Los Angeles, (June 17, 2025)—A newly discovered raccoon-sized armored monstersaurian lizard from Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in southern Utah unearths a surprising diversity of these very big lizards at the pinnacle of the Age of Dinosaurs. Named for the goblin prince from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, the new species Bolg amondol also illuminates the sometimes murky path that life traveled between ancient continents. Published in the open-access journal Royal Society Open Science, the collaborative research led by the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County’s Dinosaur Institute reveals hidden treasures awaiting future paleontologists in the bowels of museum fossil collections, and the vast potential of paleontological heritage preserved in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and other public lands.

“I opened this jar of bones labeled ‘lizard’ at the Natural History Museum of Utah, and was like, oh wow, there's a fragmentary skeleton here,” says lead author Dr. Hank Woolley from the Dinosaur Institute. “We know very little about large-bodied lizards from the Kaiparowits Formation in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah, so I knew this was significant right away.”

A Moniker from Middle-earth

Bolg represents an evolutionary lineage that sprouted within a group of large-bodied lizards called monstersaurs, the most familiar example being the Gila monsters, which still roam the deserts where Bolg was recovered from. Woolley knew that a new species of monstersaur called for an appropriate name from an iconic monster creator: J.R.R. Tolkien. “Bolg is a great sounding name. It's a goblin prince from The Hobbit, and I think of these lizards as goblin-like, especially looking at their skulls,” says Woolley. He used the fictional language Sindarin—created by Tolkien for his elves—to craft the species epithet. “Amon” means “mound”, and “dol” means “head” in the Elvish language, a reference to the mound-like osteoderms found on Bolg’s and other monstersaur skulls. “Mound-Headed Bolg” would fit right in with the goblins—and it’s revealing quite a bit about monstersaurs.”

Hidden Gems in Collection Drawers

Bolg is a great example of the importance of natural history museum collections,” says co-author Dr. Randy Irmis from the University of Utah. “Although we knew the specimen was significant when it was discovered back in 2006, it took a specialist in lizard evolution like Hank to truly recognize its scientific importance, and take on the task of researching and scientifically describing this new species.”

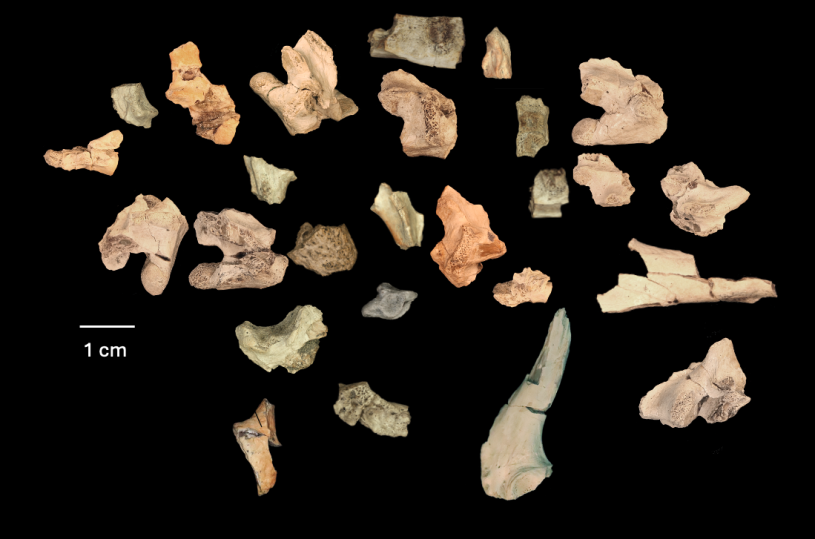

The new species was identified from an associated skeleton of fragmentary bones: tiny pieces of the skull, vertebrae, girdles, limbs, and the bony armor called osteoderms.

“What's really interesting about this holotype specimen of Bolg is that it's fragmentary, yes, but we have a broad sample of the skeleton preserved,” Woolley says. “There's no overlapping bones— there's not two left hip bones or anything like that. So we can be confident that these remains likely belonged to a single individual.”

Most of the fossil lizards from the Age of Dinosaurs are even more fragmented—often just single isolated bones or teeth—so despite their fragmentary nature, the parts of Bolg’s skeleton that survived contain a stunning amount of information.

“That means more characteristics are available for us to assess and compare to similar-looking lizards. Importantly, we can use those characteristics to understand this animal's evolutionary relationships and test hypotheses about where it fits on the lizard tree of life,” says Woolley.

Stairway to Monstersaurs

The Monstersauria are characterized by their large size and distinctive features like pitted, polygonal armor attached to their skulls and sharp, spire-like teeth. They have a roughly 100 million-year history, but their fossil record is largely incomplete, making the discovery of Bolg a big deal for understanding these charismatic lizards, and Bolg would have been a bit of a monster to our eyes.

“Three feet tip to tail, maybe even bigger than that, depending on the length of the tail and torso,” says Woolley. “So by modern lizard standards, a very large animal, similar in size to a Savannah monitor lizard; something that you wouldn’t want to mess around with.”

The identification of a new species of monstersaur highlights the likelihood that there were many more kinds of big lizards in the Late Cretaceous. Additionally, this finding shows that unexplored diversity is waiting to be dug up in the field and in paleontology collections.

Bolg’s closest known relative hails from the other side of the planet in the Gobi Desert of Asia. While dinosaurs have long been known to have traveled between the once connected continents during the Late Cretaceous Period, the discovery of Bolg reveals that smaller animals also made the trek, suggesting there were common patterns of biogeography across terrestrial vertebrates during this time.

Dr. Woolley began this research as a PhD student at the Dinosaur Institute and has continued it as a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow in the department, underscoring the value of funding scientific research and the unique role the Dinosaur Institute plays as a source of mentorship for young paleontologists.

“The Natural History Museum and Dinosaur Institute has been proud to lead the way in empowering early career scientists,” says Dr. Nathan Smith, co-author and Gretchen Augustyn Director & Curator of the Dinosaur Institute. In addition to Dr. Woolley, co-author Dr. Keegan Melstrom (now an Assistant Professor at the University of Central Oklahoma), was also a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Dinosaur Institute. “The result of that investment and continued growth of programs like the Dinosaur Institute Fellowship Fund is groundbreaking paleontological research and new discoveries that highlight the value of museum collections and expand our knowledge of Earth history.”

Field collection of the specimens described in this study was conducted under paleontological permits issued by the Bureau of Land Management. This study was funded by the Bureau of Land Management, National Science Foundation award 2205564, the NHMLAC Dinosaur Institute, and the University of Utah.

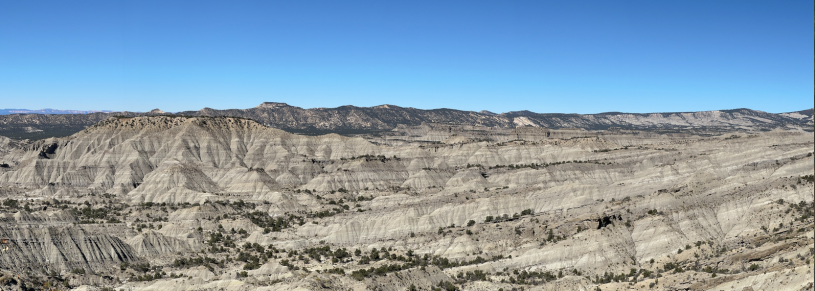

The rocks where Bolg was discovered, the Kaiparowits Formation of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, have emerged as a paleontological hotspot over the past 25 years, producing one of the most astounding dinosaur-dominated records anywhere in North America with dozens of new species and critical insights into the past. Discoveries like this underscore the importance of protecting public lands in the western USA for science and research.

MEDIA CONTACTS:

Tyler Hayden

Science Communications Specialist

thayden@nhm.org

Amy Hood

Director of Communications

ahood@nhm.org