Aaron Celestian Talks Life on Mars

"On Earth we look for things that are moving or growing to identify life. On Mars, it's not that easy."

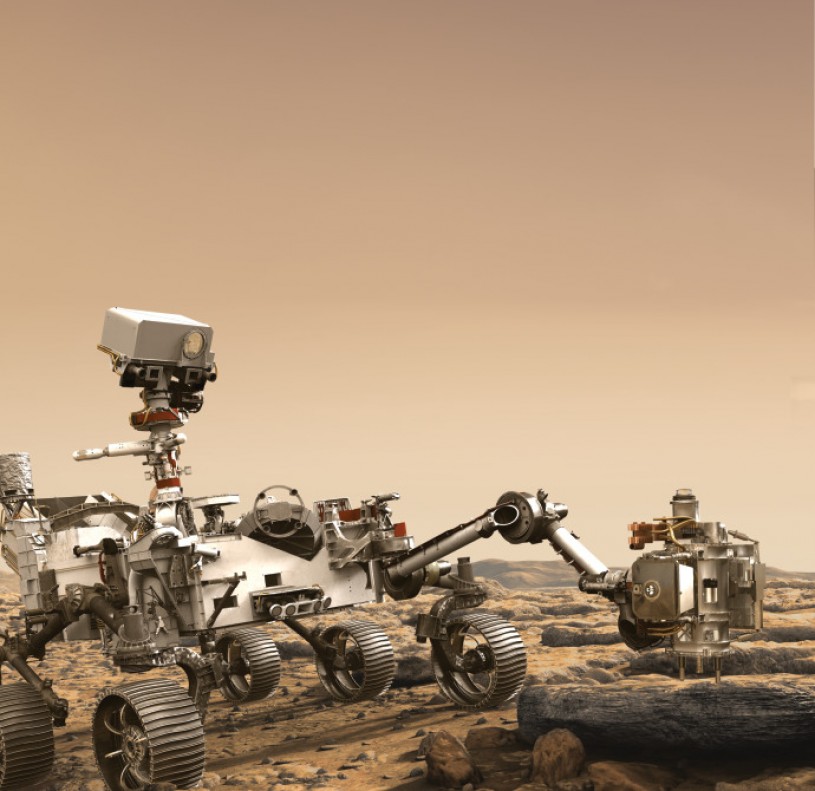

NASA's newest rover, the Mars 2020 Perseverance,

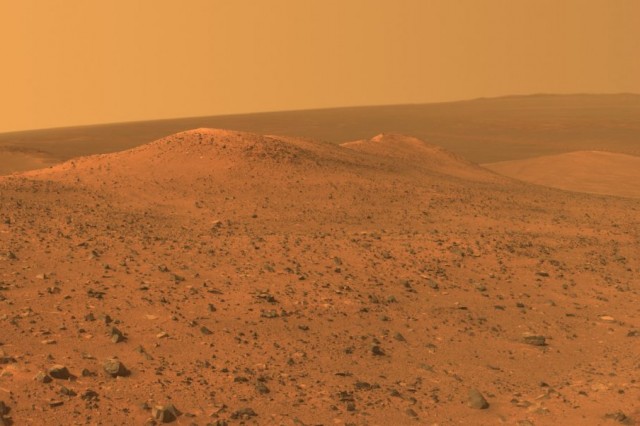

is scheduled to land on the Red Planet on February 18, 2021. According to NASA, while roving Mars, the Perseverance will “search for signs of ancient microbial life, characterize the planet’s geology and climate, collect carefully selected and documented rock and sediment samples for possible return to Earth, all while paving the way for human exploration beyond the Moon.”

One scientist working on this quest is NHMLAC’s own Curator of Mineral Sciences, Dr. Aaron Celestian, who is also an affiliate research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Depending on the outcome of his experiments on Mars, Dr. Celestian and his team would be among the first people on Earth to definitively declare that there is—or was—life on another planet! I spoke with him to get the lowdown on how his research in space has implications here on Earth.

How does it feel to know that you will be doing work on Mars?

Being able to do science on Mars is actually quite strange. When I was a graduate student at Stony Brook University, a couple of my colleagues would send and receive instructions to the rovers on Mars, and I thought it was cool. When I moved to Los Angeles in 2018, one of those colleagues, who is now at JPL, reached out when JPL needed someone with my expertise.

How did you end up being part of this Mars Mission?

The group I am affiliated with at JPL is the Origins and Habitability Laboratory. It’s a permanent research laboratory that is not mission dependent. This means that we are looking, long-term, at what habitability looks like on Mars, the moon, and other extra terrestrial bodies, and how that reflects to the origins of life on Earth.

Which of the seven instruments on the rover will be used in your experiment?

One tool is the PIXL (Planetary Instrument for X-ray Lithochemistry). It is an X-ray spectrometer that can tell us what elements are in the rock. The other tool is the Raman Spectrometer, which is a kind of laser used to fingerprint minerals and other biological chemicals.

How will that help you on this mission?

One question we are exploring in the Origins and Habitability Lab is what does life look like, and how could you use these tools to identify life? It’s tricky because on Earth we look for things that are moving or growing to identify life. On Mars, it's not that easy.

Wow! So your pie in the sky, pardon the pun, would be to use these tools to prove that certain chemicals and minerals were formed from current or extinct organisms on Mars?

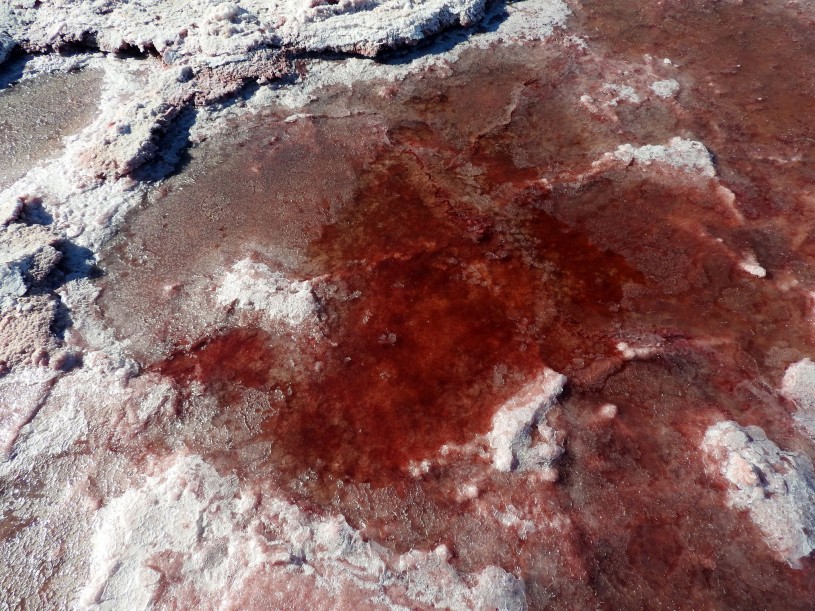

Exactly, and one of the reasons I'm excited about this next mission is that the rover is flying to Jezero Crater, an old evaporated lake. That's where our lab has been studying brine [salty fluid] chemistry, biology, and mineralogy for the last two and a half years. On Earth, carotenoids (an organic chemical that makes carrots orange) are a big part of identifying kinds of life in evaporating lakes. Bacteria (living organisms) are needed to produce these carotenoids to protect themselves from ultraviolet (UV) radiation, and there's a huge UV flux on Mars from the Sun. We think that if something's going to live on Mars for a long period of time, it's going to produce a type of carotenoid, which can last for millions of years. Hopefully, we'll find salts with trapped fluids, and identify biosignatures. If there were carotenoids in these fluid inclusions, I'll get to be one of the first people to say, yes there is life, or was life, on Mars. And that would be "mission accomplished."

Are there special challenges to this work?

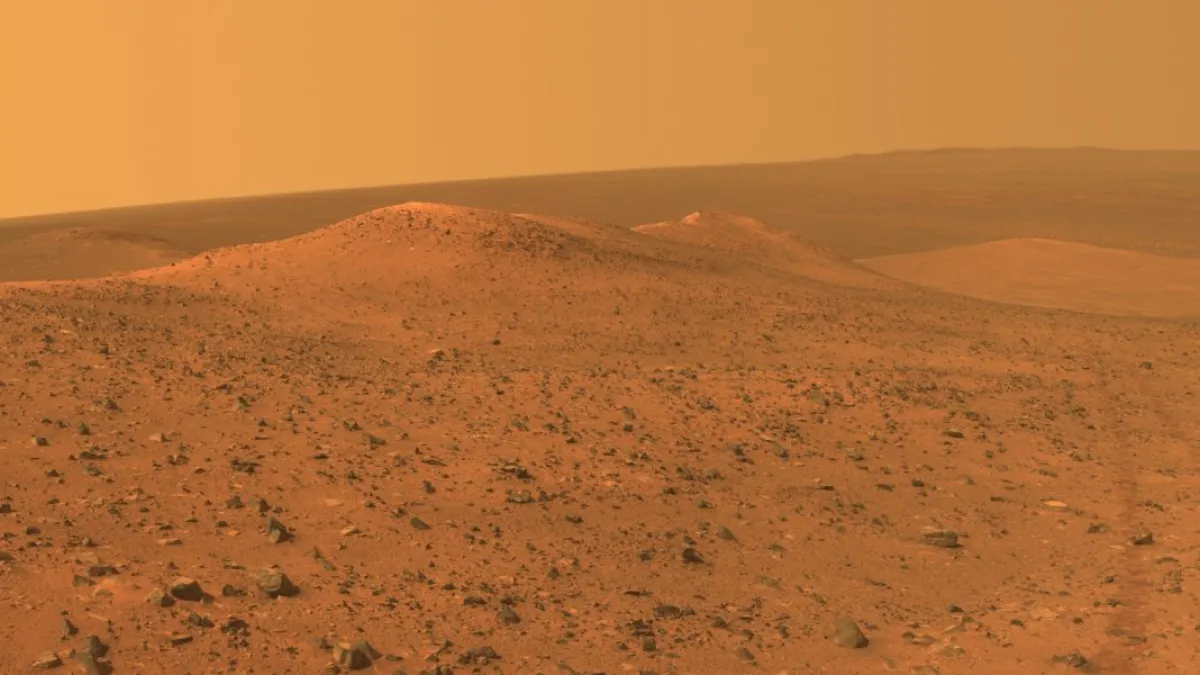

The rock makeup of Mars can be problematic—there's a lot of dust. When you're in the lab, it's easy to clean off a rock and get rid of contaminants. But when you're on Mars, there’s no way of doing that! We also don't know what kind of interference there might be between minerals and salty fluids that may be trapped inside. This will be figured out as it's happening, but we do try and answer as many of these questions as possible ahead of time.

How does this work relate to your Museum work?

We have a huge collection of salts from all over the world at the Museum. A salt is anything that forms from an evaporating liquid; if you evaporate a lake, the minerals left behind that were dissolved are salts. A lot of those salts still have fluids in them. In our lab, we're trying to analyze as many of these salt crystals as possible, to look at what fluids—and bacteria— are trapped in them. Even ones collected 200 years ago have bacteria that are dormant, waiting to come back to life.

This is truly game-changing science! What else excites you about this project?

Well, there is a broader topic about how minerals are a fundamental part of understanding Earth, because Earth is 99.999% minerals. Only a tiny fraction of all materials on Earth are organic, and those materials are dependent on inorganic mineral substrate. The mineral chemistry of a planet is the fundamental common denominator of what life can exist on a planet. So from my perspective as a mineralogist—and I’m extraordinarily biased in this statement—mineral content is probably the most important part of understanding planetary evolution and even the evolution of life.

And, last, question—would you ever want to personally visit Mars?!

Absolutely not. That sounds terrible! I've seen too many bad movies that end up in disaster with people going to Mars. Six to seven months in a spaceship with no gravity, just you and a couple of people. After four months at home because of the pandemic, I'm going crazy. I can't imagine being on a spaceship flying through nothingness. I'm very happy that rovers are doing it!

More About Minerals on Mars

Join us as scientists seek answers to some of the greatest questions in the Cosmos, like: is there life elsewhere on other worlds? What is the origin of life? Since there are not–yet–humans on Mars (but may be in our lifetime!), learn about how robotic spacecraft like rovers, which carry amazing science projects, enable scientists to see, explore, sample and better understand what it’s like.