Unique Plant Fiber Clothing

Across world cultures and throughout the ages, people made and continue to make clothing from plant-based fibers.

Today, the popularity of cotton and linen (made of flax) faces increasing competition from alternatives like bamboo, hemp and soybean with a rising desire to use more environmentally conscious materials.

However, prior to mass production and access to these more commonly known materials, there existed a long tradition of fabricating clothing using other plant options like the inner lining of tree barks or the fibers of palm, pineapple, and banana leaves. Included below is a selection of items from NHM’s Anthropology department that shows the amazing creativity of people using extraordinary skill to create wondrous wardrobes.

Bark Cloth - Tapa

In many regions of the world people have made cloth by collecting strips of the inner lining of bark from certain trees. They would collect this bark, soak it, pound it into thin layers, and then overlap the layers to form a flexible sheet. Among cultures of the Pacific Islands, this bark cloth, usually derived from mulberry trees, takes on the historically and artistically significant name of tapa. Though the cloth is also known by different local names (it is called siapo in Samoa, ngatu in Tonga, and kapa in Hawaii), the word tapa is universally understood throughout the islands. The pounded sheets were decorated by rubbing, stamping, stenciling, dyeing and even smoking, and tapa cloth patterns became family treasures passed down from generation to generation. In the past, before the widespread availability of cotton and other textiles, tapa was the primary source of clothing for Pacific Islanders and was used to both swaddle babies at birth and to wrap the dead for burial. Nowadays, though still worn at special events like weddings, tapa functions more as valuable gift offerings or is prized for its decorative value and used as room dividers or hung on walls as artistic masterpieces.

Full disclosure, while able to provide only a few examples from the Pacific Islands below, NHM has an epic collection of about 350 Polynesian tapas that due to their size (they are often many feet long by many feet wide) and sometimes fragile state, have yet to be suitably showcased. Please stay tuned!

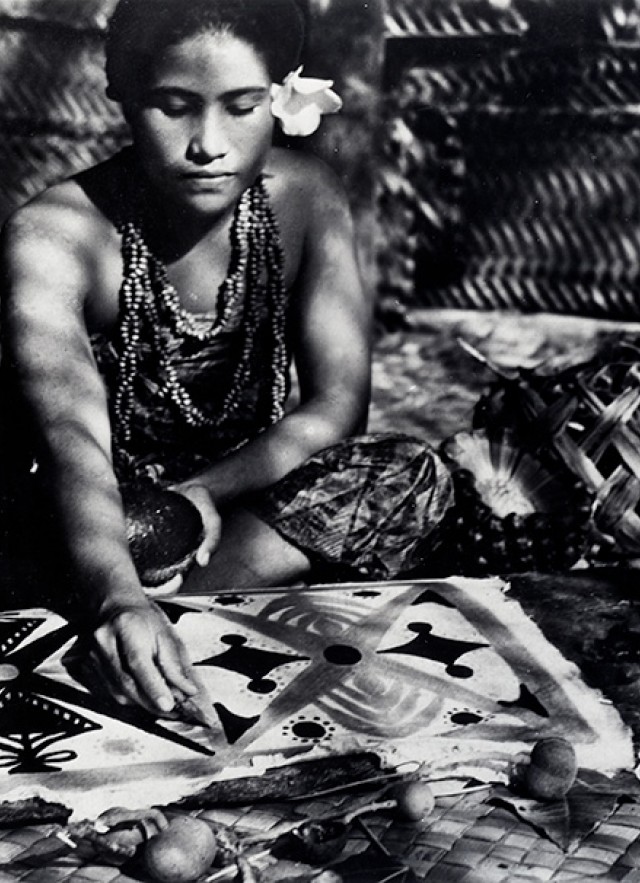

This image shows a tapa from Samoa that was collected in 1909. The traditional fabrication of tapa is labor intensive and when very large, requires the hands of many members of the community.

Bark is stripped and the outer bark is scraped away from the inner lining. Once the inner bark is dried in the sun and then soaked to soften, the pounding and beating can begin. The beaters often have different textures carved on each side to serve different functions in the tapa-making process.

Tapa beaters that have sides with coarse grooves begin the beating process to break down the wet bark and the beater's smoother sides are used towards the end.

Some makers use a side of the beater carved with their own special design at the end of the process to emboss the cloth with a fine texture that will show through on the finished product.

Once the tapa is dried and the edges clipped with shells, the dying and decorating process begins. Many designs were executed using stencils or stamps cut into thin sheets of bamboo. These two bamboo sticks have delicately carved designs at their ends and were used as stamps to repeatedly transfer their patterns to the tapa. They were collected in Hawaii in the early 1900s.

This three-pronged bamboo stick was used as a marker to execute three parallel lines at a time when decorating a tapa. It was collected in Hawaii in the early 1900s.

To decorate larger areas of the tapa, large stamps were made by sewing a design of small sticks or coconut ribs onto a foundation. This tapa stamp from the 1880s comes from Fiji and has coconut fiber sewn onto thick coconut tree bark.

This large area stamp also dating c. 1880, is a siapo stamp from Samoa. Towards the end of the tapa-making process, the maker will go back with a paintbrush to finely tune or accentuate certain areas and/or paint designs freehand.

According to the donor, this was the top of an early 1900s tapa outfit worn by one of “the native dancing girls on the Island of Upolo, Samoan Grp". It still has a wreath of dried flowers attached at the neckline.

This entire dance outfit made of tapa comes from Tahiti and dates to c. 1915.

When visitors from West Papua were in town to receive a Global Conservation Hero award from Conservation International, they visited the storeroom and one recognized this tapa as coming from his home region, stating that the imagery depicts the reflection of fish in the waters of Lake Sentari.

The practice of making bark cloth is not exclusive to the Pacific islands and the Ethnology collection also has mainland examples from several continents. This is a fairly modern bark cloth shirt and mask combination made by a member of the Witoto/Huitoto, an indigenous tribe of the Amazon of northern South America.

The Witoto/Huitoto wear bark cloth masks made from the inner bark of fig trees during dances and festivals. Some dances are purely recreational and are accompanied by games while others are more ceremonial, interpreted as initiation rites or prayers for the health of upcoming harvests. Sometimes the masks are meant to represent ancestors.

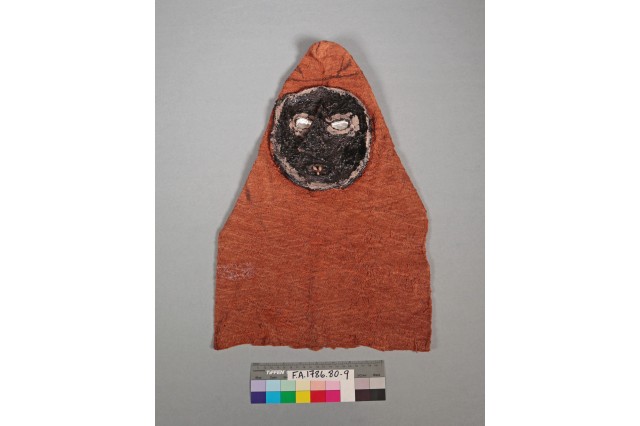

Other tribes of the Amazon also make bark cloth masks. Among the Ticuna/Tucuna/Tikuna of Brazil, the masks are made by and worn by men during elaborate initiation ceremonies for girls. This mask was collected c. 1965.

Bark cloth was not only used for ceremonial activities among the indigenous tribes of the Amazon. Traditionally men wear bark cloth loincloths while women wear bark cloth skirts or aprons. This figure, collected in 1956, shows a person wearing a bark cloth loincloth. It was made by Carajá/Karajá (Iny) natives on Bananal Island, a river island formed from the bisection of the Araguaia River in Brazil.

Another fine bark cloth example in the collection comes from Africa. According to its documentation, this large piece from the early 1900s was a gift to the collector from the King of Bunyoro of Uganda. It is thicker and heavier than the average tapa from the Pacific Islands.

1 of 1

This image shows a tapa from Samoa that was collected in 1909. The traditional fabrication of tapa is labor intensive and when very large, requires the hands of many members of the community.

Bark is stripped and the outer bark is scraped away from the inner lining. Once the inner bark is dried in the sun and then soaked to soften, the pounding and beating can begin. The beaters often have different textures carved on each side to serve different functions in the tapa-making process.

Tapa beaters that have sides with coarse grooves begin the beating process to break down the wet bark and the beater's smoother sides are used towards the end.

Some makers use a side of the beater carved with their own special design at the end of the process to emboss the cloth with a fine texture that will show through on the finished product.

Once the tapa is dried and the edges clipped with shells, the dying and decorating process begins. Many designs were executed using stencils or stamps cut into thin sheets of bamboo. These two bamboo sticks have delicately carved designs at their ends and were used as stamps to repeatedly transfer their patterns to the tapa. They were collected in Hawaii in the early 1900s.

This three-pronged bamboo stick was used as a marker to execute three parallel lines at a time when decorating a tapa. It was collected in Hawaii in the early 1900s.

To decorate larger areas of the tapa, large stamps were made by sewing a design of small sticks or coconut ribs onto a foundation. This tapa stamp from the 1880s comes from Fiji and has coconut fiber sewn onto thick coconut tree bark.

This large area stamp also dating c. 1880, is a siapo stamp from Samoa. Towards the end of the tapa-making process, the maker will go back with a paintbrush to finely tune or accentuate certain areas and/or paint designs freehand.

According to the donor, this was the top of an early 1900s tapa outfit worn by one of “the native dancing girls on the Island of Upolo, Samoan Grp". It still has a wreath of dried flowers attached at the neckline.

This entire dance outfit made of tapa comes from Tahiti and dates to c. 1915.

When visitors from West Papua were in town to receive a Global Conservation Hero award from Conservation International, they visited the storeroom and one recognized this tapa as coming from his home region, stating that the imagery depicts the reflection of fish in the waters of Lake Sentari.

The practice of making bark cloth is not exclusive to the Pacific islands and the Ethnology collection also has mainland examples from several continents. This is a fairly modern bark cloth shirt and mask combination made by a member of the Witoto/Huitoto, an indigenous tribe of the Amazon of northern South America.

The Witoto/Huitoto wear bark cloth masks made from the inner bark of fig trees during dances and festivals. Some dances are purely recreational and are accompanied by games while others are more ceremonial, interpreted as initiation rites or prayers for the health of upcoming harvests. Sometimes the masks are meant to represent ancestors.

Other tribes of the Amazon also make bark cloth masks. Among the Ticuna/Tucuna/Tikuna of Brazil, the masks are made by and worn by men during elaborate initiation ceremonies for girls. This mask was collected c. 1965.

Bark cloth was not only used for ceremonial activities among the indigenous tribes of the Amazon. Traditionally men wear bark cloth loincloths while women wear bark cloth skirts or aprons. This figure, collected in 1956, shows a person wearing a bark cloth loincloth. It was made by Carajá/Karajá (Iny) natives on Bananal Island, a river island formed from the bisection of the Araguaia River in Brazil.

Another fine bark cloth example in the collection comes from Africa. According to its documentation, this large piece from the early 1900s was a gift to the collector from the King of Bunyoro of Uganda. It is thicker and heavier than the average tapa from the Pacific Islands.

Other Bark Cloth - Shredded, Woven, Coiled, and Stitched

Other examples in the collection demonstrate the versatility of tree bark as a clothing material. While pressed bark cloth (tapa) varieties are found all over the globe, so are items that reveal other techniques used to prepare the bark for fabrication.

This bark fiber skirt made by a member of the Mojave/Mohave in the late 1800s is composed of two parts, a shorter section that would hang in the front and a longer one for the back. It was collected by the Coronel family, one of the early, politically important families in Los Angeles when California achieved statehood in 1850.

Clay figurines in the collection offer a glimpse of how these bark fiber skirts may have looked when worn by both men and women of the Mojave/Mohave tribes before the arrival of Europeans.

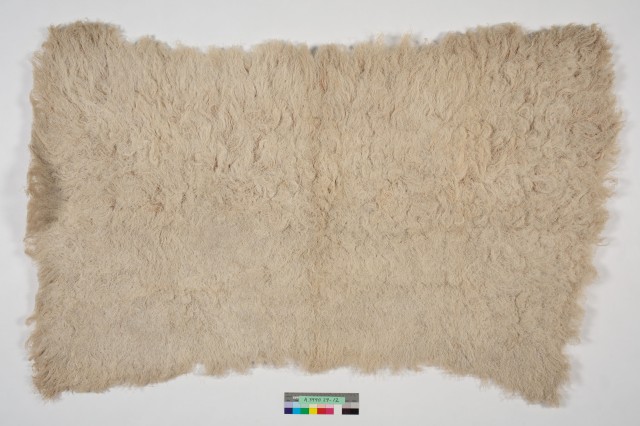

According to the donor’s description, “this beautiful mat is used as a dress and only worn by the ‘great ladies’ of Samoa…It is made from the inner bark of the [Fau] tree. The back has the appearance of woven cloth or burlap the face being rough and shaggy. When fully bleached it has the appearance of a fur robe". The fau tree plays a special role in Samoan mythology as it was said that the gods chose the fau tree to serve as a medium for communication between the spiritual and physical realms.

This apron made of twisted banyan bark was collected in the late 1800s and according to the collector/donor, this kind of dress “now used as money”, was “formerly worn at dances". The long fringe was never unwound to measure its full length since it would be difficult to make such a nicely wound cone again.

It’s interesting to compare the cone of the banyan bark apron to this photo the donor/collector took of a New Caledonian hut and wonder whether the same method of winding was used to form the upper portion of the structure.

This beautifully designed Kuba wrap skirt, c. 1900 has a central design composed of individually stitched triangles of pressed bark. The design has been edged on three sides with wide bands of woven raffia fiber and finished with overstitched embroidery.

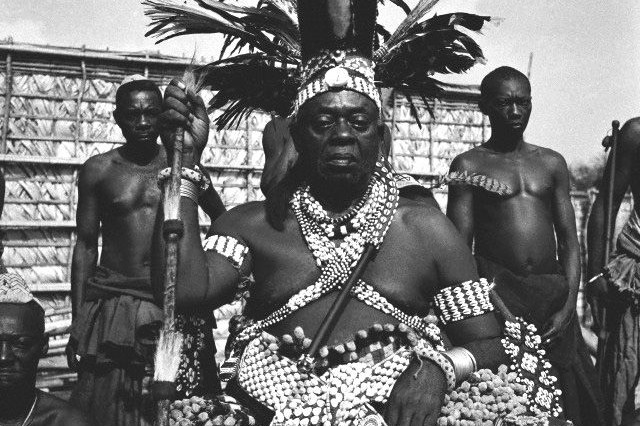

A photo of Nyimi Mbop Mabinshe maMbeky taken by a Corbis photographer in 1950

Between the 17th and early 20th centuries, the Kuba Kingdom was one of Africa’s largest and most powerful societies and renowned for the artistry of its inhabitants, particularly in the crafting of textiles. Intricately patterned textiles were commissioned by royalty and displayed for ceremonial occasions. At that time, the control that the Kuba Kingdom had over the ivory and rubber trades brought an excess of wealth to the Kuba kings and they in turn invested their wealth into their wardrobes. Showcasing their wealth to their subjects helped to further perpetuate the kings' power as competition increased, whether it was with other Kuba kings or with the European colonizers who looked to usurp Kuba control of the rubber market.

1 of 1

This bark fiber skirt made by a member of the Mojave/Mohave in the late 1800s is composed of two parts, a shorter section that would hang in the front and a longer one for the back. It was collected by the Coronel family, one of the early, politically important families in Los Angeles when California achieved statehood in 1850.

Clay figurines in the collection offer a glimpse of how these bark fiber skirts may have looked when worn by both men and women of the Mojave/Mohave tribes before the arrival of Europeans.

According to the donor’s description, “this beautiful mat is used as a dress and only worn by the ‘great ladies’ of Samoa…It is made from the inner bark of the [Fau] tree. The back has the appearance of woven cloth or burlap the face being rough and shaggy. When fully bleached it has the appearance of a fur robe". The fau tree plays a special role in Samoan mythology as it was said that the gods chose the fau tree to serve as a medium for communication between the spiritual and physical realms.

This apron made of twisted banyan bark was collected in the late 1800s and according to the collector/donor, this kind of dress “now used as money”, was “formerly worn at dances". The long fringe was never unwound to measure its full length since it would be difficult to make such a nicely wound cone again.

It’s interesting to compare the cone of the banyan bark apron to this photo the donor/collector took of a New Caledonian hut and wonder whether the same method of winding was used to form the upper portion of the structure.

This beautifully designed Kuba wrap skirt, c. 1900 has a central design composed of individually stitched triangles of pressed bark. The design has been edged on three sides with wide bands of woven raffia fiber and finished with overstitched embroidery.

Between the 17th and early 20th centuries, the Kuba Kingdom was one of Africa’s largest and most powerful societies and renowned for the artistry of its inhabitants, particularly in the crafting of textiles. Intricately patterned textiles were commissioned by royalty and displayed for ceremonial occasions. At that time, the control that the Kuba Kingdom had over the ivory and rubber trades brought an excess of wealth to the Kuba kings and they in turn invested their wealth into their wardrobes. Showcasing their wealth to their subjects helped to further perpetuate the kings' power as competition increased, whether it was with other Kuba kings or with the European colonizers who looked to usurp Kuba control of the rubber market.

A photo of Nyimi Mbop Mabinshe maMbeky taken by a Corbis photographer in 1950

Philippine Jusi Cloth

Extremely delicate and sheer fabric made in the Philippines and used for certain, often celebratory dresses or shirts is called Jusi.

Jusi clothing was originally made of banana leaf fibers or for more precious items to be considered heirloom garments, piña, a more labor intensive fabric made from fibers hand extracted from a special kind of pineapple leaf. Once Chinese mechanically woven silk became more widely available in the 1960s it became the preferred choice and the word “Jusi” became so synonymous with the Chinese silk creations, that Jusi made of banana and pineapple leaf fibers were no longer produced.

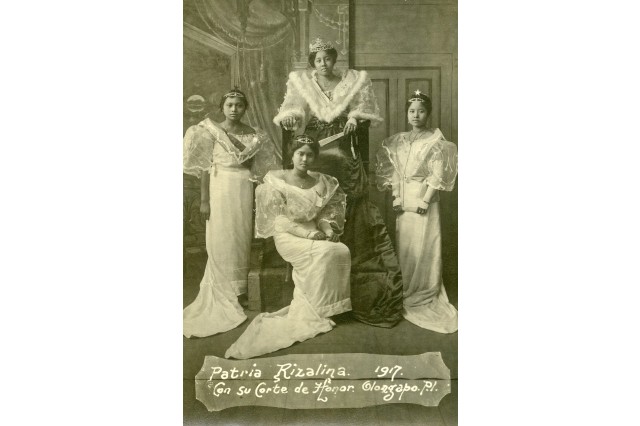

In this historic image from 1917, the ladies are wearing Jusi blouses.

This stunning blouse (c. 1910) made by an Igorot native is composed of a combination of plant fibers. The blouse’s background material consists of delicately woven piña fiber while linen is used for the shadow appliqued decoration. The Igorot ethnic group is a collection of various ethnic groups from the mountains of northern Luzon, Philippines.

This is yet another lovely blouse with full bell sleeves made of woven piña fiber, c. 1918.

This blouse dating somewhere between 1898 and 1902, was made of a rarely used type of laurel locally referred to as makatu. This is not to be mistaken with the Māori word makatu, meaning withchcraft! Manufactured cotton lace was added along the edges of the sleeves.

This piña cloth veil is so finely woven it’s nearly invisible and imagine weaving with invisible thread! According to the item’s documentation, this type of veil was worn by Filipina women when attending Catholic Mass. It was donated to NHM by Miss Amelia Potts Klein, a U.S. Army Nurse who was part of Theodore Roosevelt’s Camp No. 9 during the Spanish American War.

This man’s skirt, locally referred to as a barong tagalong, was made of thinly woven sinamay, a name for fabric woven from processed stalks of the abaca tree. Abaca is a species of banana native to the Philippines often referred to as “Manila hemp”.

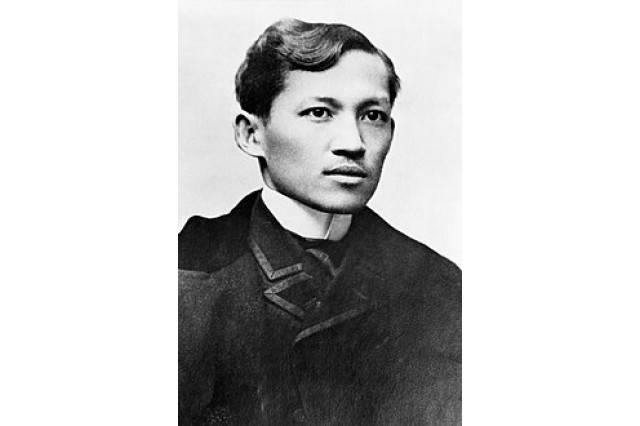

It’s interesting to notice the buttons decorated with a gilded man’s head in relief. According to the item’s documentation, the buttons are “shanked and with rings so that they can be removed for laundering”. The documentation also asks the question as to who the buttons portray stating, “Who? Rizal?”

José Rizal (José Protasio Rizal Mercado y Alonso Realonda) was a national hero to the Filipino people during the Spanish colonial period. He advocated for political reforms which led to his execution by the Spanish colonial government. The Philippine Revolution that eventually led to Philippine Independence was inspired in part by his writings.

1 of 1

In this historic image from 1917, the ladies are wearing Jusi blouses.

This stunning blouse (c. 1910) made by an Igorot native is composed of a combination of plant fibers. The blouse’s background material consists of delicately woven piña fiber while linen is used for the shadow appliqued decoration. The Igorot ethnic group is a collection of various ethnic groups from the mountains of northern Luzon, Philippines.

This is yet another lovely blouse with full bell sleeves made of woven piña fiber, c. 1918.

This blouse dating somewhere between 1898 and 1902, was made of a rarely used type of laurel locally referred to as makatu. This is not to be mistaken with the Māori word makatu, meaning withchcraft! Manufactured cotton lace was added along the edges of the sleeves.

This piña cloth veil is so finely woven it’s nearly invisible and imagine weaving with invisible thread! According to the item’s documentation, this type of veil was worn by Filipina women when attending Catholic Mass. It was donated to NHM by Miss Amelia Potts Klein, a U.S. Army Nurse who was part of Theodore Roosevelt’s Camp No. 9 during the Spanish American War.

This man’s skirt, locally referred to as a barong tagalong, was made of thinly woven sinamay, a name for fabric woven from processed stalks of the abaca tree. Abaca is a species of banana native to the Philippines often referred to as “Manila hemp”.

It’s interesting to notice the buttons decorated with a gilded man’s head in relief. According to the item’s documentation, the buttons are “shanked and with rings so that they can be removed for laundering”. The documentation also asks the question as to who the buttons portray stating, “Who? Rizal?”

José Rizal (José Protasio Rizal Mercado y Alonso Realonda) was a national hero to the Filipino people during the Spanish colonial period. He advocated for political reforms which led to his execution by the Spanish colonial government. The Philippine Revolution that eventually led to Philippine Independence was inspired in part by his writings.

Let's Dance!

Whether for entertainment or for ceremony, dancing is an evolving cultural expression that communicates the history and values of a people through movement. Often particular costumes and accessories are as integral to the routine as the movements themselves. Many of the most interesting plant-based clothing examples in the collection were created for traditional dance rituals practiced in a culture for generations and therefore retain long-established methods of fabrication and use of certain materials.

This Māori piupiu skirt from New Zealand was collected in 1924 and is composed of many individual leaves of the flax plant that hang separately and are only connected by a braided flax band at the top. The process of making a traditional piupiu skirt is labor intensive as sections of the leaves are stripped to the fiber at regular intervals. The leaves are mud dyed and only the exposed fibers take the dye, thus creating the dark sections. When worn during dancing ceremonies the strands sway to and fro and create a soothing, rustling sound.

This shaped dance bodice from Samoa which dates to the 1880s is covered with strips of red and yellow hibiscus fiber. Cotton lines the inside for comfort and stability.

This pandanus (palm) fiber dance skirt is decorated with delicate purple, green, red, yellow, and blue rosettes also made of pandanus and colored using naturally derived dyes. It was collected in the early 1900s at Pago Pago on the island of Tutuila by Robert M. Walker, the first postmaster of American Samoa.

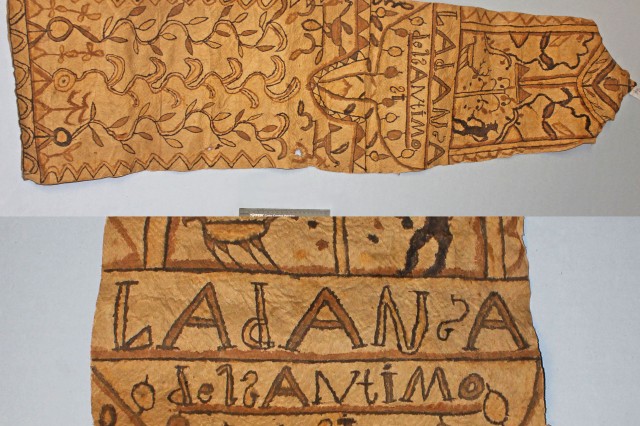

In Panama (as well as other parts of Central and South America), Corpus Christi is celebrated with a series of dances and processions that blend local folklore with the Catholic practices brought to the Americas by Spanish conquistadors. This bark cloth outfit from Colón, Panama would have been worn by a dancer participating in one of the traditional dances.

The outfit also includes a bark cloth flag with the painted words “la dansa del Santimo”, an alternate spelling of la danza del Santisimo and a reference to the "Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament of the Altar", an objective of the Corpus Christi festivities.

Dance of Gallotes or Gallinazos, photo by Iván Alexis Martinez

It is possible that the inclusion of deer antlers and peccary teeth in the outfit's mask were meant to make the mask grotesque and scary to participate as a devil during one of the various dances where the evil devils must eventually surrender and kneel in front of the Eucharist to show submission. However, it is also possible that the drooping antlers were meant to emulate donkey ears making this the outfit for the donkey in the Dance of Gallotes or Gallinazos, another popular Corpus Christi dance that actually originated in Colón.

1 of 1

This Māori piupiu skirt from New Zealand was collected in 1924 and is composed of many individual leaves of the flax plant that hang separately and are only connected by a braided flax band at the top. The process of making a traditional piupiu skirt is labor intensive as sections of the leaves are stripped to the fiber at regular intervals. The leaves are mud dyed and only the exposed fibers take the dye, thus creating the dark sections. When worn during dancing ceremonies the strands sway to and fro and create a soothing, rustling sound.

This shaped dance bodice from Samoa which dates to the 1880s is covered with strips of red and yellow hibiscus fiber. Cotton lines the inside for comfort and stability.

This pandanus (palm) fiber dance skirt is decorated with delicate purple, green, red, yellow, and blue rosettes also made of pandanus and colored using naturally derived dyes. It was collected in the early 1900s at Pago Pago on the island of Tutuila by Robert M. Walker, the first postmaster of American Samoa.

In Panama (as well as other parts of Central and South America), Corpus Christi is celebrated with a series of dances and processions that blend local folklore with the Catholic practices brought to the Americas by Spanish conquistadors. This bark cloth outfit from Colón, Panama would have been worn by a dancer participating in one of the traditional dances.

The outfit also includes a bark cloth flag with the painted words “la dansa del Santimo”, an alternate spelling of la danza del Santisimo and a reference to the "Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament of the Altar", an objective of the Corpus Christi festivities.

It is possible that the inclusion of deer antlers and peccary teeth in the outfit's mask were meant to make the mask grotesque and scary to participate as a devil during one of the various dances where the evil devils must eventually surrender and kneel in front of the Eucharist to show submission. However, it is also possible that the drooping antlers were meant to emulate donkey ears making this the outfit for the donkey in the Dance of Gallotes or Gallinazos, another popular Corpus Christi dance that actually originated in Colón.