Spiky, Hairy, Shiny: Insects of L.A.

If we want to understand how our decisions shape the world around us, we can start by simply paying attention to what insects are doing in our own neighborhoods.

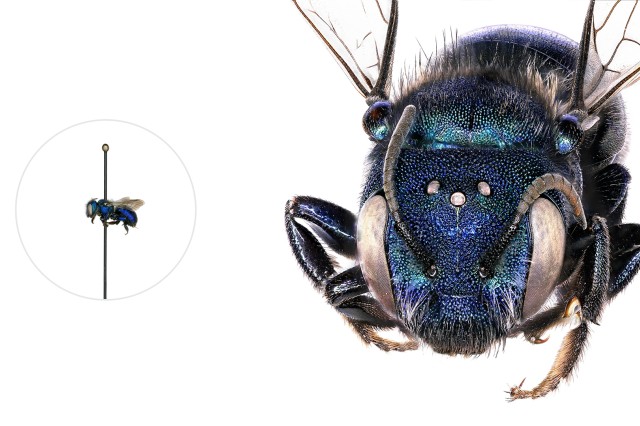

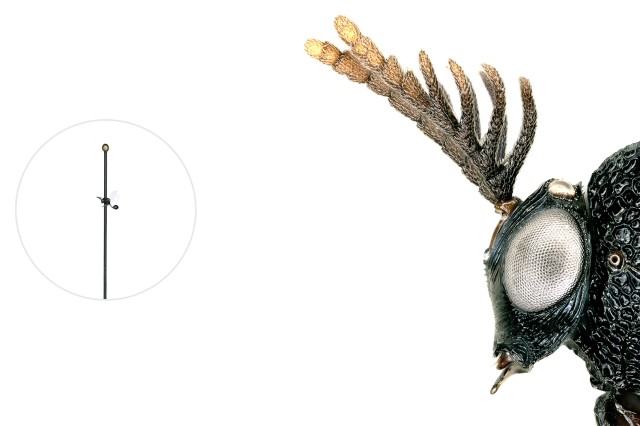

On any given day in L.A., count on running into thousands of insects, many of which are barely visible. Since 2012, volunteers and Museum scientists have been collecting and photographing samples of this diversity as part of the BioSCAN (Biodiversity Science: City and Nature) project—in the process documenting environmental change over time. Spiky, Hairy, Shiny, an online exhibition, zooms in on this hidden world: come meet these six-legged Angelenos and let their beauty surprise and delight!

Soothing Sounds

When you have a quiet moment, put on your headphones and be transported via the sounds of Los Angeles insects, from dawn to dusk.

BioSCAN: The World's Largest Urban Biodiversity Study

What makes BioSCAN the biggest survey of its kind? First of all, the number of insect traps (80) placed by Museum staff and volunteers. Second, the urban setting: the BioSCAN project is discovering new species and examining insect distributions in the core of the Los Angeles Basin and out to the coast, mountains, and nearby deserts. Through biodiversity studies like these, scientists can track which species are in an area and how common they are. To date, we have identified 800 species, including 47 species new to science. For more results, see here.

Finding Insects in Your Neighborhood

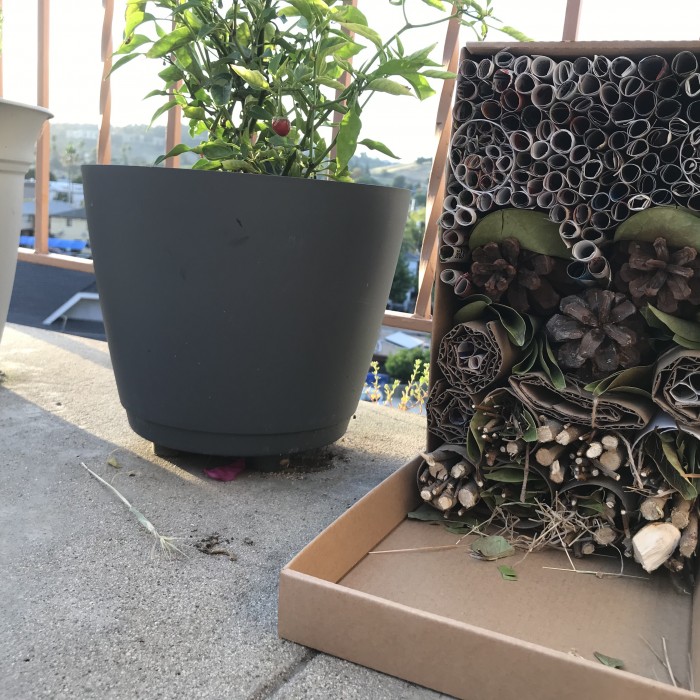

No matter where you live in Los Angeles, you can find—and support—native insect communities. Roll over a few of our BioSCAN collection sites on the map below to see examples.

More on Bugs

Activities

Here are some things you can do at home (or just about anywhere) to observe and learn more about the insects around you.

Acknowledgements

The BioSCAN project was made possible in part through the generous support of Esther S.M. Chui-Chao and The Seaver Institute. The project also would not have happened without the collaboration of our BioSCAN site hosts, who provided access to their yards, community gardens, local green spaces, and schools. We are grateful for their cooperation and dedication.