High-Flying Scientists

Nearly a century ago, Hildegarde Howard, an accomplished avian paleontologist, began her career at the museums. She ultimately reached one of the most elevated perches—Curator of Science.

Published March 6, 2023

Almost a century ago, women were not allowed to participate in university field trips that took place off campus, and it was a common belief that science was a field predominantly reserved for men. However, Hildegarde Howard, a young biology student at the Southern Branch of the University of California, now known as UCLA, was not deterred by these societal limitations. Her flight path was guided by curiosity.

Hildegarde first became captivated by the sciences in Ms. Pirie Davidson’s biology class, and eventually became Ms. Davidson’s lab assistant. She was then offered a position as a part-time day laborer sorting fossils for renowned paleontologist Chester Stock at the Museum of Science, History, and Art of Los Angeles County (now the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County) at Rancho La Brea.

Rancho La Brea, which is also known as La Brea Tar Pits, is a location in the Hancock Park neighborhood of Los Angeles where natural asphalt has been seeping out of the ground for thousands of years. This sticky, black substance was often concealed by leaves, soil, or water and was thick enough to ensnare animals who unintentionally stepped into it. These animals attracted bigger scavenger creatures such as dire wolves, saber-toothed cats, and birds of prey, who came to feed on them. Unfortunately, many of these bigger animals also got caught in the asphalt. As time passed, additional layers of asphalt would accumulate on top of the animals, causing the cycle to repeat itself.

During the early development of Los Angeles, landowners allowed scientists including Stock to dig and do research on fossils at Rancho La Brea. In 1924, the land was donated to the museum. Hildegarde finished counting her first lot of avian fossils and had identified over 4,000 individual birds in the pits! The large number of fossils found shows that birds suffered a similar fate as mammals in the pits and in a similar manner. The pits captured flora and fauna indiscriminately and left a sticky snapshot of the diversity of life over time in Los Angeles. Hildegarde was enraptured. She found her life’s passion in paleontology.

The pits captured flora and fauna indiscriminately and left a sticky snapshot of the diversity of life over time in Los Angeles. Hildegarde was enraptured. She found her life’s passion in paleontology.

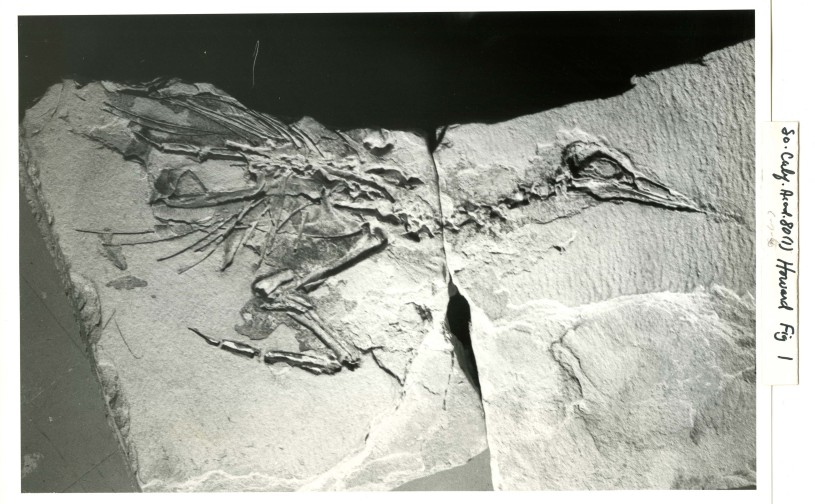

When Hildegarde graduated, a part-time research associate position was waiting for her at Rancho La Brea. Hildegarde’s meticulous work measuring and examining avian fossils led to her first published paper on the extinct California turkey, Parapavo californicus, which was a fossilized and extinct turkey found at the Rancho La Brea site. She described the extinct bird from more than 800 specimens. This abundance of specimens required her to account for osteological (bone) variation within the species and impressed her mentor, who allowed the paper to count as credit toward a Master’s degree, which she would finish two years later.

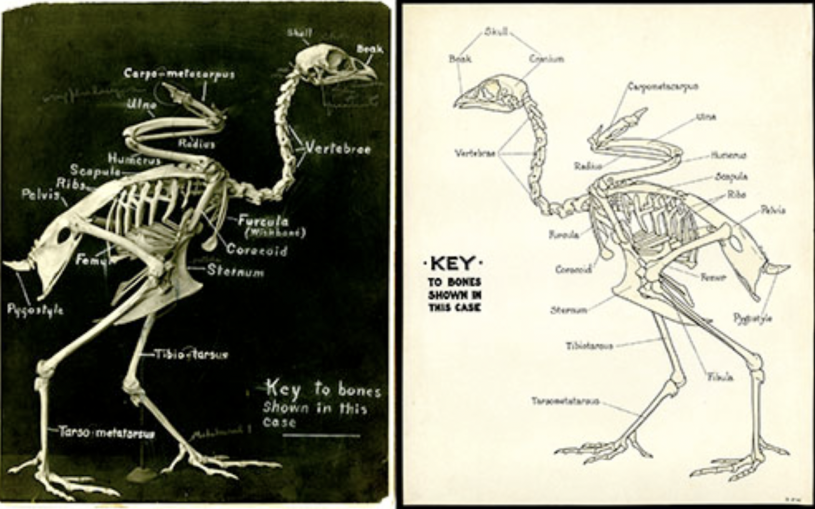

Her dissertation, The Avifauna of Emeryville Shellmound, included drawings of fossil birds with clearly labeled osteological features. The creation of a standardized terminology was a major advancement for avian osteology because it provided a consistent framework for researchers to use as a reference point, marking the first time such a framework had been established. Howard’s illustration would remain the principal reference until 1979 when Nomina Anatomica Avium was published.

Hildegarde continued to work at the museum over school breaks while completing her advanced degrees. In 1929, Howard received her Ph.D. and became Dr. Howard. She returned once again to the museum, this time as a junior clerk tasked with curating the fossils from Rancho La Brea and the research birds that had been collected in the American Southwest.

In 1938, towards the end of the Depression, Dr. Howard was given a promotion to senior curator. However, despite this promotion and auspicious title change, she did not receive an increase in pay from her previous role as a junior assistant. Nevertheless, she continued to work diligently and produced a remarkable amount of work. Between 1929 and 1939, Dr. Howard published twenty-four papers on fossil birds in the American Southwest. In 1942, the prehistoric bird fossils that she had collected were displayed in the Museum's Hancock Hall.

In 1944, Dr. Howard was promoted to the position of curator of Avian Paleontology at the museum. She held this position until 1951 when she was promoted to Chief Curator of Science. During her time as Chief Curator, Dr. Howard not only continued to publish new work and further her research but also served as the head of the Science Division at the museum. Jean Delacour, the museum director throughout the bulk of Dr. Howard’s tenure, wrote highly of her work and leadership during this time. He stated, “I sincerely believe that no one could have done it better.”

In 1946, just two years after becoming the curator of Avian Paleontology, Dr. Howard received the Brewster Medal for outstanding research in ornithology. She was the first woman to receive this prestigious award from the American Ornithologists Union. By the time of her retirement in 1961, Dr. Howard had described two families, six genera, 23 species, and one subspecies, published 99 papers of avian fossils, and embraced the technology of Carbon-14 dating to target the age of specimens at Rancho La Brea and help create a timeline of avian extinctions during the late Pleistocene.

Never one to slow down, Dr. Howard stayed on as an emeritus curator and continued her research. As California continued to rapidly develop, marine Miocene and Pliocene strata were exposed. Retirement allowed Howard to explore her interests in depth and pursue her intellectual curiosity without the pressures of a demanding work schedule. Howard could devote herself full-time to both the fossil birds of the American Southwest and Tertiary marine birds of Southern California. She said of retirement, “When your life’s work is a hobby, you don’t need other hobbies.”

Retirement proved to be a fruitful time for Dr. Howard, where she could immerse herself in extensive research. During this period, she was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship, authored over forty additional papers, and identified and described a new family, seven genera, 34 species, and one more subspecies. These impressive accomplishments demonstrate Dr. Howard's deep commitment and enthusiasm for her area of expertise.

Dr. Howard was a very private individual who preferred to stay out of the public eye, revealing very little about herself apart from her ardor for avian paleontology. However, there are a few tidbits of information available that paint a picture of her life outside of her work. One certain thing is that she met her soulmate, Henry Anson Wylde, on the fateful day they were both sorting fossils at Rancho La Brea. He too was a day laborer who would eventually rise to the position of Chief of Museum Exhibits. They tied the knot in 1930 and remained inseparable until Henry's passing in 1984.

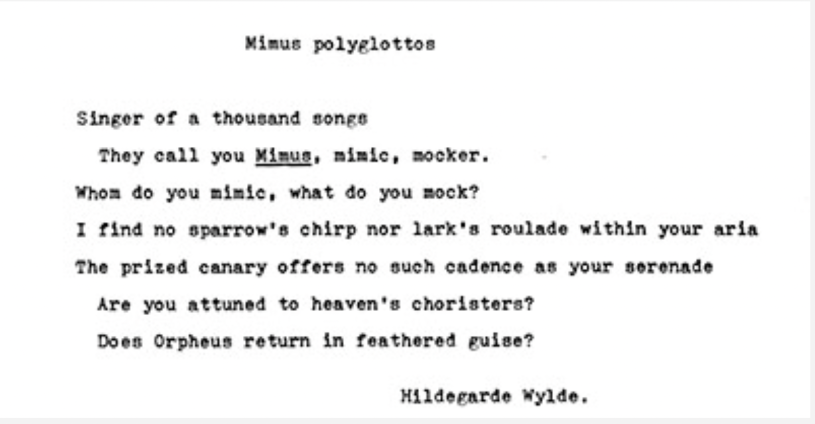

In addition to her love for birds, it is known that after retirement, Hildegarde discovered another medium for her creativity: poetry. However, her mind always soared amongst the birds, even in her private musings.

Dr. Hildegarde Howard was a remarkable person who lived an exceptional life. She was an expert in the study of avian paleontology, and her work in this field is highly respected. She thrived despite societal limitations and discrimination, and her unwavering curiosity and determination allowed her to become an unequivocally groundbreaking paleontologist. In 1984, at the age of 83, Dr. Howard published her last paper called "Middle Miocene Marine Birds from the Foothills of the Santa Ana Mountains, Orange County, California." This paper was a significant contribution to our understanding of ancient birds and their habitats.

Unfortunately, Dr. Howard passed away on February 28, 1998. However, her work and legacy in the field of avian paleontology will never be forgotten. She was a true trailblazer in her field, and her contributions will continue to inspire and inform future generations of scientists.

The Flight Path

Howard was an inspiration for many women scientists for her accomplishments, scholarship, and leadership over the last century. Assistant Curator of Ornithology Allison Shultz said Howard is “certainly someone to be admired, especially in a time when there were very few female museum curators (I mean, there still are very few now!)” Dr. Emily Lindsey, the Associate Curator and Excavation Site Director at La Brea Tar Pits is also a fan of this La Brea Tar Pits pioneer. “Over the course of her nearly seven-decade research career, Dr. Howard described 57 new species of birds and published about 150 scientific papers, which is pretty intimidating!” says Dr. Emily Lindsey, the Associate Curator and Excavation Site Director at La Brea Tar Pits.

“She was the first person to systematically survey the important avifaunal assemblage of Rancho La Brea, and one of the only paleontologists to have considered the widespread extinctions of large birds that accompanied the better-known large mammal extinctions at the end of the Pleistocene epoch. We must build on her foundational work in this area if we are to ever fully understand the causes of the Ice Age extinctions and their continuing impacts on modern ecosystems."