Bugs For Life

NHM researchers’ ambitious plan to DNA barcode every insect species in CA—before it’s too late

Published May 5, 2023

Whether they’re fluttering, buzzing, or crawling, insects all over the planet are vanishing in the wake of human development, pesticides, and climate change, ushering in what’s been called the Insect Apocalypse—the rapid, worldwide decline in both the amount and diversity of insects. Estimates are hard to pin down, but researchers think we may have already lost 70 percent of insect biomass since the 1970s.

Researchers like Dr. Brian Brown, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County’s Curator of Entomology, have already shown the incredible diversity of insect life waiting to be discovered through projects like BioSCAN, an in-depth look at insect biodiversity in urban Los Angeles. Brown and other scientists secured six million dollars in grant funding to expand their search into the California Insect Barcoding Initiative (CIBI). NHM researchers and their collaborators have set their sights on documenting California’s insect biodiversity before it’s too late by barcoding every species of insect in the state.

“The goal of the project is to collect every insect species in the state of California, which is a huge huge goal,” says Dr. Austin Baker, the post-doctoral fellow leading NHM’s CIBI efforts. Along with NHM, institutions including the California Department of Food and Agriculture, UC Berkeley, UC Riverside, San Diego Natural History Museum, and the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco are all working together to cover as much ground as possible. “So to meet that, we're also supplementing these new collections by sampling tissue from our existing collections and our museum from material that's been identified to species and from California.”

To really understand how gigantic an undertaking this is, it might help to understand just how big a task Baker and his fellow researchers have set for themselves—the estimated number of insect species in California is 30,000–35,000 or even more, and again, BioSCAN found 30 undescribed species in L.A. alone.

Still, if you’re currently scratching a mosquito bite, you might be wondering what the big deal is. Insects are the oil that greases the larger ecosystem through things like pollinating plants and replenishing the soil. You could say they’re also the largest part of the ecosystem since insects make up about half of all the biomass of animal life on the planet. "The number of insects dwarfs any other group of animals, plants, or anything else," says Baker. "So if you really want to understand the effects of environmental change on biodiversity loss and extinction events, insects are the group that you want to study.”

“What we're noticing with the research the ‘insect apocalypse’ is based on, it's not just the numbers themselves declining,” says Baker. “When you get a huge loss of biomass, you would have to assume the biodiversity is being lost as well. The number of insects dwarfs any other group of animals, plants, or anything else. So if you really want to understand the effects of environmental change on biodiversity loss and extinction events, insects are the group that you want to study.”

“When you start losing a few species, it'll mostly go unnoticed by most people unless they're interested in finding those things,” says Baker. “But as this escalates and snowballs, the loss of some species will lead to the loss of more species. Eventually, your average layperson is going to notice. Oh, where did all the monarchs go? Where did all the painted ladies go? The more charismatic things will eventually disappear as well.”

That mosquito feeding on you? Something else is feeding on it. Bees famously pollinate our plants, both food crops and wild, but some pollinators may only pollinate an individual plant species. The richness of insect life keeps larger animals like birds, insects, and mammals fed, and declines in insect populations have led to declines in birds, even the absence of entire species that were abundant until recently. The threads of the food web can be so thin, and it’s impossible to say what happens when one thread is completely severed.

“The number of insects dwarfs any other group of animals, plants, or anything else. So if you really want to understand the effects of environmental change on biodiversity loss and extinction events, insects are the group that you want to study.” Austin Baker

Bug Check on Aisle 9

If you’re picturing somebody very carefully attaching a barcode to say, an ant, rest assured that’s not what we mean by DNA barcoding. Insects are collected in the field and sent out to a lab where chemicals are applied to the samples that break down the insect cells until only the DNA is left. The CIBI project researchers will connect specific sequences of DNA to their representative insect species, building a digital library of unique codes that researchers can then easily compare DNA to that library to identify a known insect species or determine if it’s something entirely unknown to science.

Identifying an insect can be difficult and time-consuming, even for someone with extensive training. In the case of an extremely rare insect, it can be pretty impossible. The larval stage of an insect might be completely unknown and look totally different from the adult fly or beetle. Future researchers will be able to scan those barcodes to identify species by their DNA.

For scientists, this library will be an invaluable tool. Comparing barcode data to museum collections, for example, can help us understand how species’ ranges have changed over time, helping identify habitats that need protecting or other knock-on ecological damage. It could even help identify the stomach contents of other animals to see how their diets are changing. With our increasingly erratic and fast-changing climate, understanding those changes quickly and at scale could be invaluable to protecting California’s environment in the smartest ways possible.

“If we really want to conserve species, we should be finding areas of insect biodiversity to prioritize conserving,” Baker says. “The unknowns are really hard to predict but that's one of my major focuses— going out there finding the spots that I think there’s going to be the most biodiversity.”

The same climate and geographic features that attract people to California make its smaller residents more difficult to keep track of. It might be the only state in the U.S. where you can start the day surfing, go for a desert hike in the afternoon, and end it on the slopes—and each of those stops has insect species specific to its own environment which could be as localized as a specific dried up pond—the dried up pond down the corner might have an entirely different insect playing the same role, and the pond two ponds over a different one altogether.

“California is this interesting place on the coast with the mountains and the desert—you just have every different type of ecosystem.”

“The unknowns are really hard to predict but that's one of my major focuses— going out there finding the spots that I think there’s going to be the most biodiversity.” Austin Baker

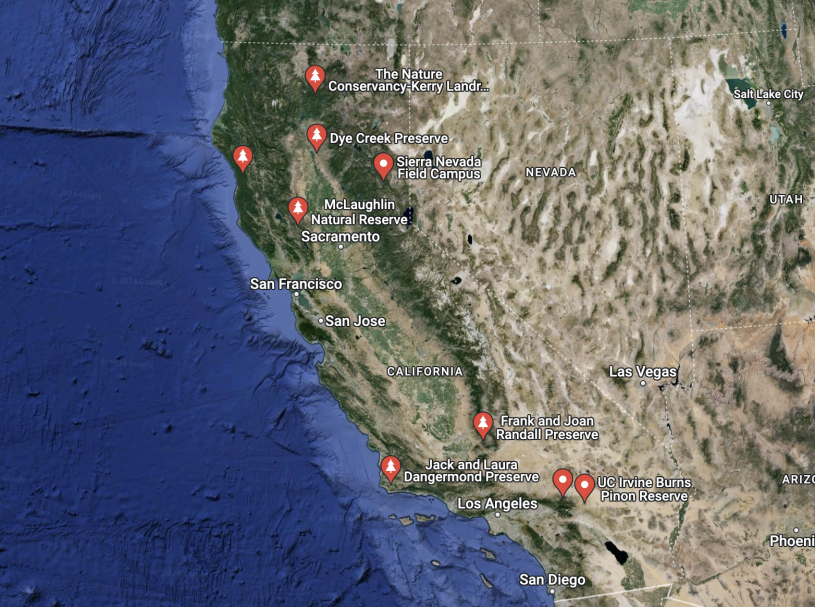

To capture the most representative samples and the diverse landscapes of the state, Baker and researchers from the other participating institutions are focusing on California state parks. “The side that I'm mostly working on is the new collections where we're going out trying to find fresh material and in particular trying to find the species that we don't even know or are out there yet and so it's pretty hard to target something if you don't know that it even exists.”

“So we are trying to find spots that we would assume would have different biodiversity than other spots. So my approach, this whole thing has been looking at how the EPA has defined the ecoregions across California and sampling every ecoregion that we can to equitably cover as much land area and habitat diversity as possible.”

Ecoregions are places that have similar ecosystems to other areas. Think of it as a way to classify a place by its landscape features, local climate, and the types of life inhabiting it. The four major ecoregions in California are coast ranges (like Redwoods National Park), deserts (like the Mojave), forested mountains (like the Sierra Nevada), and Mediterranean (like the Central Valley). Some of those can be further divided into more specific types–forested mountains, for example, includes the Sierra Nevada, the Eastern Cascades Slopes and Foothills, and the Klamath Mountains. Working from the NHM Entomology Collections and in the field, Collections Manager Giar-Ann Kung is also deeply involved with the project, managing the intensely collaborative workload as well as setting up a number of observation sites.

With minimal human impact, the state parks are perfect for sampling insects from all the diverse landscapes of California while highlighting the value of those wild spaces for protecting our biodiversity. Knowing more about what’s buzzing around the parks increases their value as likely homes to unique wildlife, with the chance to garner more publicity for these protected areas—it’s a win, win, win for wildlife. The more we know, the more we know how valuable it is to protect and expand our wild areas. Benefiting state parks is only part of the virtuous cycle spinning out from the CIBI project.

Baker emphasizes that sequencing the DNA of the insects they’ve collected has only just begun, but those early returns are already raising exciting questions. Only one species was found throughout the seven samples from across the state, the phorid fly pictured above.

“What adaptation gives this one species the ability to cover the entire state? High altitude, low altitude, dune system, beach system, pine—how is one species surviving and all of these different things,” asks Baker. “Finding out that there is something out there that's widespread when most other species aren’t is an exciting discovery.”

Analyzing the collected specimens has only just begun. It’s difficult to guarantee there will be any number of new species described, but BioSCAN initially began on a bet that Brown could find a new species in a trustee’s West L.A. backyard–CIBI researchers are covering the state of California, and on top of whatever new species they might find, there’s a treasure trove of data coming along with all those insects.

“Our primary goal is biodiversity and our secondary goal is distributional information, so it's okay if we sequence the same species for multiple localities because it helps build our ecological knowledge of where that species could exist,” says Baker. “We can then develop distributional maps and other resources people could use for things like conservation or assessing where you can find the species in future attempts to study them.”

The maps and other data CIBI generates will help policymakers and researchers better understand how to protect California’s biodiversity and help conservationists and scientists better understand the forces behind the Insect Apocalypse, but the great thing about such a large set of new data is that there will certainly be other beneficial uses we can’t predict. Better data make better-informed decisions and new science possible, even if we can’t know exactly how in the present.

Image by Kelsey Bailey

When Baker, Kung, and Brown’s predecessors collected insects for NHM over a hundred years ago, they never thought that museum specimens might become sources for DNA sequencing—the science didn’t exist.

“There's just an overwhelming amount of diversity of the little tiny things out there that are just unknown to science,” says Baker. “So it's really exciting to do a project like this where we can draw attention to them and say, ‘Hey, this thing is potentially new and interesting, you know?’” Where there’s discovery, there is hope, even in the face of an “apocalypse”.