revealing the stride of these peculiar extinct animals. Since their discovery, ground sloth tracks have been preserved and studied by experts like White Sands Resource Program Manager David Bustos who generously shared the 3D scans below.

The preserved tracks have provided evidence supporting long-held theories of ground sloth locomotion, namely that these giants transitioned between walking on all fours (in a way unlike anything else on the planet—but more on that later) and standing on their hind legs in a tripod formation, using their tails to balance.

“When they rear up on their hind legs, they use their tail as a tripod to help stabilize their weight, " says Campbell. “A lot of people have argued about whether these animals could definitely have reared up. David Bustos was able to prove that with the trackways in his publication.”

This behavior would have helped giant sloths reach greenery from tall shrubs and trees and might have intimidated any would-be predators. Imagine squaring off with 3,000 pounds of giant sloth on its hind legs at a height of six feet. Some of the tracks even point to human-sloth interaction. Look closely at the scan below and see if anything makes an impression.

“It's very clearly a human footprint inside of a larger sloth's footprint, and it's potentially evidence of some sort of behavioral interaction,” says Campbell. “The human definitely came second and might have been following the sloths or it might have been possibly hunting the sloths.”

“But it's also possible that the human saw the tracks and just thought it would be fun to jump inside and walk in the same footprints as a sloth that maybe came a few hours earlier or a day earlier.” says Campbell.

There’s nothing on Earth that moves like the ground sloths of the Pleistocene, so their tracks are especially revealing. Ground sloths belong to the group of mammals called Xenarthans, which includes animals like their living relatives the tree sloths, anteaters and armadillos. “The fun part about it is that they have this completely different style of walking from most other animals. They use what’s called a pedolateral stance—where the foot is completely rotated inward and they walk on their final digits which are enlarged in comparison to the other digits, especially in the foot. It's just a completely different way of walking and locomotion.”

As part of an image exchange between White Sands and La Brea Tar Pits, Collections Manager Greg Davies scanned a Harlan’s ground sloth foot from the Tar Pits. From the images below, the evidence of feet adapted to their peculiar way of walking is hard to miss.

Scan by Greg Davies

Still from a 3D scan of Harlan's ground sloth hindfoot focusing on a view of the palm

Scan by Greg Davies

Still from 3D scan of Harlan's ground sloth foot from above (medial view)

Scan by Greg Davies

Side view still from 3D scan of Harlan's ground sloth hindfoot

1 of 3

Still from a 3D scan of Harlan's ground sloth hindfoot focusing on a view of the palm

Scan by Greg Davies

Still from 3D scan of Harlan's ground sloth foot from above (medial view)

Scan by Greg Davies

Side view still from 3D scan of Harlan's ground sloth hindfoot

Scan by Greg Davies

“Xenarthrans means strange joints, which actually refer to the extra processes, articulations, and fusions in their lower back, but strange is a good way of describing these animals because there's pretty much nothing that lives like them alive today.” For animals that moved as weirdly as giant sloths, with no real living analogy, fossilized tracks can help us better understand how these giants traversed the land.

Giant Ground Sloth Trackway and Children Jumping

While anyone can visit the Park, seeing the myriad of tracks is reserved for researchers. Campbell reached out to Bustos to see if he could take a look at some of the Ice Age footprints, and Bustos graciously obliged. Bustos had previously visited the Tar Pits for a look at the museum’s extensive collection, and to study the feet and leg bones of the trackmakers found at the Park. As part of his visit, he gave a presentation on the trackways and invited Tar Pits team members to vist the trackways to provide recommendations for track preservation and casting.

Unexcavated Giant Ground Sloth TrackwayGiant Ground Sloth Trackway and Children Jumping

“He got me on a UTV and drove to the north part of the park, which the public is not allowed to visit because it's part of a military co-use area where missiles, bomblets, and other unexploded ordinances have fallen in the park over the years,” says Campbell. Using a tablet, Campbell took lidar scans of the tracks for future research. It was one relatively small step for Campbell, but White Sands’ trackways have made a giant leap in our understanding of giant sloths—and how humans might have interacted with them.