Backyard Bats of South L.A.

Will bats be the unexpected ambassadors that will connect the urban community of South L.A. to nature?

Published June 21, 2018

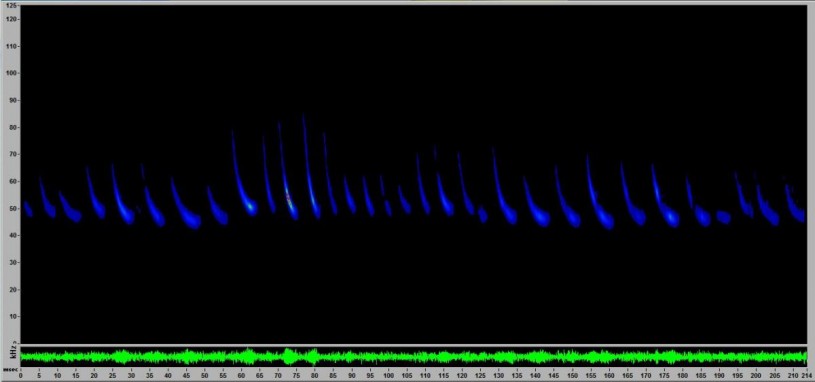

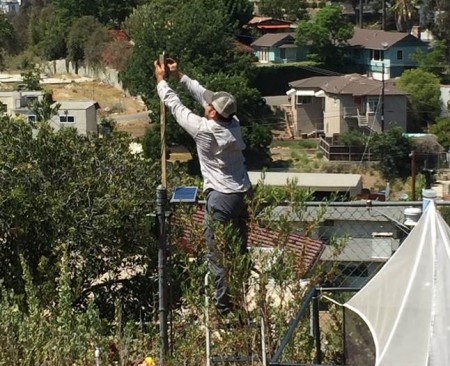

Will bats be the unexpected ambassadors that will connect the urban community of South L.A. to nature? Local wildlife researchers have been able to use specialized acoustic technology to document the presence and activity of this elusive and nocturnal group of mammals. During the 2017 SuperProject, a large-scale urban community science study (learn more about the SuperProject), we used special recording devices called echolocation detectors that help us identify bat species based on their species-specific vocalizations, which are often above the frequency of human hearing. The devices are compact, weatherproof, and have a long battery life, which allow us to deploy them almost anywhere.

However, until recently, this research was limited to large habitat oases, isolated patches of natural habitat that provide shelter, food, and water for wildlife, such as the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, Angeles National Forest, Griffith Park, and Baldwin Hills. Certain bat species, such as the foliage roosting hoary ("hoary" refers to silvery color of fur) bat (Lasiurus cinereus), are "habitat specialists." In other words, they have specific habitat requirements that may only be accommodated in the limited patches of urban wildernesses that exist in the L.A. area. The locally collected bat data hadn’t captured how bats, especially habitat specialists, were using the majority of the Greater L.A. landscape, which is made up of mostly urban and private property.

In 2013, Jim Dines, Mammalogy Collections Manager, and I had some success documenting bats in our Nature Gardens at the Natural History Museum and at the Lake Pit at the La Brea Tar Pits. We even documented a western red bat, which is a habitat specialist and migratory. Although our museums are located in very urban neighborhoods, they are small habitat oases that have habitat features unique to the otherwise park poor areas surrounding the museum. How are bats using or not using the surrounding concrete-filled neighborhoods? I knew the only way to explore this was to begin not only sampling backyards but also sampling backyards in different neighborhoods with varied environments and proximity to larger green spaces.

In 2016, I joined an innovative NHM project called the SuperProject that was already engaging entire regions of L.A. community scientists in wildlife exploration. Participants in the SuperProject were using iNaturalist to document wildlife that they were able to spot during the day in their neighborhoods, and some participants had yards that hosted a flying insect trap, called a malaise trap. At the tail end of their first sampling season, I was able to install some bat echolocation detectors at those sites after receiving a generous grant from Wildlife Acoustics.

The data collected the first year was eye opening. We not only documented bats in every backyard, but in most backyards we detected bats that are California Species of Special Concern (identified as vulnerable but not yet classified as threatened or endangered by the state of California). These bats are uncommon to the area, and we had previously thought that they were too urban sensitive to use urban neighborhoods or possibly required habitat that didn’t exist in the L.A. area. However, the majority of the first sample of backyards were in suburban parts of Los Angeles, so I was very curious to know what we’d find the next year when we moved our SuperProject study area to South L.A., one of the most park-deprived urban neighborhoods out there.

Did bats finally meet their urbanization match? Were these going to be the first Los Angeles locations in our study that wouldn’t turn up any bats? How impenetrable is South L.A.? These questions were on my mind as we surveyed six South L.A. backyards in 2017 and 2018. Not only did all of them detect bats, but some of the most urban sites within South L.A. detected multiple species! The ability to gather some of the first bat data for this area was an exciting honor in itself, but being able to share this information with members of these communities were some of the most rewarding moments of my career. I shared data with most of the site hosts via e-mail and at our end of the year SuperProject participant dinner, but there was one family that received the news in the comfort of their own home.

The results that I shared came as a pleasant surprise to Andrea Robateau and her son Armand, especially as they learned the cool behaviors of the species detected in their yards, in addition to the important ecosystem services they provide as consumers of nocturnal flying insects. The species they detected during their month-long deployment (detector attached to their play structure) were Mexican free tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis), canyon bats (Parastrellus hesperus), and hoary bats. I had the unique opportunity to use museum specimens to show them examples of the critters that flew over their backyard at night. Sharing these findings made the connection between their backyard and the natural world more tangible and impactful than any of us expected and it was a truly wonderful moment that I will never forget.

This story from SuperProject 2017 is only one example of how mutually engaging and educational the SuperProject experience can be for both participants and scientists. The search for urban wildlife in South L.A. continues as we survey the region more extensively beginning in September 2018! If you want to be immersed in urban wildlife discovery and you live south of the 10 Freeway, between I-405/Hawthorne Blvd. and the 710 to the beach, please click here to learn more.