BE ADVISED: Monday, February 16, the north entrance on Exposition Blvd will be closed. Visitors may access the Natural History Museum via NHM Commons or the south entrance, facing the L.A. Memorial Coliseum.

Dispatches from the D-ARK

Follow Curator of Malacology Jann Vendetti with updates from an expedition into the deep sea caves around Japan's Minami-Daitō Island

Pictured above: JAMSTEC research vessel Kaimei by IikaJzuchiN licensed under CC BY 4.0

Published May 8, 2024

Dr. Jann Vendetti, NHM Curator of Malacology, is joining an international team of scientists aboard Kaimei, the world’s most advanced research vessel, for an expedition exploring biodiversity in the deep sea caves around Minami-Daitō Island in the Philippine Sea. This JAMSTEC (Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology) and Ocean Census expedition will use deepsea robots and cutting-edge technology to dive into the lightless caves and uncover the marine life that calls them home in a project called D-ARK: Deep-sea Archaic Refugia in Karst. These semi-isolated limestone caves could provide habitats for relict species—"living fossils"—animals once thought extinct that persist on Earth, like the coelacanth on view at NHM.

Vendetti is bringing us along with Dispatches from the D-ARK, a series of updates from the journey.

Dispatch 3: Farewell, Minami-Daitō

May 13–16

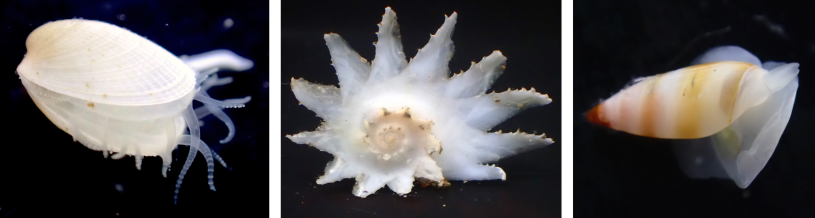

Collage of Mollusks

It has been a banner week for mollusks. This being my first deep-sea research cruise, I’m not making that statement with the wisdom of experience. However, I do know that it is one thing to see a shell in collections (as I typically do) and quite another to see it in its habitat. Seashells are often appreciated for their color, pattern, and shape, all of which are on display here.

A reminder: Mollusks with shells make their shells, and with few exceptions (for sea slug larvae), grow with them and are attached to them for their whole lives.

Guyot sounds like ‘Ghee-Yo’

We said goodbye to Minami-Daitō without ever stepping foot on the island, but having explored some of the biodiversity living in and around its undersea limestone caves. Our ship Kaimei headed east toward a series of seamounts along the Kyushu/Palau ridge. Though these seamounts were formed as an island arc, they are neither islands nor active volcanoes.

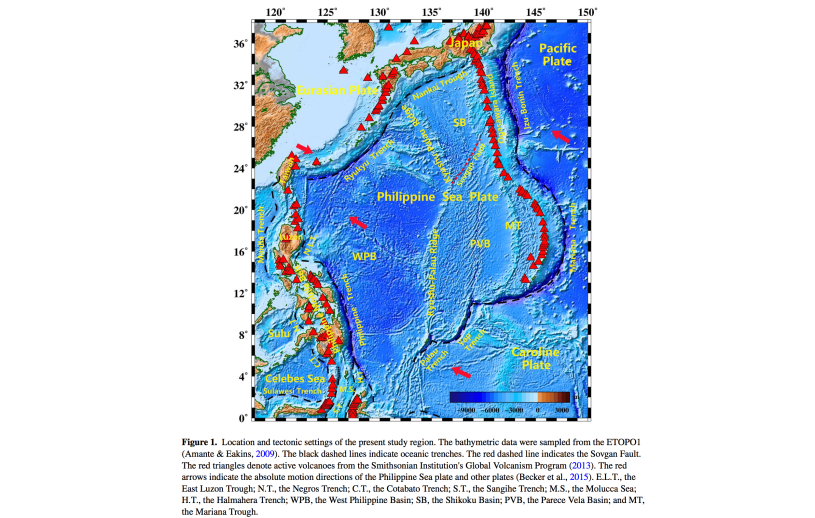

The “not island” explanation is simple: Because the seamount tops don’t break the ocean surface, they are not islands. The “not actively volcanic” explanation requires a map and a little tectonics fluency: About 25 to 28 million years ago, plate subduction created the undersea volcanoes (= seamounts) of the Kyushu/Palau ridge. However, complex tectonic dynamics since then, which influence the Philippine plate today (see maps), have ceased the volcanism of these seamounts turning them into “extinct volcanoes’. Should you lament this loss, there are plenty more active seamounts and volcanoes being created and fueled by the famed Ring of Fire.

A final fact to this earth science story: Some to many of the Kyushu/Palau seamounts aren’t “mounts” at all. Their pointed shape has been eroded, creating a flat, mesa-like structure called a tablemount or guyot (pronounced ghee-yo). The top of one of the guyots we’ve been exploring varies from 330–470 meters deep. If you’ve read this far your rewards are: 1) clarity in understanding seamounts, and 2) the word “guyot” (!), a potential crossword answer, decent point-getter for Scrabble, or a possible win for Wordle.

References

Ishizuka, O., Taylor, R.N., Yuasa, M. and Ohara, Y., 2011. Making and breaking an island arc: A new perspective from the Oligocene Kyushu‐Palau arc, Philippine Sea. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 12(5).

Zhang, T.Y., Li, P.F., Shang, L.N., Cong, J.Y., Li, X., Yao, Y.J. and Zhang, Y., 2022. Identification and evolution of tectonic units in the Philippine Sea Plate. China Geology, 5(1), pp.96-109.

She, L., Zhang, G., Jiang, G., Zhao, D., Xi, J., Lü, Q. and Shi, D., 2023. Slab Morphology Around the Philippine Sea: New Insights From P‐Wave Mantle Tomography. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 128(1), p.e2022JB024757.

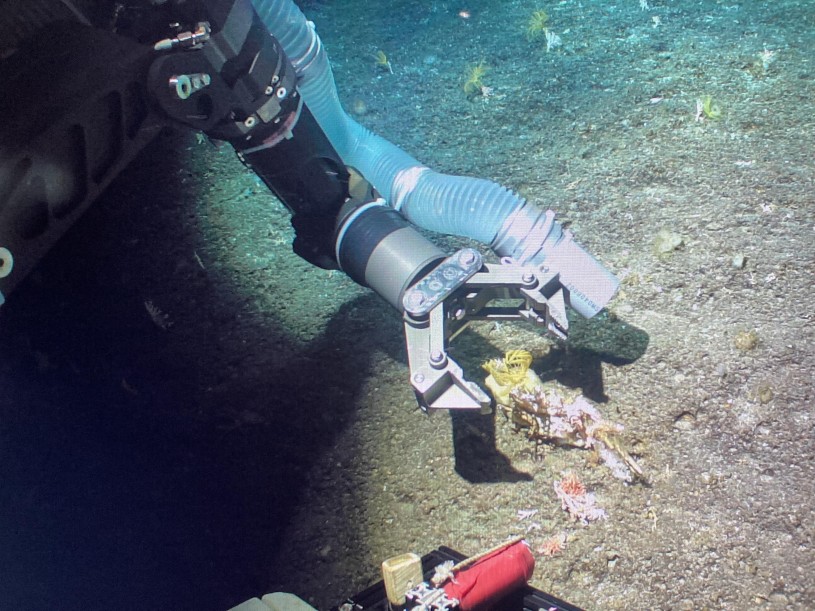

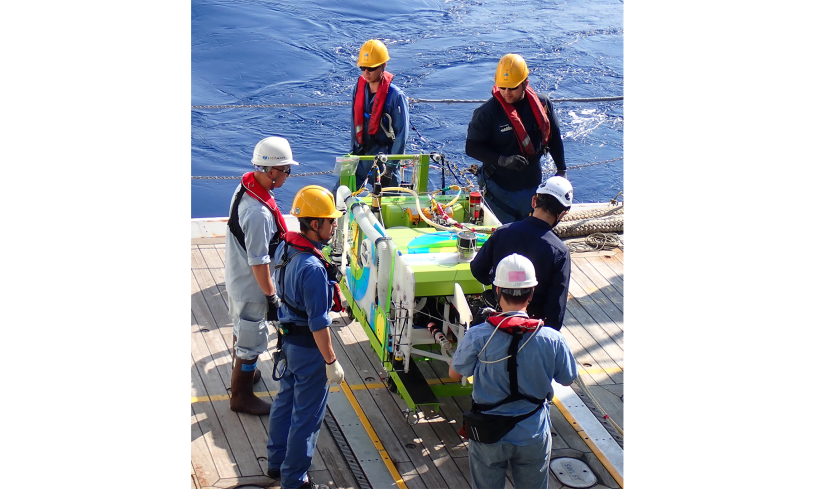

Pilots are a deep-sea scientist’s best friend

At every site we’ve explored, one of the ship’s two ROVs has been deployed. Neither has a person inside it, thus the RO (Remotely Operated) in ROV––remotely operated vehicle(s). In ocean exploration these are sometimes known as ROUVs: Remotely Operated Underwater Vehicles (not to be confused with ROUSs). The ROVs of Kaimei are tethered to the ship and have moveable jointed arms, a suction tube, lights, boxes, and canisters for specimen storage, thrusters for propulsion, and up to five cameras to record what is happening. The pilots of these complex machines are onboard the ship in a specialized command room but are in constant communication with scientists by radio. They focus the ROV’s camera(s) on known and mysterious creatures while the scientists debate their taxonomic identity and whether they should be collected (the creatures, not the scientists). The pilots reposition the ROV when a scientist asks to check out what might be a rare or new species of something (a snail, fish, coral, sea cucumber, etc.). The pilots do this while simultaneously steering the ROV, negotiating ocean currents and bathymetry, and manipulating and deploying various analytical tools.

The scientists gather near the bridge of the ship to watch a live feed of the ROV camera footage on several large monitors. So far, Kaimei’s ROV pilots have navigated ocean caves without incident and deftly collected dozens of specimens from the seafloor and water column. After a successful specimen-collecting event, the scientific team often cheers and applauds the ROV pilots who are still busy piloting and, alas, out of earshot.

What the Philippine Sea and the Mojave Desert have in common

On the flat top of the seamount we’ve explored are expanses of sand and rock depauperate of visible life, interrupted by oases of animals associated with an upright structure. At 300–400 meters deep, this relief is usually a soft or wiry protein-bodied coral. These are not the stony corals, colonial creators of shallow tropical reefs, but their evolutionary siblings––fleshy and flexible, whip-like, or branching. At their base are hermit crabs, on their stalks are snails, swimming nearby are fish. Clinging to them are often one or more species of sea star or feather star (members of the weird and wonderful phylum Echinodermata), looking very plant-like as if they were flowers. Indeed, marine communities in which animals provide the structure that is usually created by plants in terrestrial environments have been called “marine animal forests”.

At upper bathyal depths (deep, but not that deep), there are no forests of animals or plants, but the mini oases of animals that do live there remind me of a plant-dominated environment of eastern Los Angeles County (and beyond) –– the Mojave Desert. Both habitats share expanses of low biodiversity, punctuated with life. In the Mojave, upright structure is provided by Joshua trees, with a menagerie of animals using them as their home. Among downed branches and leaf litter are snails, wood rats, beetles, and snakes; among the upright branches are owls, lizards, shrikes, and (famously) moths. That similarly structured microhabitats exist in such different ecosystems is a testament to the universality of interactions between species––what is studied in the branch of biology called ecology. That there are snails in the Mojave Desert and bathyal Pacific Ocean exemplifies the remarkable diversification of these animals and the unifying theme of all biology: evolution.

Reference

Rossi, S., Bramanti, L., Gori, A. and Orejas, C., 2017. Marine animal forests. The Ecology of Benthic Biodiversity Hotspots. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Until next time...

Dispatch 2: A Tour of Mollusks

April 30

On the first dive of the expedition, the Kaimei ROV (ROV = remotely operated vehicle) was deployed for exploration and specimen collection. This ROV has filmed and collected specimens for JAMSTEC since 2016 and can descend to 3,000 meters (~9,843 feet).

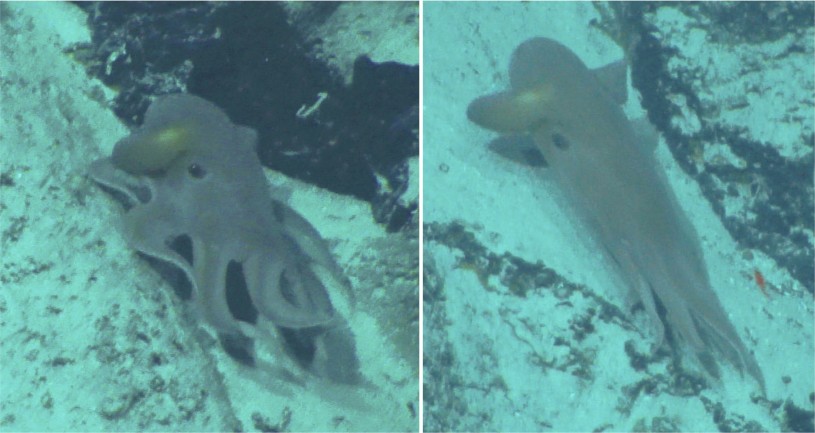

Near the edge of the Minami-Daitō seamount and at 797 meters deep (2,615 feet) one of the first animals we saw was a cirrate octopus, likely a species of the genus Grimpoteuthis. These mollusks have received some attention recently, being nicknamed the “Dumbo octopus”, and noted for their cuteness. The Dumbo elephant ear-like projections are really a set of paired and ridged fins that attach internally to a shell. That’s right! If you know anything about octopuses, you’re likely confident that they are the one group of living cephalopods (of the squid, cuttlefish, Nautilus, and octopuses) with no internal shell. Nope!

These octopuses have an internal shell that is small but important. It varies from horseshoe-shaped to bow-tie-shaped and connects to the paired fins (ridged from internal cartilage) with specialized muscles, allowing these animals to swim. That is, the cirrate octopuses can power their movement by slowly "flapping" their fins, which is what we observed. These amazing octopuses have semi-gelatinous bodies and live exclusively in the deep sea, having been observed at a maximum of 7,000 meters deep (22,965 feet, ~4.4 miles).* So much is still left to learn about these mollusks; it was thrilling to see one!

*For context, the deepest known place in the world’s oceans is called the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench and its depth is about 10,971 meters (35,994 feet, 6.8 miles). That is deeper than Mt. Everest is tall at 8,848.9 meters (29,032 feet, 5.5 miles).

References:

https://www.marineregions.org/

Collins, M.A. and Villanueva, R., 2006. Taxonomy, ecology and behaviour of the cirrate octopods (in Oceanography and marine biology: An annual review 48: 277–322.

May 1

This was the first dive of a small ROV called Crambon during this expedition, and the first time it had been used since 2019.

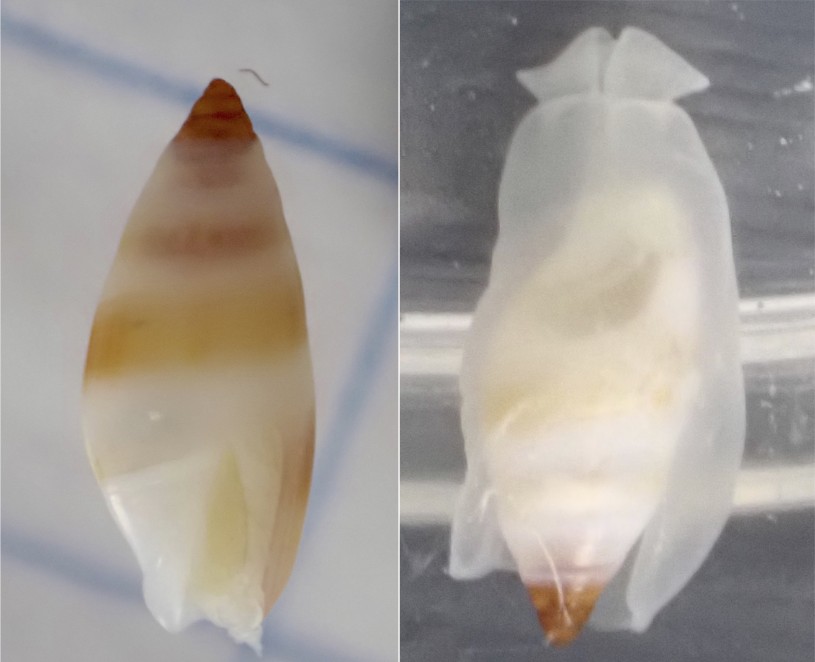

This ROV collected sediment samples within which was this micro gastropod (= small snail). It is about 0.6 cm long and currently un-identified by me. The shell with the apex (the pointed end) up is usually how snail shells are depicted in books, but in life the head end is that of the aperture (where the shell opening is). This remarkable micro snail covers its shell in a white sheath-like mantle.

Similarly tiny snails were also collected in sediment samples by the Kaimei ROV. The reason they are called micro gastropods is evident here, with a penny for scale.

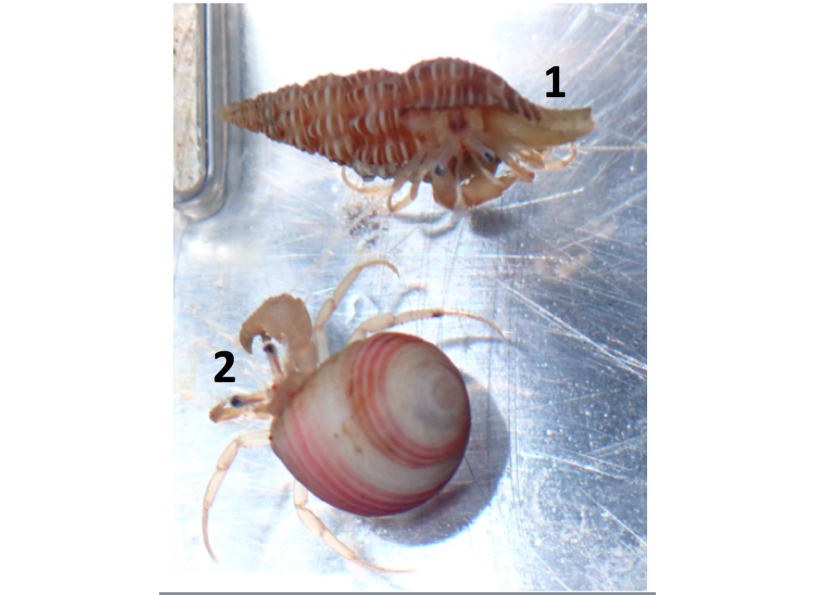

Over the last week, I’ve been consumed by attempts to identify several snails collected at depth. Here are two, both of which (in a separate HOV dive) were also found “crabbed”, that is, having their empty shells inhabited by hermit crabs:

The first is a gastropod brought up with deep sea Asteroidea, or sea stars, in the genus Brisinga. These sea stars are amazingly long-armed and orange, and the snail with them has a brown and white striped shell, bright yellow body, and a short siphon.

The second is a snail in the family Colloniinae, which are characterized by a round aperture (shell opening) and a calcareous operculum (a hard calcium-rich “trap door”). This one has a pink and white striped shell and brown and white striped foot and looks to be a species of Bothropoma or Collonista.

Finally, this “crabbed” shell is a species in the genus Bursa. You can see this awesome hermit crab securely in the Bursa shell, then nearly completely out. Unlike snails, hermit crabs can leave a snail shell and find a new one when it suits them. For snails, their shell is their forever home, and one of their own making.

Until next time...

Dispatch One: April 27 & 28

I traveled from the Tokyo Haneda airport via a train, the shinkansen, and another train, to Shizuoka, Japan from which the Kaimei Research/Survey Vessel would launch. A half day to acclimate gave me enough time to find and explore a local temple, Seiken-Ji.

Prior to the D-ARK and Ocean Cenus expedition setting off, the returning research cruise disembarked. Although their focus was not deep-sea biodiversity, they collected living Calyptogena sp. clams from a methane cold seep off of Hatsushima Island in Sagami Bay, central Japan, for Enoshima Aquarium in Kanagawa Prefecture. Calyptogena bivalves harbor chemosynthetic bacteria in their gills and have hemoglobin in their soft tissues, making it red.

They live in total darkness at depths between 900–1200 m and were collected using a submersible equipped with a camera, collecting arms, and collection containers. They are going to be included in the Aquariums's Deep Sea exhibit associated with JAMSTEC and be part of research within its Breeding Department Exhibition and Breeding Team: https://www.enosui.com/en/exhibition.html (See Deep Sea Part 1: Joint Studies with JAMSTEC). [Personal note: when I saw these I gasped out loud. We have shells in the NHMLAC collections, but I'd never seen these animals alive. It was amazing.]

We are en route to Minami-Daitō Island in the Philippine Sea, a small island off of which there are deep sea limestone caves, which is the first stop of the research cruise.