BE ADVISED: On Saturday, February 21, the Natural History Museum will be closing at 4 pm. The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum will host the LAFC vs. Inter Miami soccer match, with kickoff at 6:30 pm. This event will impact traffic, parking, and wayfinding in the area due to street closures. Please consider using public transportation or rideshare.

BE ADVISED: The Natural History Museum is not participating in SoCal Museums Free-for-All on Sunday, February 22.

The DIG - March 2021

The DIG - March 2021

Welcome Back to the Dinosaur Institute Gazette!

Dear Friends,

The response to the first edition of our Dinosaur Institute Gazette was overwhelmingly positive! Many thanks to all of you who let me know how much you enjoyed the first of our quarterly updates sharing recent news of the exciting work taking place in the DI. This month, we offer some amazing photos of our featured fossil, Thrinaxodon, as well as pictures from the Grand View site in our “blast from the past.”

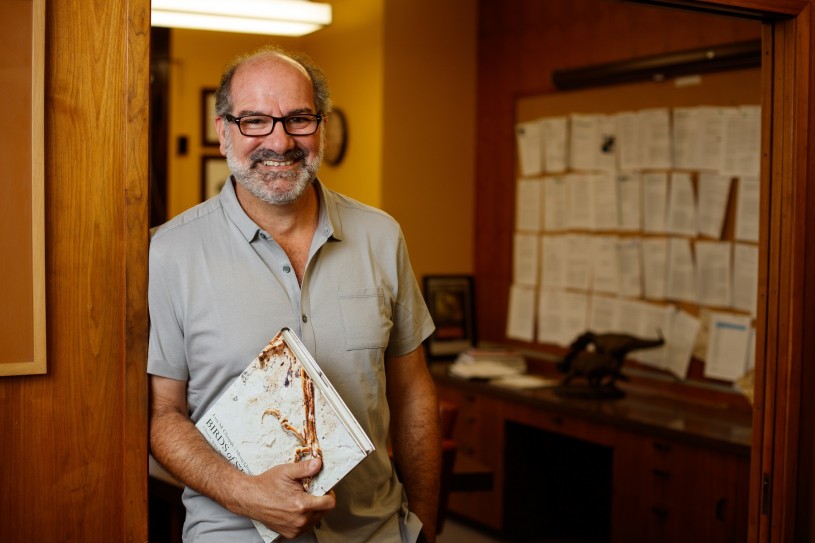

In the first issue, we introduced our graduate students and shared with you how Nate Smith and I have continued to mentor and train these bright minds during the COVID shutdown, readying them to take their place as the next generation of scientists who will conduct the important paleontological work that awaits them. This month in our feature story, we introduce our preparators, who conduct conservation work on our fossils ensuring that they are stabilized to be used for research, exhibition, and permanent storage. I hope you enjoy this edition and look forward to hearing from you soon.

Warm regards,

|

Dr. Luis Chiappe

Senior Vice President, Research and Collections

Gretchen Augustyn Director of the Dinosaur Institute

Meet Our Preparators

The extraordinary team essential to paleontological research in the Dinosaur Institute.

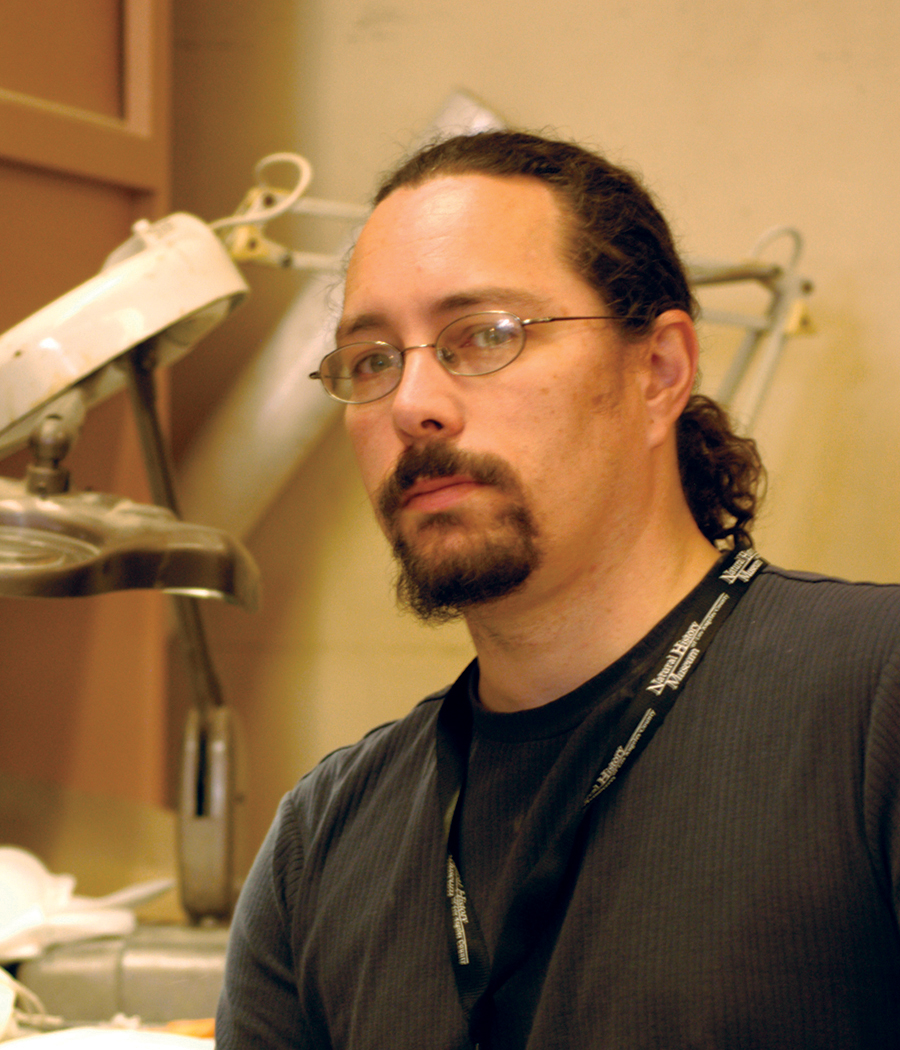

Doug Goodreau

When I'm not preparing ichthyosaurs and sauropods for the Dinosaur institute you can find me applying the same artistic skill sets to other fields. Long before I began working on fossils at NHMLAC in 2000, I was involved with facial reconstruction in the funeral industry as a licensed embalmer, and with the pandemic I'm still quite busy with mortuary work after hours. Along with geology & biology coursework during my undergraduate education, I majored in sculpture, which enables me to recreate highly anatomically detailed features on dinosaurian as well as human remains. One of my lifelong passions is raising exotic reptiles - including crocodilians! I also have a Master's degree in business management that enables me to optimize my seasonal pumpkin carving business: peculiarpumpkinportraits.com (you may have seen me creating some dinosaur designs during our last Haunted Museum event and/or carving with mixed media on Food Network's “Halloween Wars”).

Robert Cripps

I am a Senior Paleontological Preparator working for the Dinosaur Institute here at NHMLAC for over 13 years. Originally from Adelaide, South Australia, I began first as a part time volunteer and joined full time as part of the team working on the new Jane G. Pisano Dinosaur Hall that opened in 2011. I have been involved primarily with the Utah Diplodocus (Gnatalie) specimen and just about everything else that takes place in our busy department. I tend to work most of the time in the Dino Lab which is open for viewing to our visitors, which also allows me to interact with our guests and give informative tours inside the actual lab. When not elbow deep in dinosaurs I enjoy music, art, and holidays in the UK and Europe.

Karl Urhausen

I have long had an interest in history, from the beginnings of the ancient earth to the historical world. While at NHMLAC, I have worked on preparation for many of the specimens displayed in the Jane G. Pisano Dinosaur Hall as well as conservation work in the Becoming Los Angeles Exhibit. As part of the Dinosaur Institute, I have participated in field work in New Mexico, Arizona and Utah. I have spent a lifetime working with my hands applying talents as a sculptor to the fine motor skills required for paleontological preparation. I also have a BFA from California State University Long Beach.

Erika Durazo

I am a Senior Paleontological Preparator that has been working with the Dinosaur Institute for over ten years. I have assisted in field work at various sites including Mexico and Utah. My love of dinosaurs began when I participated in a hands-on Dinosaur Institute internship program called Proyecto Dinosaurios, which was spearheaded by Luis Chiappe. When I’m not preparing fossils, I enjoy tinkering with electronic gadgets and spending time exploring nature with my son.

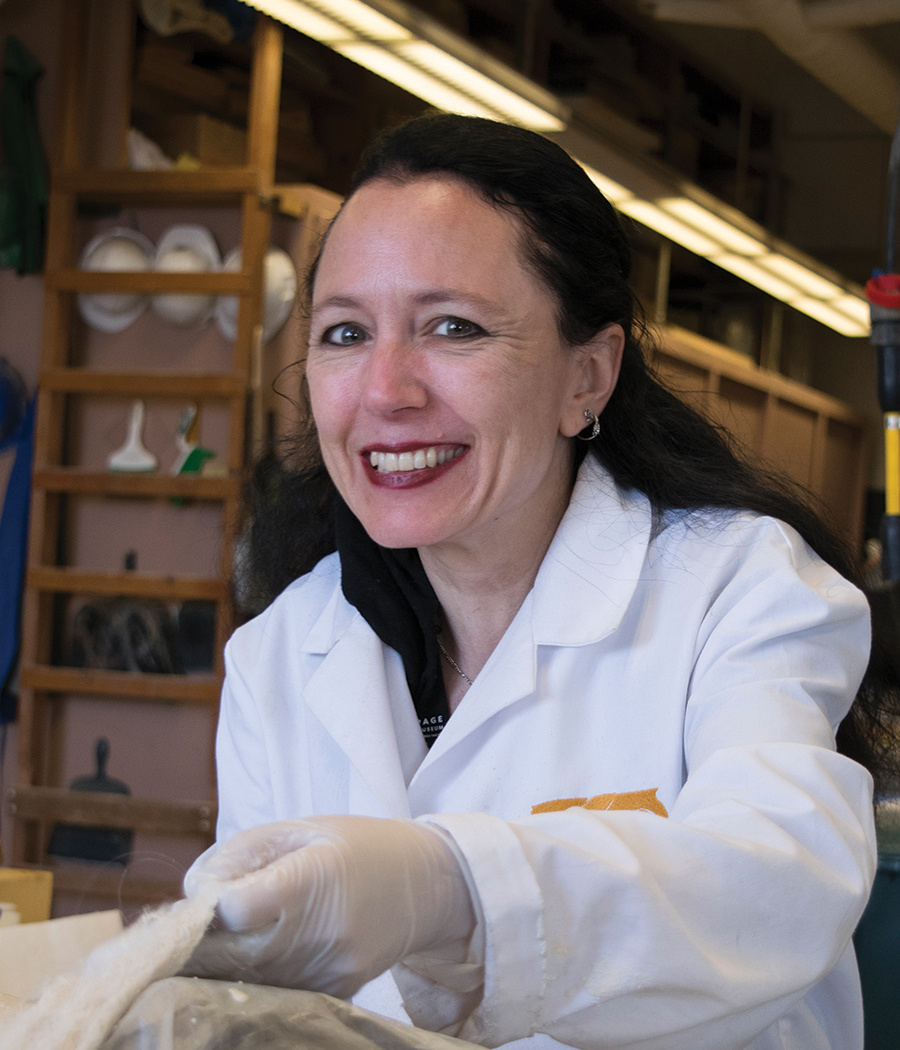

Corinna Bechko

Since earning my Zoology degree I’ve been fortunate to hold several interesting jobs in zoos and wildlife conservation, but I’ve never before worked anywhere as fascinating as NHMLAC. The opportunity to assist in the excavation of a 150 million-year-old Diplodocus from the Gnatalie Quarry in Utah and collaborate in its preparation as it is readied for public display is unforgettable. Over the course of my three years with the Dinosaur Institute I’ve also worked with Triassic marine reptiles, early dinosaurs from New Mexico, and even an exceptional Thrinaxodon (an early mammal relative) collected in Antarctica. When I’m not in the lab I’m usually either rescuing parrots or writing, having recently penned a New York Times best-selling graphic novel as well as co-authoring a book about (what else?) dinosaurs for young readers.

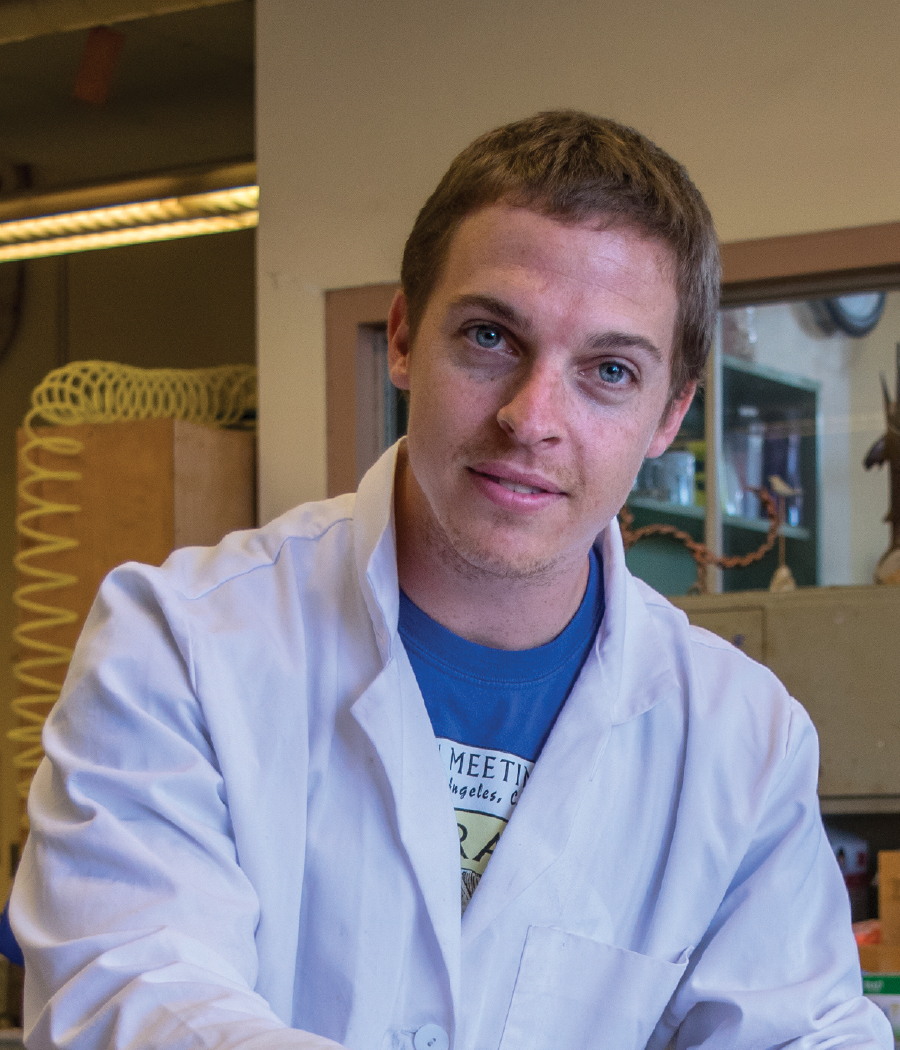

Beau Campbell

I visited NHMLAC and the La Brea Tar Pits as a child being raised in Southern California not knowing one day I would have the opportunity to work at both locations. I started as a volunteer at the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum in 2011 and quickly became a full time preparator in the Fossil Lab, a dream come true. I moved over to the Dinosaur Institute at NHMLAC as a Senior Paleontological Preparator in 2018 and I have had the pleasure of working on Mesozoic fossils from Utah, New Mexico, Nevada and China. I love going out into the field to excavate these amazing fossils, and bring them back to our lab to work on!

Few fossil dinosaurs compare in beauty and completeness to those from the Jehol Biota of northeastern China. Over the last few decades, Luis Chiappe and staff from the Dinosaur Institute have taken countless trips to museums across China to prepare, document, and study dozens of these 131-120 million-year-old scientific treasures, training Chinese students along the way. Protopteryx fengningensis (photo) is a sparrow-sized 131 million-year-old bird and one of the many fossils studied by Luis as part of his research program on early avian evolution (or you may say, late dinosaurian evolution, because birds are avian dinosaurs!). The exquisite plumage of this fossil, including the long ornamental tail feathers identifying it as a male, has allowed Luis and team to recognize that it flew through intermittent flight, a behavior in which flapping alternates with periods where the wings are folded (bound against the body) or spread out (as in gliding). Intermittent flight is an energy-saving strategy common to many small and medium-sized birds living today; Protopteryx, however, represents the earliest bird to have used this flying behavior.

See Photos from Grand View Site, New Mexico

Fieldwork is a fundamental component for building paleontological collections. During the last 20 years, the Dinosaur Institute has maintained an active field program that has significantly contributed to the expansion of the NHMLAC’s collection as well as its research and exhibitions. One of our sites of the last few years is emplaced in the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness of northwestern New Mexico, an area of colorful rocks and towering hoodos located south of the rural town of Farmington. There, our field teams have collected the remains of gigantic titanosaur sauropods along with those of other dinosaurs. At the Grand View site pictured here, our team continues to excavate the 70 million-year-old skeleton of a smaller relative of T. rex, in the process shedding light on an earlier portion of the Tyrant King’s family history.

The Grand View site is on the side of a small hill overlooking the expanse of the Bisti/De Na Zin Wilderness. The quarry at this site, dents the right side of the hill.

Hard rock capping the fossiliferous layer at the Grand View site makes the work extremely arduous, particularly as heavy power tools such as jackhammers are not allowed inside the Wilderness.

With temperatures often hovering over 100ºF, shade is essential for long days of excavating fossils.

The Grand View site has produced the partial skeleton of an early relative of T. rex; here some of their bones are carefully exposed before the journey home, to the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

1 of 1

The Grand View site is on the side of a small hill overlooking the expanse of the Bisti/De Na Zin Wilderness. The quarry at this site, dents the right side of the hill.

Hard rock capping the fossiliferous layer at the Grand View site makes the work extremely arduous, particularly as heavy power tools such as jackhammers are not allowed inside the Wilderness.

With temperatures often hovering over 100ºF, shade is essential for long days of excavating fossils.

The Grand View site has produced the partial skeleton of an early relative of T. rex; here some of their bones are carefully exposed before the journey home, to the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Thrinaxodon Skeleton from the Shackleton Glacier Region of Antarctica

250 million years ago, the earth was just recovering from the greatest mass extinction of all time, and our distant relative, the weasel-sized Thrinaxodon, was scurrying around Antarctica. Discoveries of Thrinaxodon and other mammal relatives in the Early Triassic rocks of Antarctica in the 1970’s provided one of the final lynchpins for the theory of plate tectonics, as these same species were known from other southern continents. During a 2017-18 expedition to the Shackleton Glacier region, Nate Smith collected this skeleton of Thrinaxodon, which is currently being prepared by our Dinosaur Institute preparators, and promises to be the most complete specimen of Thrinaxodon ever recovered from Antarctica.

A view of the Cumulus Hills region looking out toward the Shackleton Glacier, at around 85º South latitude. Early Triassic rocks containing Thrinaxodon and other vertebrate fossils are the lighter brown patches off the tip and to the left of the large ice tongue in the foreground.

Nate Smith and his expedition team were ferried from basecamp to rock outcrops in the Shackleton Glacier region with helicopters, like the one seen here dropping off paleontologists at an area known as Halfmoon Bluff.

An articulated vertebral column of Thrinaxodon was discovered by Nate Smith during the 2017-18 expedition, weathering out of the coarse sandstones at Halfmoon Bluff.

Now back at the NHMLAC, expert preparation reveals the complete skeleton and skull of the Thrinaxodon fossil. This specimen represents the most complete Thrinaxodon fossil ever recovered from Antarctica, and promises to yield new insight into the evolution and biology of our distant mammal-relatives that lived in polar regions during the Early Triassic.

1 of 1

A view of the Cumulus Hills region looking out toward the Shackleton Glacier, at around 85º South latitude. Early Triassic rocks containing Thrinaxodon and other vertebrate fossils are the lighter brown patches off the tip and to the left of the large ice tongue in the foreground.

Nate Smith and his expedition team were ferried from basecamp to rock outcrops in the Shackleton Glacier region with helicopters, like the one seen here dropping off paleontologists at an area known as Halfmoon Bluff.

An articulated vertebral column of Thrinaxodon was discovered by Nate Smith during the 2017-18 expedition, weathering out of the coarse sandstones at Halfmoon Bluff.

Now back at the NHMLAC, expert preparation reveals the complete skeleton and skull of the Thrinaxodon fossil. This specimen represents the most complete Thrinaxodon fossil ever recovered from Antarctica, and promises to yield new insight into the evolution and biology of our distant mammal-relatives that lived in polar regions during the Early Triassic.

Thank you for supporting the Dinosaur Institute