A Matrix of Matriarchs

An ex-enslaved person who won her freedom, the first Black woman to own a U.S. newspaper and to be nominated for vice president, and other glass-ceiling-shattering California women rising up in L.A. today.

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified on August 18, 1920, officially guaranteeing women the right to vote. Experience the Museum's Rise Up L.A. exhibition, which highlights Los Angeles women who continue to advocate for equality through everyday acts of bravery and courage.

Biddy Mason: Her Stand for Freedom

Biddy Mason’s life story reads like great fiction: a terrible struggle, a fight for justice, adventure, and then remarkable success. It all started with young love. Charles Owens, a young free black man, fell for Mason’s daughter Ellen. It was a time when slave-owning whites who migrated to California retained “ownership” over enslaved Black people through indentured servitude. When, in 1855, Mason’s slavemaster decided to move her and her children along with his family to Texas, where there was no such thing as free people, Owens took action. Enlisting his father in the effort, Owens rallied the local enforcement, along with a posse of vaqueros (cowboys), who together insisted that Mason and her people had a right to remain free and in California.

That is how Biddy Mason came to petition a California judge to free herself and her children. Mason knew the stakes. She’d been born into Mississippi’s plantation system and feared the tortures of slavery and reprisals her children would face if they were taken to Texas. As a woman of color, she was not allowed to speak in court. But even in a time of pervasive injustice, the law broke her way. While the nation was divided, the judge said the law of California was clear: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, unless for the punishment of crimes, shall ever be tolerated in this State."

DELIVERING A LOS ANGELES LEGACY

After her emancipation, Mason accepted shelter with the Owens’ family, finding work as a midwife and nurse, serving in a physician’s office on Main Street and even in the same county jail in which she’d taken refuge with 14 other enslaved people fighting for freedom. She braved a smallpox epidemic during the 1860s, risking her life to tend to the sick and earned a reputation as an excellent midwife, delivering hundreds of babies over her career. After ten years of hard work and frugal living, Mason spent $250 to become one of the first Black women to own property in Los Angeles. Running between Spring Street and what is now Broadway, Mason’s homestead occupied a part of Los Angeles with more gardens and vineyards than paved streets, a fitting place to gather her family, nurture their ambitions, and grow her own.

Mason leveraged her wealth as a property owner to buy more property, and continued her calling to help people. She gave room and board to the destitute and visited the imprisoned. Just as she built generational wealth, Mason invested in institutions to serve the community; she organized the first African American Church in Los Angeles, a traveler’s aid center and a primary school for young black people. Mason’s remarkable spirit was evidenced in the words she spoke to her granddaughter: “If you hold your hand closed, Gladys, nothing good can come in. The open hand is blessed, for it gives in abundance, even as it receives."

This story relies heavily on Dolores Hayden’s The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History, an excellent resource to learn more about how Mason and other underrepresented people helped shape Los Angeles.

By Tyler Hayden

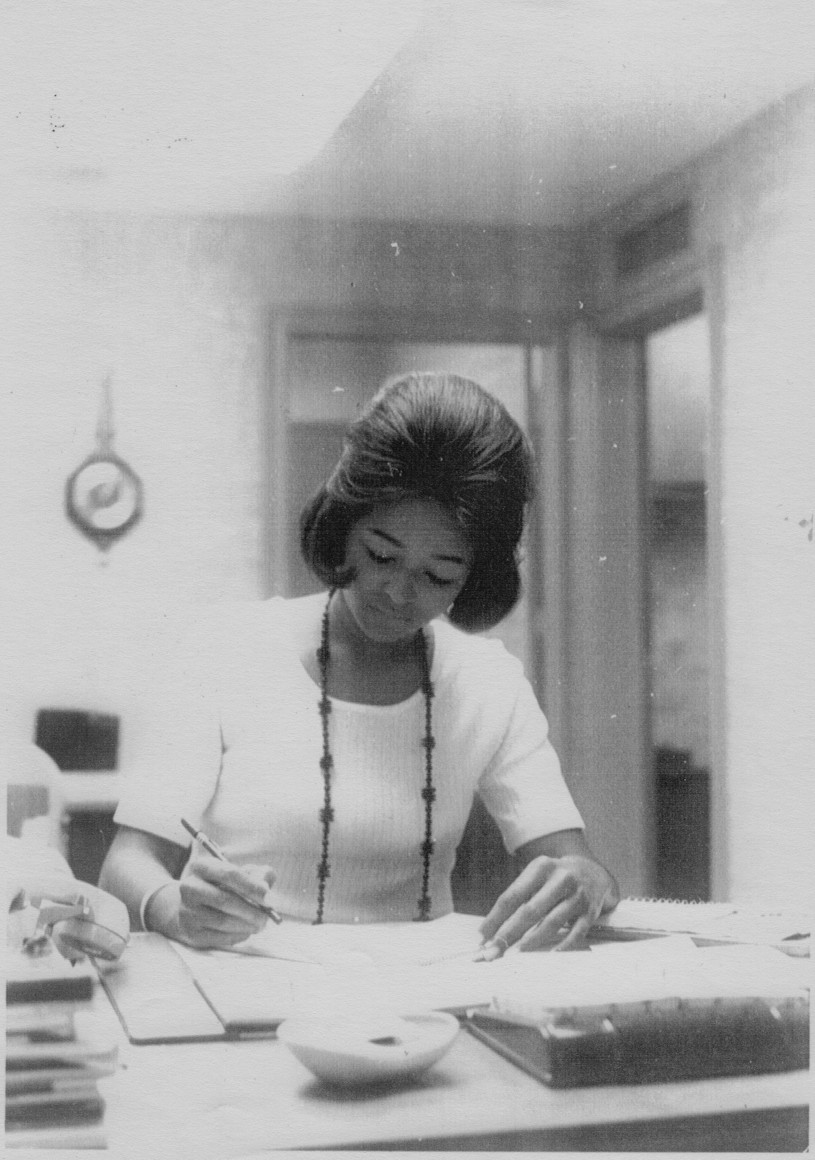

Charlotta Bass: A Life of Inaugurals

Kamala Harris, the Democratic Senator from California, made history recently as the first African American and first South Asian American woman from a major party to be nominated for and then elected vice president. She wasn’t the first Black woman to be tapped as a running mate in a U.S. presidential campaign, however. That barrier-breaking title goes to Charlotta Bass, whose long-shot candidacy was with the Progressive Party in 1952.

In her acceptance speech at that party's convention in Chicago, Bass spoke, with gravitas, about her ascent to that political stratosphere. “I stand before you with great pride. This is a historic moment in American political life. Historic for myself, for my people, for all women. For the first time in the history of this nation a political party has chosen a Negro woman for the second highest office in the land. It is a great honor to be chosen as a pioneer. And a great responsibility.”

SOCIAL JUSTICE JOURNALIST

Before she felt that call to enter the political arena, she was a keen observer of it from the press box. In 1910, with degrees from Ivy League schools Brown University and Columbia University in hand, the native South Carolinian moved to Los Angeles and joined the staff of the California Eagle, according to the historian Denise Lynn. She and her husband, Joseph Blackburn Bass, became co-editors and publishers of the influential newspaper, which had a circulation of 60,000, the largest of any African-American newspaper in the West. After her husband died, she assumed full control in 1934, becoming the first African American woman to own and operate a newspaper in the U.S., according to Rodger Streitmatter, the author of Raising Her Voice: African-American Women Journalists Who Changed History. The Eagle combined practical community news items about local happenings with a civil rights mission. Its small, scrappy staff unearthed stories that exposed racial bias in society. In her commentaries, Bass advocated for housing rights, labor rights, voting rights, and opposing police brutality, and she was a formidable denouncer of the Ku Klux Klan.

While Bass had allegiances to the Democrat and Republican parties during her lifetime, she ultimately left both as she believed they had neglected Black empowerment and women’s rights. She embraced the Progressive Party with its anti-militarism and pro-justice platform. In her speech at the 1952 Progressive Party convention, her emphatic promise to be a fighter for justice seems now to echo the words Harris spoke when she accepted presidential nominee Joe Biden’s invitation to be his running mate on the 2020 Democratic Party ticket. “I am strengthened by thousands on thousands of pioneers who stand by my side and look over my shoulder—those who have led the fight for freedom—those who led the fight for women’s rights—those who have been in the front line fighting for peace and justice and equality everywhere,” said Bass. “These pioneers, the living and the dead, men and women, black and white, give me strength and a new sense of dedication.”

By Jessica Portner

Dorsay Dujan: A Voice From L.A.'s Women's Movement

On the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment, in conjunction with the Rise Up L.A. exhibition at NHM, we conducted an Oral Stories Project. Among the dozens of women interviewed was Dorsay Dujan, a 75-year-old Jamaican-American Angeleno who talked about her work in the show business world of the 1960s and the women who were her role models along the way.

GENDER INEQUALITY WAS A GIVEN GROWING UP

"There was definitely a different set of rules for girls. The opportunity to become whatever you wanted to be wasn't exactly given to us. So it was something that we really had to find from within ourselves, or from other friends that we met who would support us with what our dreams were. And then at work, too. Going to work. In those days, I went for jobs or had jobs where I would be told, well, we can't really hire you for this position because the boss would prefer a blonde at the reception desk. And on one job, I'll never forget this, I was asked to train this young man. And it was a brokerage firm. And I was asked to train him to do whatever it was I was doing at the time. I was helping them to set up for making trades the next morning and that sort of thing. And I trained him, and my boss called me into the office and said, ‘you've done a really great job in training, but you know, he's getting married. And he's going to have a family. And I'm going to have to let you go.’ And that was the first time that I got that type of slap in the face. And that was quite disconcerting."

A THEATRICAL NATURE

"I always loved show business, and I always thought I would want to be a producer. So I actually learned to pull the neighborhood kids together to have talent shows, and we would go Christmas caroling… And it actually worked out well, because in my life, that's pretty much what I ended up doing anyway. And so I think we do find what our path is early on, even though we're not aware of it at the time. All those things really taught me how to collaborate, because this little kid had to do this, another one had to do something else, and then we all come together to make this little show happen."

LESSONS THAT STICK

"I produced trade shows and special events, and conventions around the country, and even worked on some projects that were overseas. The first job that I had was at the William Morris office, a theatrical booking agency. I didn't even know it at the time, but that was the most perfect place for me to have my very first job. I started as a file clerk. And it was an extraordinary experience…I got to know the secretaries around the building, because I was delivering all of these messages, the teletype. They would tell me when Gregory Peck was coming in. And then I would run into Steve McQueen in a hallway. But all of these amazing, creative people and these agents who were the big guns in those days, they were the ones that made the stars. Everything I learned there has stayed with me. And the first thing was that nothing is impossible."