The Ofrenda Community Project, Andrea's Reflection

Reverberation of Friendliness

A collaboration between the Museum & WriteGirl

Community voices within Museum exhibits bring added value, perspectives, and spirit. In partnership with WriteGirl, a creative writing and mentoring organization that promotes creativity and critical thinking, the Community Engagement team at the Museum created The Ofrenda Community Project. Participants received at-home storytelling kits anchored in the ofrenda or altar located in the Becoming Los Angeles exhibition. WriteGirl youth selected an inspiration object in the ofrenda that they felt drawn to and created a memory map based on that object to explore connections and meaning in their personal experiences. They then crafted their own object to add to the ofrenda and developed a creative writing piece derived from the memory map activity.

Andrea's inspiration object was the photo of Brian Kito in his family-owned and operated store, Fugetsu-Do, pictured below. Fugetsu-Do is a Japanese mochi and manju confectionery in the Little Tokyo area of Los Angeles, California since 1903.

Meet Andrea Ohlsen-Esparza, WriteGirl Staff

Andrea Ohlsen-Esparza, Bold Ink Writers Program Coordinator, develops curriculum, leads creative writing workshops and oversees participation of teaching artists and special guests for WriteGirl’s classroom-based programs. She has teaching experience in a variety of classroom settings, from leading bilingual literacy classes for parents to creating curriculum for preschoolers. She is a trained improvisational actor/comedian and co-hosts frequent live shows. She has a BA in Anthropology from California State University, Dominguez Hills with a Minor in Theater Performance.

Reverberation of Friendliness

This photo from the ofrenda in the Becoming Los Angeles exhibit reminds me so much of my own father. As I read the caption, I realize it is a photo of a man named Brian Kito, pictured in his family-owned and operated mochi store, which opened in 1903.

As I read the caption again, I find myself feeling a mix of love, reminiscence and a tinge of longing. My family owns a one-cashier-kind-of-store in Huntington Park, Los Angeles, called Mi Viejo San Juan Market. My family and I tenderly call it La Tienda.

When you enter La Tienda, you have to walk through long plastic rectangles and a giant blowing fan. The hum of the fan says, “Buenos Dias,” to you and, at that moment, you decide to risk the frizzing of your hair because you know that inside you will find a 3-foot stack of fresh Semita Alta, platanos in their various stages of life (verdes, amarillos and super maduros) and a metaphorical me (ages 12, 16, 26) in the various stages of my life.

There was always immense joy in our customers’ voices when they would see my dad at the counter. They would exclaim, “Rigo! Dime que ya es la temporada de las guanabanas?!” (“Rigo! Tell me that the soursops are in season!”) It’s interesting that you can gauge how long people have known each other by the way someone says your name. There’s a reverberation of friendliness and years of sharing stories pass through the air, slightly clipping your ears with a tone of, “Yes, I belong here.”

As he placed a large, bright green amorphous shape onto the produce scale, my dad tells his customer that this soursop is going to cost them $16.43. The customer always does a theatrical closed-toothed gasp, and then smiles and giggles as if they caught a cat endearingly licking a snowcone. I saw this repeated hundreds of times, but my dad would always change the script. He would ask them questions such as, “Did your daughter get the job that she wanted? ...Oh, I actually have another client that works in real estate, I’ll let them know about your daughter.” At age 12, I was not completely aware what these transactions meant.

When it was my turn to work at La Tienda, I started to understand the power that came from being the one at the counter.

“Buenas Tardes! Please tell me that you still sell mangos tiernitos?”

“Yes! Claro que si.” I would place the bright green baby mangoes that were half the size of my palm onto the produce scale. I noticed that the mangoes’ reflections were blurred on the scratched chrome-like surface.

“Your total is $22.44.” Here it comes! The moment where I get to be part of the script!

Gasp...laughter...and then I ask, “What are you doing for the holidays this weekend?” And in return I might receive a love note to their home country, a joke about a toad that somehow turns into a philosophical anecdote or some career advice, or a mix of all of these things.

When the customer leaves, I find myself looking at the produce scale. The buttons are worn from the countless inputting of numbers, the countless inputting of stories, and all the transactions and conversations.

This produce scale is my offering for our collective ofrenda. My father passed away in 2013, and I continued to work at the tienda all throughout my college years. Sometimes I had clients visiting from Washington, or who had driven from Bakersfield, because they missed having fresh hojas de platano to wrap their tamales. When I would tell them that my father was no longer with us, they would say his name, “Rigo,” and tell me about the time he let them buy groceries on credit for a month because they had been unemployed. If he found out they were pregnant he made sure to have a secret stash of fresh chipilin just for them. He would sing to children when they walked into the store.

After my father died, I must have told a hundred people about his passing. They all had a story for me.

I think about the weight of those stories as I gaze at the proud look of Brian Kito holding his family's mochi in the picture. It is the same proud look I get, as well as my brothers, when we stand behind the counter, where my father stood.

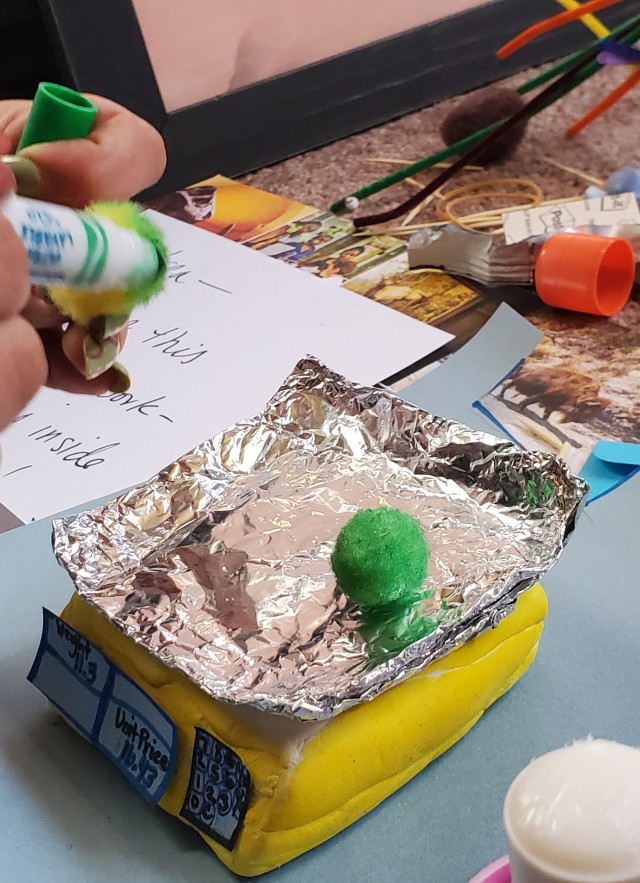

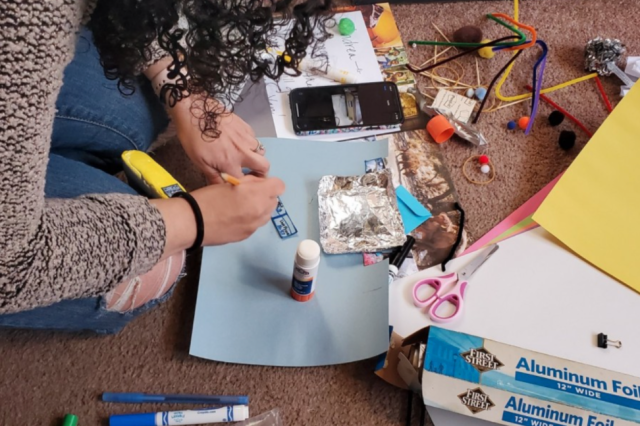

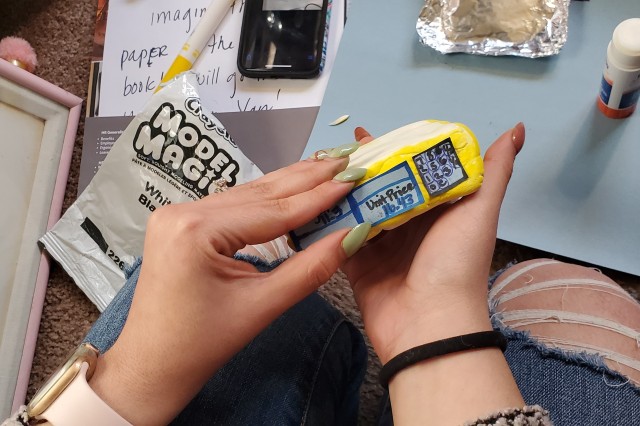

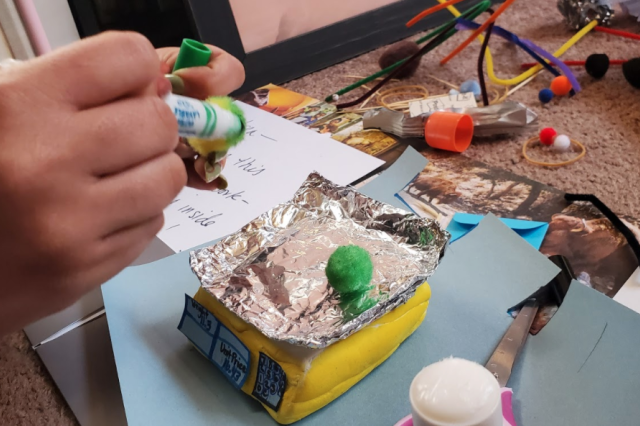

Andrea DOCUMENTS THE MAKING OF HER OFRENDA OBJECT

My cat, U.V., wants to help and, lucky for me, her crafting skills are reputable!

The white Model Magic clay seems to disappear in my hands in the sunlight.

Customers at La Tienda sometimes noticed that we don’t scan barcodes and that very few prices are marked. They’d ask me, “how can you remember all those numbers,” and I’d reply, “because I had to!”

I had an employee from La Tienda text me 5 different shots of the produce scale, all taken at different angles, so I could recreate it accurately.

These fluffy versions of mango tiernitos are pretending to be extremely sour and almost crunchy – you can eat them with salt and lime.

This process was relaxing and comforting – I was able to turn a cherished memory into something physical and real.

Behind me is a photo I have of my father in my apartment and a billiard ball from the house I grew up in.

1 of 1

My cat, U.V., wants to help and, lucky for me, her crafting skills are reputable!

The white Model Magic clay seems to disappear in my hands in the sunlight.

Customers at La Tienda sometimes noticed that we don’t scan barcodes and that very few prices are marked. They’d ask me, “how can you remember all those numbers,” and I’d reply, “because I had to!”

I had an employee from La Tienda text me 5 different shots of the produce scale, all taken at different angles, so I could recreate it accurately.

These fluffy versions of mango tiernitos are pretending to be extremely sour and almost crunchy – you can eat them with salt and lime.

This process was relaxing and comforting – I was able to turn a cherished memory into something physical and real.

Behind me is a photo I have of my father in my apartment and a billiard ball from the house I grew up in.