Unexpected Animal Parts

Published September 16, 2020

Sometimes items in the Anthropology collections are surprising on sight and sometimes it’s learning what they are made of that offers the surprise.

In a collection of material from indigenous cultures around the world, it is astounding to see the variety of animal parts, carefully collected and included in the fabrication of tools, bags, and ornaments for both ceremonial and everyday use. At times these parts are selected for their difficulty to acquire but more often their use is practical, taking advantage of the resources available in the surrounding environments of their makers.

In the following examples, the creativity demonstrated in re-purposing these animal parts will blow your mind!

Intestines

A source of waterproof material that visitors often find shocking is intestine, specifically seal or walrus intestine where it is most used in Arctic regions. Since it sits within the body, intestine is naturally waterproof, and once sliced down the side, flattened, and cleaned, it renders flexible strips that can be stitched together to create an impermeable fabric.

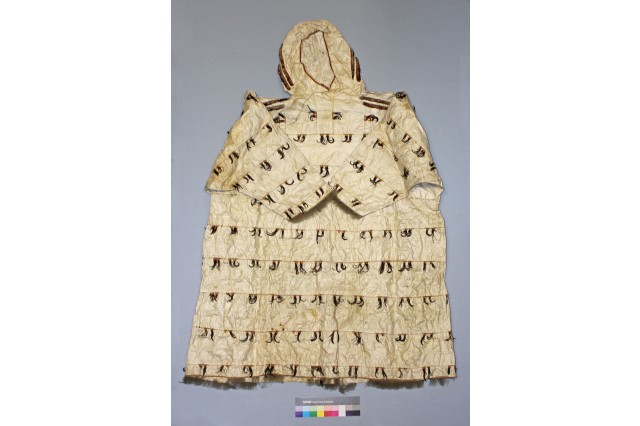

This rain parka is made of strips of bleached intestine that have been stitched together horizontally. It is decorated at intervals with small brown crested auklet feathers attached to orange colored rictus (a part of a bird’s beak). The neck, cuffs, and bottom edge of the parka are trimmed with the fur of an unborn seal and there is the further decoration of duck feathers on the hood and at the shoulders. This parka was collected in the early 1900s by J. H. Maguire, the Superintendent of Schools and Reindeer for the Northwest District of Alaska.

This child’s raincoat is also made of strips of intestine, this time stitched together vertically. The cuffs and bottom of the raincoat are made of fish skin. This was collected in 1898 by F. M. Peironnet who was registered as a physician located in Nome, Alaska on a list of Alaska-Yukon Gold Rush participants.

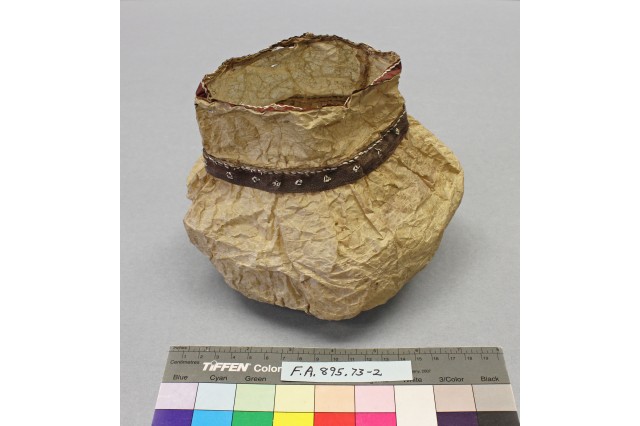

Intestines were also used to make bags that would hold and safeguard other items from the elements. This bag is composed of wide sections of intestine with strips of hide around the top edge and the neck. All of the white stitching and the small decorative details on the band of hide around the neck are done with bird quills.

1 of 1

This rain parka is made of strips of bleached intestine that have been stitched together horizontally. It is decorated at intervals with small brown crested auklet feathers attached to orange colored rictus (a part of a bird’s beak). The neck, cuffs, and bottom edge of the parka are trimmed with the fur of an unborn seal and there is the further decoration of duck feathers on the hood and at the shoulders. This parka was collected in the early 1900s by J. H. Maguire, the Superintendent of Schools and Reindeer for the Northwest District of Alaska.

This child’s raincoat is also made of strips of intestine, this time stitched together vertically. The cuffs and bottom of the raincoat are made of fish skin. This was collected in 1898 by F. M. Peironnet who was registered as a physician located in Nome, Alaska on a list of Alaska-Yukon Gold Rush participants.

Intestines were also used to make bags that would hold and safeguard other items from the elements. This bag is composed of wide sections of intestine with strips of hide around the top edge and the neck. All of the white stitching and the small decorative details on the band of hide around the neck are done with bird quills.

Marine Skin

Another option for waterproof material is more obvious because it already lives underwater. When cleaned and prepared properly, the hides or skins of marine animals will naturally offer the desired level of water-resistance.

Imagine you come from a culture that relies on hunting large marine animals to supply much of the food your community needs to survive. You learn from years of observing and imitating the skills of more experienced hunters that you may only have one chance to hit the animal before it disappears from sight, taking with it the harpoon point you so painstakingly crafted so that its tip would be sharp enough to penetrate the animal’s thick skin. If only there were a way to track the animal once it was hit and prevent it from diving into the sea’s depths where you cannot follow! An inflatable float, attached at the opposite end of a line connected to the harpoon point still lodged in the animal would solve this problem by floating to the surface, thus preventing the animal from diving while also providing the visual marker needed to track the animal's attempted escape.

This float, made from the skin of a seal has an ivory mouthpiece to blow into so that it inflates and floats like a buoy. When not in use, the mouthpiece is stopped with a wooden plug. This was collected on a Museum expedition to study narwhal living off the coast of Greenland in 1976.

Photo by Deniz Durmus

Some of the earliest known examples of clothing made from fish skin come from the Ainu, an ethnic minority living on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido, who traditionally fished for salmon on the open seas. Aside from being lightweight and fairly resistant to tearing, fish skin had several other benefits when used for clothing. When wet, the fish skin swells and tightens seams to reinforce waterproof quality. Fish scales also function as traction when walking across slippery surfaces like snow, ice, or mud.

These shoes were collected in the 1940s by Frank Scolinos who was an assistant prosecutor during the war crimes trial of Hideki Tojo.

1 of 1

Imagine you come from a culture that relies on hunting large marine animals to supply much of the food your community needs to survive. You learn from years of observing and imitating the skills of more experienced hunters that you may only have one chance to hit the animal before it disappears from sight, taking with it the harpoon point you so painstakingly crafted so that its tip would be sharp enough to penetrate the animal’s thick skin. If only there were a way to track the animal once it was hit and prevent it from diving into the sea’s depths where you cannot follow! An inflatable float, attached at the opposite end of a line connected to the harpoon point still lodged in the animal would solve this problem by floating to the surface, thus preventing the animal from diving while also providing the visual marker needed to track the animal's attempted escape.

This float, made from the skin of a seal has an ivory mouthpiece to blow into so that it inflates and floats like a buoy. When not in use, the mouthpiece is stopped with a wooden plug. This was collected on a Museum expedition to study narwhal living off the coast of Greenland in 1976.

Some of the earliest known examples of clothing made from fish skin come from the Ainu, an ethnic minority living on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido, who traditionally fished for salmon on the open seas. Aside from being lightweight and fairly resistant to tearing, fish skin had several other benefits when used for clothing. When wet, the fish skin swells and tightens seams to reinforce waterproof quality. Fish scales also function as traction when walking across slippery surfaces like snow, ice, or mud.

These shoes were collected in the 1940s by Frank Scolinos who was an assistant prosecutor during the war crimes trial of Hideki Tojo.

Photo by Deniz Durmus

Toes & Feet

These examples demonstrate how people will find a use for every part of an animal right down to the toes! Toenails in the form of hooves and claws, toe bones, and even the feet themselves are used to construct a variety of items by a wide range of peoples.

This dance rattle from the early 1900s was made by a member of the Hupa/Hoopa tribe, a group that migrated from the north to settle in a stretch of land along the Trinity River of northwestern California (now called Hoopa Valley). Half portions of deer hooves, more commonly referred to as “deer toes”, are attached at each end of a wand decorated with naturally dyed beargrass woven in a spiraling checkerboard pattern.

Deer toes have long been used by Native American cultures for ornaments and rattles because once deboned, they make a nice hollow bell sound perfect for keeping rhythm with the drum.

This dance rattle from the northwest coast of North America combines the lower pitched sound of the hollow deer toes with the higher clicking sound of thin puffin beaks. The beaks come from the Tufted puffin, the largest type of puffin. Tufted puffins inhabit breeding locations from northwestern Alaska to the central coast California, and winter at sea throughout the North Pacific.

This piece actually includes a variety of interesting animal parts. It is a game similar to a “cup-and-ball” game and is made with a metal pin at one end and perforated deer toes threaded in a line at the other end. There are also tassels of red and yellow dyed porcupine quills and hollowed antelope hooves dangling from the end opposite the metal pin. The objective of the game is to swing the tassels into the air to try to catch as many of the bones and antelope hooves as possible on the metal pin.

This game, or versions like it, were popular with many Native American tribes, particularly among the Plains Indians of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies of North America. This piece comes from the Arapaho/Arapahoe (Hinino'ei) and was collected c. 1875 - 1900 by Edward and Mary Carter who ran a trading post at Fort Bridger, Wyoming, a vital resupply point for wagon trains on the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails.

This necklace from southern Uganda is composed of dik-dik toe bones with red and blue beads in between. Dik-diks are a species of small antelope that live in the bushlands of eastern and southern Africa and were named for the repetitive dik sounds the females make when they feel threatened. This necklace was collected by an NHM staff member in 1970.

Another interesting ornament from Africa comes from the Congo River region in what is now the Central African Republic. This bracelet, collected in the 1890s, is made from the sole of an elephant’s foot. An elephant’s foot is designed so that they actually walk on the tips of their toes and below their foot bones they have a large padded section covered with a very thick epidermal layer that acts as a shock absorber and enables the elephant to walk quietly. This epidermal layer is so thick and dense that it could be carved into durable ornaments like this example though of course, this was done long before the tragic decline in elephant populations due to poaching and habitat destruction.

This tobacco bag from Alaska, c. 1890, is made from the skin and claws of tundra (whistling) swans who breed in the remote Arctic of North America. The maker likely appreciated that this waterfowl's skin is naturally water resistant and would therefore prevent the tobacco from getting wet.

1 of 1

This dance rattle from the early 1900s was made by a member of the Hupa/Hoopa tribe, a group that migrated from the north to settle in a stretch of land along the Trinity River of northwestern California (now called Hoopa Valley). Half portions of deer hooves, more commonly referred to as “deer toes”, are attached at each end of a wand decorated with naturally dyed beargrass woven in a spiraling checkerboard pattern.

Deer toes have long been used by Native American cultures for ornaments and rattles because once deboned, they make a nice hollow bell sound perfect for keeping rhythm with the drum.

This dance rattle from the northwest coast of North America combines the lower pitched sound of the hollow deer toes with the higher clicking sound of thin puffin beaks. The beaks come from the Tufted puffin, the largest type of puffin. Tufted puffins inhabit breeding locations from northwestern Alaska to the central coast California, and winter at sea throughout the North Pacific.

This piece actually includes a variety of interesting animal parts. It is a game similar to a “cup-and-ball” game and is made with a metal pin at one end and perforated deer toes threaded in a line at the other end. There are also tassels of red and yellow dyed porcupine quills and hollowed antelope hooves dangling from the end opposite the metal pin. The objective of the game is to swing the tassels into the air to try to catch as many of the bones and antelope hooves as possible on the metal pin.

This game, or versions like it, were popular with many Native American tribes, particularly among the Plains Indians of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies of North America. This piece comes from the Arapaho/Arapahoe (Hinino'ei) and was collected c. 1875 - 1900 by Edward and Mary Carter who ran a trading post at Fort Bridger, Wyoming, a vital resupply point for wagon trains on the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails.

This necklace from southern Uganda is composed of dik-dik toe bones with red and blue beads in between. Dik-diks are a species of small antelope that live in the bushlands of eastern and southern Africa and were named for the repetitive dik sounds the females make when they feel threatened. This necklace was collected by an NHM staff member in 1970.

Another interesting ornament from Africa comes from the Congo River region in what is now the Central African Republic. This bracelet, collected in the 1890s, is made from the sole of an elephant’s foot. An elephant’s foot is designed so that they actually walk on the tips of their toes and below their foot bones they have a large padded section covered with a very thick epidermal layer that acts as a shock absorber and enables the elephant to walk quietly. This epidermal layer is so thick and dense that it could be carved into durable ornaments like this example though of course, this was done long before the tragic decline in elephant populations due to poaching and habitat destruction.

This tobacco bag from Alaska, c. 1890, is made from the skin and claws of tundra (whistling) swans who breed in the remote Arctic of North America. The maker likely appreciated that this waterfowl's skin is naturally water resistant and would therefore prevent the tobacco from getting wet.

Unusual Fur/Hair

The use of animal fur is common and unfortunately there exists a long history of excessively exploiting the softness and warmth of fur from animals like rabbits, ermines, and foxes for clothing and blankets. However, not all animal fur is soft and it’s not always used for warmth. The following are some fascinating examples where animal fur or hair was used in different ways and for very different reasons.

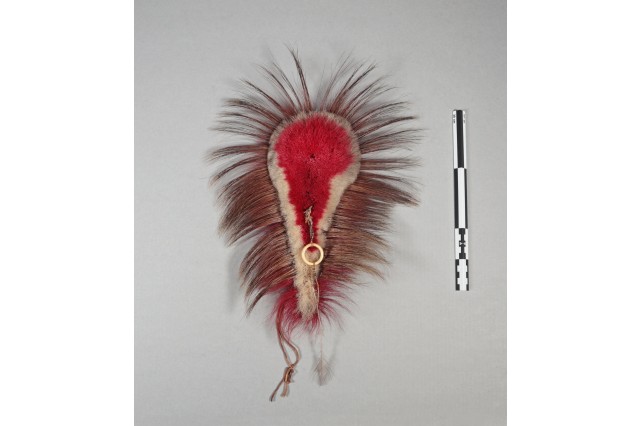

This item is a hair ornament or headdress referred to as a “roach”. These were traditionally worn by male members of a number of Native American tribes east of the Rocky Mountains for combat or at ceremonial events. Today these are still worn by dancers at dances and pow wows where members dress in traditional regalia.

The roach is usually made with stiff porcupine guard hairs that are longer, coarser, and have straighter shafts than other hairs on the porcupine's body. These qualities enable the hair of the roach to stand straight up and to the sides and when worn, they follow along the back of the head like a shortened mane of a horse. The central area of the roach usually includes a shorter kind of hair, in this case deer or mountain goat. The hairs are usually dyed bright colors like red or yellow creating a visually stunning display. This roach was collected in Wyoming in the late 1800s and comes from either the Arapaho/Arapahoe (Hinino’ei) or Shoshone tribes.

It was remarkable to learn that the cord of this delicate girdle is actually composed of hairs from an elephant’s tail! Elephant tail hairs are very thick and a single strand can measure up to 2 ft. long. The hairs have to be softened, boiled and molded into the desired shape while they are still hot. These hairs are strung with white beads interspersed between sections bound with copper wire to form a cord long enough to be worn around the waist.

Ornaments made with elephant hair are actually quite common in the regions that elephants still roam adding to grim list of their parts coveted by traders of illicit goods. In the past, people made these ornaments from the loose hairs they found caught in trees or on the forest floor but after they became associated with good luck and marketed as a trendy tourist souvenir, their demand grew and people began acquiring the hairs using less sustainable methods that threaten elephant livelihoods and encourage a vicious poaching cycle. In 2016 CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) passed a law prohibiting trade of elephant hair but people are still able to legally purchase the stock licensed traders had in their possession before the law came into place. This item was collected in the Central African Republic in the 1890s, long before the need to enforce CITES laws to protect elephant populations.

Another kind of fur/hair not commonly seen in this part of the world is flying fox fur. Flying foxes are actually a kind of megabat that have fox-like faces. They feature in the folk stories of the indigenous groups they’ve co-existed with for millennia in the tropics of Southeast Asia and western Oceania. Among these indigenous cultures, flying fox fur makes a desirable addition to exceptional and/or sacred items.

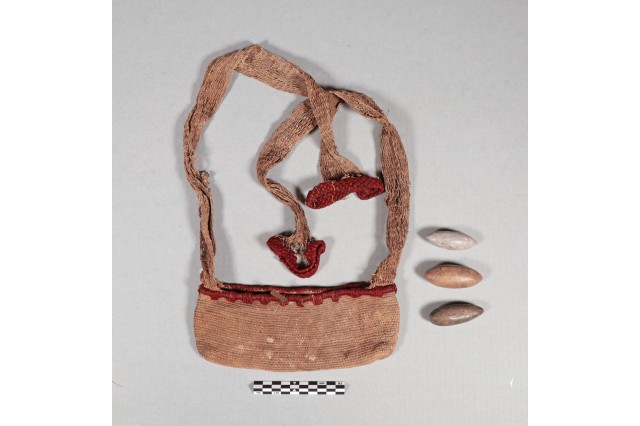

This bag collected from New Caledonia in the 1890s has red flying fox fur woven along the top edge and at the ends of the straps. The bag was used to carry the finely polished slingstones sitting to the side. Warriors of Melanesia were known to use slings and slingstones with deadly accuracy so the use of the flying fox fur indicates the significance these items had to their owner.

1 of 1

This item is a hair ornament or headdress referred to as a “roach”. These were traditionally worn by male members of a number of Native American tribes east of the Rocky Mountains for combat or at ceremonial events. Today these are still worn by dancers at dances and pow wows where members dress in traditional regalia.

The roach is usually made with stiff porcupine guard hairs that are longer, coarser, and have straighter shafts than other hairs on the porcupine's body. These qualities enable the hair of the roach to stand straight up and to the sides and when worn, they follow along the back of the head like a shortened mane of a horse. The central area of the roach usually includes a shorter kind of hair, in this case deer or mountain goat. The hairs are usually dyed bright colors like red or yellow creating a visually stunning display. This roach was collected in Wyoming in the late 1800s and comes from either the Arapaho/Arapahoe (Hinino’ei) or Shoshone tribes.

It was remarkable to learn that the cord of this delicate girdle is actually composed of hairs from an elephant’s tail! Elephant tail hairs are very thick and a single strand can measure up to 2 ft. long. The hairs have to be softened, boiled and molded into the desired shape while they are still hot. These hairs are strung with white beads interspersed between sections bound with copper wire to form a cord long enough to be worn around the waist.

Ornaments made with elephant hair are actually quite common in the regions that elephants still roam adding to grim list of their parts coveted by traders of illicit goods. In the past, people made these ornaments from the loose hairs they found caught in trees or on the forest floor but after they became associated with good luck and marketed as a trendy tourist souvenir, their demand grew and people began acquiring the hairs using less sustainable methods that threaten elephant livelihoods and encourage a vicious poaching cycle. In 2016 CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) passed a law prohibiting trade of elephant hair but people are still able to legally purchase the stock licensed traders had in their possession before the law came into place. This item was collected in the Central African Republic in the 1890s, long before the need to enforce CITES laws to protect elephant populations.

Another kind of fur/hair not commonly seen in this part of the world is flying fox fur. Flying foxes are actually a kind of megabat that have fox-like faces. They feature in the folk stories of the indigenous groups they’ve co-existed with for millennia in the tropics of Southeast Asia and western Oceania. Among these indigenous cultures, flying fox fur makes a desirable addition to exceptional and/or sacred items.

This bag collected from New Caledonia in the 1890s has red flying fox fur woven along the top edge and at the ends of the straps. The bag was used to carry the finely polished slingstones sitting to the side. Warriors of Melanesia were known to use slings and slingstones with deadly accuracy so the use of the flying fox fur indicates the significance these items had to their owner.

Shells & "Shells"

Animals have shells for protection but their shell can also provide a durable material perfect for use as ornaments. The collection has a countless number of items made of, or adorned with shells, but the shells are usually the type found at the beach or removed from mollusks that people eat. The following selection of items includes shells either rarely used or used in extraordinary ways.

At first glance this looks like a necklace made of intricately carved and uniformly polished shells similar to the olivella shell necklaces used as ornament and currency by native coastal Californians for hundreds of years. However, these shells are not the type collected on the coast or even found in water, they are egg shells, specifically ostrich egg shells. Ostrich eggs are the largest of any living bird and their walls are thick enough to be carved without the fear of cracking associated with most egg shells. Evidence of using ostrich eggs as offerings, as containers, and for decoration dates back thousands of years in Africa. This necklace comes from the San peoples, a collective term for multiple indigenous nations that traditionally maintained a semi-nomadic lifestyle. According to the donor, “these necklaces [were] greatly desired by the surrounding Bantu-speaking peoples who acquire them by trade…”

The “shells” used in this item do offer protection but only for part of the animal’s life cycle. This is a leg ornament composed of 43 silk moth cocoons sewn onto a cotton band. Prior to being stitched to the cotton band, the ends of the cocoon were cut off and small pebbles were placed into the hollows to make a sound similar to the sound made by a rattlesnake.

This Tarahumara (Rarámuri) leg ornament was collected in 1982 in Batopilas, Chihuahua, Mexico. Leg ornaments like these are worn by the pascola in certain traditional dances among indigenous tribes of northern Mexico. The pascola performs as a dancer, a host, a speaker, and as comic relief. Pascola attire is particular and these leg ornaments, called tenevoim are worn in long strings wrapped around the dancer’s legs. A pascola dancer demonstrates his skill by the way he makes the leg ornaments rattle.

As mentioned, there are many items in the collection decorated with marine shells but it is rare to find the use of snail shells. This small ornament comes from the Cuna/Kuna peoples of the San Blas archipelago off Panama’s coast. It is composed of multiple delicate shells of a land snail (now known as Labyrinthus uncigerus) native to Guna Yala Comarca, the region of Panama's mainland closest to the San Blas islands. These land snails were likely transported to the islands by people.

This ornament was collected in 1939 by Francis Elmore, an anthropologist from USC. He was aboard the Velero III during the eighth of what would be nine science expeditions funded by Allen Hancock to study the marine environment.

This is another item that puts snail shells to use. This necklace, which initially came to the museum as a loan in 1913, is composed of many large Partula snail shells. Partula snails are also referred to as “Polynesian tree snails” because they were historically distributed across many of the Pacific Islands were they could be found grazing on the decomposing plant material of leaves and trees.

According to this item’s documentation and the label attached to the necklace, this necklace was “worn by the Queen of the Cook Islands.” While it is true that these shells were usually reserved for ceremonial items, it is always best to view comments like these from collectors and donors with some circumspection due to language barriers and the reality of how cultural material is valued and collected. It is well-known among collectors and the people selling or trading the cultural material that items used by “chiefs” or any other type of heightened status are considered more valuable and sometimes the connection to these people of status is exaggerated to increase the item’s value.

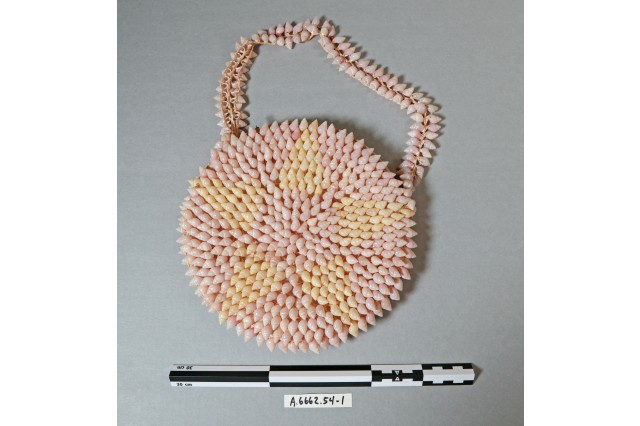

This purse from Guam is also covered in Partula snail shells. It was donated in 1954 before the rapid decline of Partula snail populations to the point that most species of Partula snail are extinct in the wild and only a few survive in captivity. Their near extinction began in 1967 when the French Polynesian government began importing giant African land snails as a human food source. Some of these snails escaped, bred rapidly, and began destroying crops so to control their growing population, they began importing the rosy wolfsnail (Euglandina rosea), also known as the “cannibal snail”, to eat the giant African Land snails. Unfortunately, this carnivorous snail began to prefer to prey on the smaller Partula snail and the biological control program resulted in the catastrophic decline of Partula snail populations.

1 of 1

At first glance this looks like a necklace made of intricately carved and uniformly polished shells similar to the olivella shell necklaces used as ornament and currency by native coastal Californians for hundreds of years. However, these shells are not the type collected on the coast or even found in water, they are egg shells, specifically ostrich egg shells. Ostrich eggs are the largest of any living bird and their walls are thick enough to be carved without the fear of cracking associated with most egg shells. Evidence of using ostrich eggs as offerings, as containers, and for decoration dates back thousands of years in Africa. This necklace comes from the San peoples, a collective term for multiple indigenous nations that traditionally maintained a semi-nomadic lifestyle. According to the donor, “these necklaces [were] greatly desired by the surrounding Bantu-speaking peoples who acquire them by trade…”

The “shells” used in this item do offer protection but only for part of the animal’s life cycle. This is a leg ornament composed of 43 silk moth cocoons sewn onto a cotton band. Prior to being stitched to the cotton band, the ends of the cocoon were cut off and small pebbles were placed into the hollows to make a sound similar to the sound made by a rattlesnake.

This Tarahumara (Rarámuri) leg ornament was collected in 1982 in Batopilas, Chihuahua, Mexico. Leg ornaments like these are worn by the pascola in certain traditional dances among indigenous tribes of northern Mexico. The pascola performs as a dancer, a host, a speaker, and as comic relief. Pascola attire is particular and these leg ornaments, called tenevoim are worn in long strings wrapped around the dancer’s legs. A pascola dancer demonstrates his skill by the way he makes the leg ornaments rattle.

As mentioned, there are many items in the collection decorated with marine shells but it is rare to find the use of snail shells. This small ornament comes from the Cuna/Kuna peoples of the San Blas archipelago off Panama’s coast. It is composed of multiple delicate shells of a land snail (now known as Labyrinthus uncigerus) native to Guna Yala Comarca, the region of Panama's mainland closest to the San Blas islands. These land snails were likely transported to the islands by people.

This ornament was collected in 1939 by Francis Elmore, an anthropologist from USC. He was aboard the Velero III during the eighth of what would be nine science expeditions funded by Allen Hancock to study the marine environment.

This is another item that puts snail shells to use. This necklace, which initially came to the museum as a loan in 1913, is composed of many large Partula snail shells. Partula snails are also referred to as “Polynesian tree snails” because they were historically distributed across many of the Pacific Islands were they could be found grazing on the decomposing plant material of leaves and trees.

According to this item’s documentation and the label attached to the necklace, this necklace was “worn by the Queen of the Cook Islands.” While it is true that these shells were usually reserved for ceremonial items, it is always best to view comments like these from collectors and donors with some circumspection due to language barriers and the reality of how cultural material is valued and collected. It is well-known among collectors and the people selling or trading the cultural material that items used by “chiefs” or any other type of heightened status are considered more valuable and sometimes the connection to these people of status is exaggerated to increase the item’s value.

This purse from Guam is also covered in Partula snail shells. It was donated in 1954 before the rapid decline of Partula snail populations to the point that most species of Partula snail are extinct in the wild and only a few survive in captivity. Their near extinction began in 1967 when the French Polynesian government began importing giant African land snails as a human food source. Some of these snails escaped, bred rapidly, and began destroying crops so to control their growing population, they began importing the rosy wolfsnail (Euglandina rosea), also known as the “cannibal snail”, to eat the giant African Land snails. Unfortunately, this carnivorous snail began to prefer to prey on the smaller Partula snail and the biological control program resulted in the catastrophic decline of Partula snail populations.

Beetles

Lastly we share some unique items that managed to capture the magic of the natural iridescence of certain beetles. Their beauty is so eternal that whether someone decided to use them for an object one hundred years ago or for earrings today (like the ones sold in NHM's gift shop) the result is equally dazzling!

This scarf was collected in Calcutta, India around 1850 and has a design of beetle wings fixed to the textile with thread by way of small holes drilled through the wings. Examples of textiles embroidered with beetle wings can be found on royal garments in India as far back as the Mughal era (16th – 18th centuries) and influenced European clothing of the 1800s. Europe’s desire for these unique textiles led to the rise of a small industry in India that produced the textiles for sale to Europeans during the 19th century.

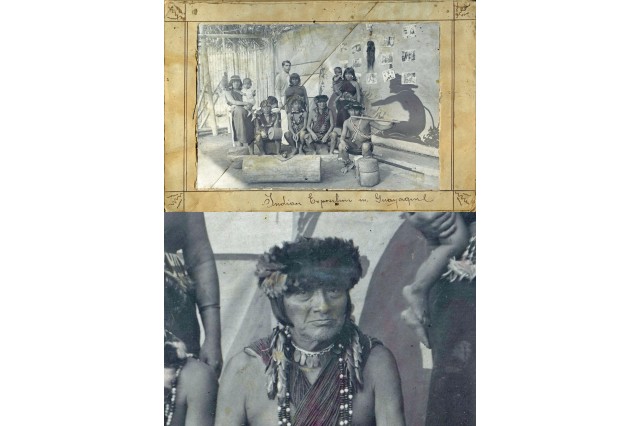

These beetle wing ear ornaments were purchased in Guayaquil, Ecuador in 1938. They are the type of ear ornaments observed to be worn by Shuar (Jivaro) peoples native to the area of the Marañon River and its tributaries in northern Peru and eastern Ecuador. Interestingly, it looks like the wings used in these two sets of ear ornaments come from different beetle families. The ornaments on the left look like Euchroma gigantea, a beetle from the Buprestidae family, also referred to as “jewel beetles” and the one on the right look like Chrysophora chrysochlora, a member of the Scarabaeidae family, also known as scarabs.

For special occasions or ceremonies, the Shuar (Jivaro) elaborately adorn themselves with materials collected from the abundant diversity of their surrounding rainforest. Beetle wings were not only used for decoration but were also perceived as symbols or wealth and power. In this historic photo taken at the Indian Exposition in Guayaquil, c. 1893, the Shuar (Jivaro) patriarch in the center wears the same type of ear ornaments.

This necklace, collected c. 1940, either comes from Australia or New Guinea where several different indigenous groups use iridescent beetles as ornaments even today. There are 25,000 types of beetles found in New Guinea alone and some species of the jewel beetle family are only found in Australia and New Guinea.

Another creature only found in Australia and New Guinea who is also attracted to these colorful beetles is the ever industrious bowerbird. During courtship, the male bowerbird builds an elaborate structure that includes an array of colorful items that he collects. Sometimes he’ll include beetle wing casings, hoping the striking metallic shades will attract a mate. It seems that humans are not the only ones to fully appreciate the glittering beauty of these beetles.

1 of 1

This scarf was collected in Calcutta, India around 1850 and has a design of beetle wings fixed to the textile with thread by way of small holes drilled through the wings. Examples of textiles embroidered with beetle wings can be found on royal garments in India as far back as the Mughal era (16th – 18th centuries) and influenced European clothing of the 1800s. Europe’s desire for these unique textiles led to the rise of a small industry in India that produced the textiles for sale to Europeans during the 19th century.

These beetle wing ear ornaments were purchased in Guayaquil, Ecuador in 1938. They are the type of ear ornaments observed to be worn by Shuar (Jivaro) peoples native to the area of the Marañon River and its tributaries in northern Peru and eastern Ecuador. Interestingly, it looks like the wings used in these two sets of ear ornaments come from different beetle families. The ornaments on the left look like Euchroma gigantea, a beetle from the Buprestidae family, also referred to as “jewel beetles” and the one on the right look like Chrysophora chrysochlora, a member of the Scarabaeidae family, also known as scarabs.

For special occasions or ceremonies, the Shuar (Jivaro) elaborately adorn themselves with materials collected from the abundant diversity of their surrounding rainforest. Beetle wings were not only used for decoration but were also perceived as symbols or wealth and power. In this historic photo taken at the Indian Exposition in Guayaquil, c. 1893, the Shuar (Jivaro) patriarch in the center wears the same type of ear ornaments.

This necklace, collected c. 1940, either comes from Australia or New Guinea where several different indigenous groups use iridescent beetles as ornaments even today. There are 25,000 types of beetles found in New Guinea alone and some species of the jewel beetle family are only found in Australia and New Guinea.

Another creature only found in Australia and New Guinea who is also attracted to these colorful beetles is the ever industrious bowerbird. During courtship, the male bowerbird builds an elaborate structure that includes an array of colorful items that he collects. Sometimes he’ll include beetle wing casings, hoping the striking metallic shades will attract a mate. It seems that humans are not the only ones to fully appreciate the glittering beauty of these beetles.