BE ADVISED: The Natural History Museum is not participating in SoCal Museums Free-for-All on Sunday, February 22.

Dakota Gets a Makeover

See how our Performing Arts staff refurbished the Museum's life-size Triceratops puppet for her starring role in the all-new Dino Encounters show.

Published December 22, 2022

Dakota, our life-size adolescent Triceratops suit puppet and star of the revamped Dinosaur Encounters show, feels like a brand-new dino now thanks to her in-house entourage who spiffed up the Late Cretaceous showstopper.

Erth, the Australian puppet-making company that birthed the big-headed, three-horned darling in 2007, certainly built a sturdy performer. But after hundreds of hours mesmerizing audiences since then, the puppet’s outsides were frayed and stretched and the inner workings, like a jiggly jalopy, became challenging to operate. So this year, a crew of staffers in the Museum’s Performing Arts program, each of whom possess formidable technical skills, restored the 9-foot-long, 4-foot-tall celebrity in time for the new show’s debut.

Dinosaur Encounters ushers audience members back 66 million years, into the Age of Dinosaurs, for a day in the life of this Triceratops heroine. In eight performances a week in the North American Mammal Hall, visitors listen to an ambient soundscape and witness the seven-year-old herbivore confronting challenges, from thunderstorms to large, bothersome insects to encounters with a certain young T. rex.

When it comes to bringing collections to life and forming empathetic connections with visitors, few tools are as powerful as live theater. “It's like walking into a living diorama, but it really is more than that because the audience is part of it as well,” says Emily Franz, a theatrical technician and lead fabricator, part of the core maintenance crew. “The audience really is participating in moments. Our performances are that beautiful marriage of art and science and education all wrapped up into one and you really feel like you're in it, which is so cool."

The show begins with a magic shadow puppetry performance that foreshadows the live-action drama.

1 of 1

The show begins with a magic shadow puppetry performance that foreshadows the live-action drama.

Heavy Is the Crown

It took five months to design, redesign, source, and test new materials for such technically intricate machinery. A guiding principle of the overhaul was to make the puppet more puppeteer-friendly. Triceratops, when it roamed Earth, had the biggest skull of any land animal, weighing in at about 1.5 tons (think the poundage of two pandas). Dakota also carries a good bit of her 65-pound heft in her noggin. To relieve the heaviness, the crew re-sculpted the foam to create a pocket for the puppeteer's head, and replaced worn and stretched-out bungees that hold the entire neck piece up, which allowed it to still maneuver, but relieved some of the pressure.

“It's so much more comfortable. There's a freedom with greater range of movement,” said Betsy Zajko, a quadruped puppeteer and technical coordinator who repairs and maintains the creatures. That flexibility is key, considering that the puppeteer operator’s frame is firmly attached. To operate Dakota, Zajko wears a backpack-type strap across her chest, hips, and legs—like a parachutist's harness.

Other ergonomic improvements included redesigning and replacing the arms, and installing comfy crutches with rubber bottoms. Erth was consulted for the crutch replacement and sent over new parts from their workshop in Australia; the Museum team then altered them to fit for Dakota. The worn-down metal in the front legs, which were very noisy and unwieldy, were replaced with pneumatic tubing and foam. The shoulders and arms are now as padded as a football player’s and the handles of the bike brakes that operate Dakota’s mouth and eyes are more comfortable, too.

"Appendages that became jiggly now move with more stability, and it's quieter, which is wonderful,” says Zajko. “That's a huge improvement for people operating the puppet. She rides like a BMW now—so smooth!”

Don’t Snub the Toe

Doing this once-in-many-millions-of-years remodel meant that staff had the opportunity to make science-based anatomical adjustments. “Krystopher Baioa, a puppeteer who also worked on the restoration, and I looked at the Triceratops skeleton downstairs in the Dino Hall, and we're like, huh, there are five toes on the skeleton, only four toes on our puppet. So, we added a toe!” says Franz.

Dakota's new toenails and foot soles. Each toenail was hand sculpted and painted. The team used durable foam and rubber, the same materials you might find in a pair of sturdy boots.

Emily making a test foot sole. Designs from Erth were the inspiration, but a few different versions were tested before choosing the best one based on durability for the puppet and comfort and flexibility for the puppeteer.

Krystopher adding new texture and paint to Dakota's brow horns.

1 of 1

Dakota's new toenails and foot soles. Each toenail was hand sculpted and painted. The team used durable foam and rubber, the same materials you might find in a pair of sturdy boots.

Emily making a test foot sole. Designs from Erth were the inspiration, but a few different versions were tested before choosing the best one based on durability for the puppet and comfort and flexibility for the puppeteer.

Krystopher adding new texture and paint to Dakota's brow horns.

They also upgraded the audio to allow for truer-to-science vocalizations.

“Originally Dakota sounded a lot like a cow,” said John Conant, the theatrical technician in charge of the audio. “Her sounds were a lot rounder, more bovine, and I wanted to draw inspiration from some of the research that I had seen. There is some fossil evidence that dinosaurs may have had vocal systems more similar to what crocodiles have. It's more of that breathy, “ooh” like a dove cooing. Alligators do the same thing, but much lower. It's just terrifying when they make their noises!”

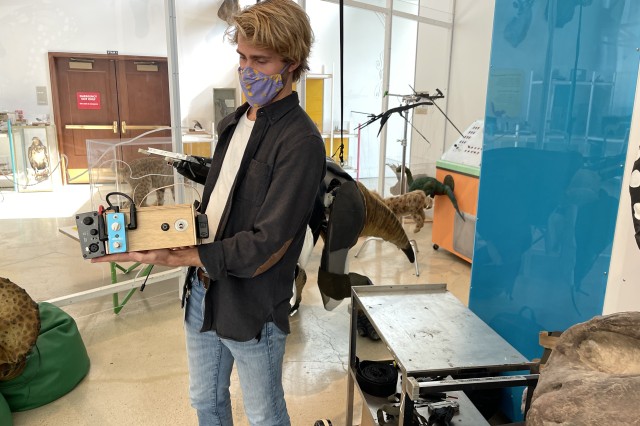

Betsy tests out some roars, grunts, and growls as John makes adjustments for the most accurate Triceratops sound.

Sound installation begins.

1 of 1

Betsy tests out some roars, grunts, and growls as John makes adjustments for the most accurate Triceratops sound.

Sound installation begins.

Hush No More

This audio upgrade included pumping up the volume; the shy juvenile is now four times as loud. The original amplifier was a small sound system, the kind used to play music in trade show booths, so not powerful enough to fill a cavernous diorama hall with plaintive cries or squeals of delight.

“Hunter, the juvenile T. rex puppet, has a souped-up car subwoofer system inside of him. And so the overhaul was to take the same approach with Dakota. It was to get her bass thumping.” Now when she’s sleeping and snoring, or slurping water, visitors can really hear her. Franz says this refurbishment project made the team—and their fabricated, painted muse—more than just literally bonded. “You really start to feel connected to these creatures. They've got so much life in them, and it's a real pleasure to help them keep going.”