The marine side of NHM kicked into high gear when we hosted a two-week get-together in August for a star team of biologists from around the country: the Los Angeles Urban Ocean Expedition 2019. The goal was to work together as a group to collect, identify, and genetically “barcode” thousands of marine invertebrate specimens, working every day of the week.

Such a big science effort also called for public participation, and more than 400 visitors came to the expedition’s “pop-up lab.” You may have noticed that there’s no seashore at Exposition Park. Hence, this expedition was headquartered in San Pedro, at AltaSea, a dockside facility dedicated to ocean research, education, and business incubation.

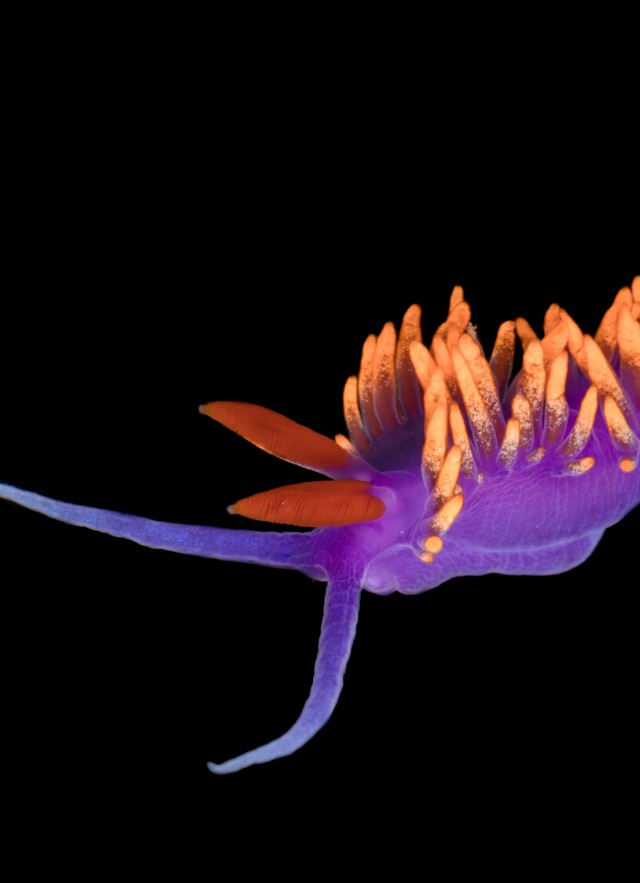

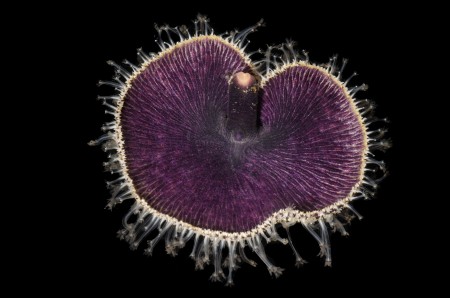

Every day for two weeks, multiple ships brought an array of freshly collected marine specimens to the eager team of working biologists. The biology team’s job was to identify, photograph, catalog, and tissue-sample as many specimens as possible.

But why? What’s going to result from this big effort? It turns out that, although NHM has (literally) millions of specimens of marine invertebrates (ocean animals without backbones such as snails, crabs, and worms), the vast majority of them are not available for modern biology’s killer app: genetic sequencing. Because they were first preserved in formalin (rather than directly into ethanol, as we collect today), their DNA is too fragmented to make genetic sequencing practical. So, to get access to the genetic treasure trove inside marine animals, we need new samples collected specifically to keep DNA intact. That was the focus of the expedition: sampling as diverse an array of marine species as possible, identified immediately by the best experts, thanks to extraordinary support from local government agencies for use of their research vessels, divers, and staff.

But, in turn, why is that useful? NHM’s Diversity Initiative for the Southern California Ocean (DISCO) is helping develop a modern genetic technology, “environmental DNA” (or “eDNA”). All animals (and plants and algae) shed DNA into the environment. So we can take a sample of the environment—say, a cup of seawater—and sequence all the unique strands of DNA in that seawater. That gives us an inventory of the genetic diversity that has been near that water sample.

Here’s the tricky part, though: We have the inventory of sequences from an eDNA sample, but to decode what species each sequence represents, we need a reference database of sequences. To build that database, identified specimens of known species have had special “barcode” genes sequenced and registered as references. That database is the lookup table that turns our eDNA inventory into a species list.

And that’s why DISCO hosted this expedition. Although we’ve already registered many hundreds of reference barcodes, this two week intensive experience supercharged the rate we are populating the reference database. Thanks to the expedition, with the help of dozens of scientists and other participants, we now have thousands more reference sequences. Life in the ocean, as well as on land, is responding to climate change. This expedition has helped make environmental DNA an even more valuable tool for tracking changes in our coast’s marine life as we learn to manage our changing ocean.

Dean Pentcheff is Program Coordinator of NHM’s DISCO program. As part of the DISCO group, he shared in creating and hosting the expedition. He has yet to find anything more fun than being in the ocean gathering data for science.