BE ADVISED: The NHM Car Park will be closed on Friday, February 6 in preparation for First Fridays. Parking is available at the Blue Structure Parking Lot at Exposition Park Drive and Figueroa Street. For questions or directions, please call 213.763.3466 or email info@nhm.org.

Misplaced Fears: Rattlesnakes Are Not as Dangerous as Ladders, Trees, Dogs, or Large TVs

In Southern California, rattlesnakes can be seen year round, but Spring and Summer have the most rattlesnake activity.

In Southern California, rattlesnakes can be seen year round, but Spring and Summer have the most rattlesnake activity. This also means that these months generate the most concerns about rattlesnake bites. The good news, however, is that here in the United States, the fear of venomous snakebite seems to far outweigh the actual chance of being bitten. Let’s take a closer look at the statistics behind venomous snakebites.

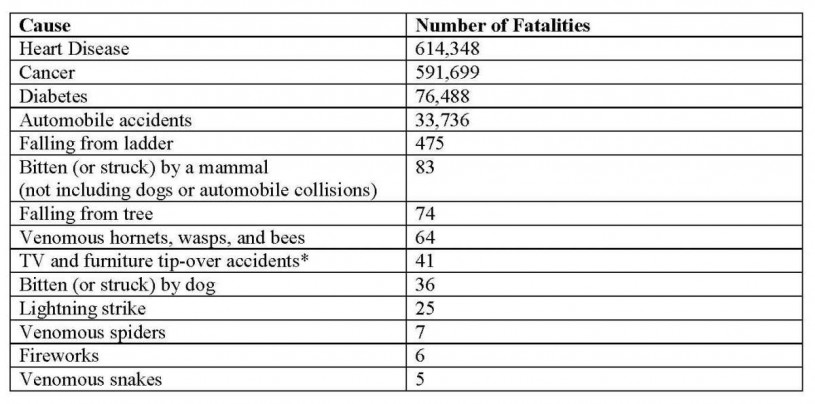

A typical Southern California rattlesnake encounter. Here, a large Southern Pacific Rattlesnake crosses a dirt road in the Santa Monica Mountains. In the U.S., the snakes typically involved in human fatalities include native species like rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths as well as a number of non-native species that are sometimes kept as pets, both legally and illegally, and zoo animals. There are also three species of coral snakes in the U.S., but with their small mouths and fangs, bites to people are rare and usually involve a person handling the snake. To avoid being bitten by a coral snake, follow this simple rule: Don’t pick it up. Here in Southern California, there are seven species of rattlesnakes (making this herpetologist quite happy to live here). Most are found in the deserts, but the Southern Pacific Rattlesnake is common in the foothills and mountains surrounding the larger coastal cities. Each year, around 7,000–8,000 people are bitten by venomous snakes in the U.S. This may sound like a large number, but given that the U.S. population is quickly approaching 324 million people, this represents a tiny proportion of the population (less than 0.0025%). Of these 8,000 or so bites, on average, 5–6 result in fatalities (Table 1). This means, you are 6 times more likely to die from a lightning strike or a dog attack, 8 times more likely to die from a TV set or other large furniture falling on you, 14 times more likely to die falling out of a tree, and 95 times more likely to die falling off a ladder. Of course all of these numbers pale in comparison to risks posed by car accidents (over 30,000 fatalities per year) or of dying of heart disease or cancer, which are the two leading causes of mortality in the U.S. (Table 1). Despite the reality of the low risks from animal attacks in the U.S., snakebites and also shark bites (less than one fatality per year in the U.S.) get a huge amount of attention in the popular press.

How do venomous snakebites happen? The sad reality is that many (very likely most) bites result from poor decisions by people. Bites are divided into two categories, legitimate and illegitimate. If the person never recognized the snake or was in the process of moving away from it when he/she was bit, it is considered legitimate. But if the person recognized the snake but did nothing to move away, it is termed illegitimate. Many of these illegitimate bites involve people handling or harassing the snake. Studies that reviewed U.S. hospital records have found that over 50% of venomous snakebites are illegitimate (up to 67% in one study), meaning the person put her or himself (usually him—see below) in harm’s way. In other words, the snakes are getting blamed for people making bad choices. These illegitimate bites include people keeping venomous pet snakes, religious snake handlers, professional snake handlers, and people who aggravated a snake in the wild such as by trying to catch or kill it. Not surprisingly, most of these illegitimate bites occur to the hands, and the victim is usually a male. In one review of 86 rattlesnake bite victims in Arizona, males accounted for 87% of bite victims. Many of the people who get bitten while intentionally interacting with a venomous snake were also intoxicated at the time (up to 57% of illegitimate bites in one study). For legitimate bites, most occur to the lower extremities because the victim did not see the snake and walked up to it or accidentally stepped on it. The intoxication rate is also much lower for legitimate bites. So what are the take-home messages from these numbers? GET OUTSIDE! Go for a hike, a bike ride, or a jog. Regular exercise helps to prevent heart disease, the number one cause of death in the U.S., and also reduces the risk of diabetes. But on your way to and from the trailhead, drive carefully! Sure there are some critters out there that can inflict pain and possibly even cause death, but if you stay observant, watch your step, and treat wildlife with appropriate respect, you can avoid most of these uncommon threats. And if you do come across a venomous snake, let it be. This seems so obvious, yet it is likely that more than half of the venomous snakebites in the U.S. happen because people didn’t follow this commonsense practice. Take a few steps back and then take some photos. Enjoy the opportunity to see such a beautiful animal. And, of course, if you are in Southern California, please submit that photo to our Reptiles and Amphibians of Southern California citizen science project. For more info: An excellent blog that examines both U.S. and global concerns about venomous snakebite:

Selected references: Curry, S. C., D. Horning, P. Brady, R. Requa, D. B. Kunkel, and M. V. Vance. 1989. "The legitimacy of rattlesnake bites in central Arizona." Annals of Emergency Medicine 18:658–663. Morandi, N., and J. Williams. 1997. "Snakebite injuries: Contributing factors and intentionality of exposure." Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 8: 152–155. Spano, S., F. Macias, B. Snowden, and R. Vohra. 2013. "Snakebite Survivors Club: Retrospective review of rattlesnake bites in Central California." Toxicon 69:38–41.

(Posted by: Greg Pauly)