An Ocean of Worms

Discover an underwater world of incredible marine worms in the ancient rocks off L.A.’s coast

Published July 4, 2023

Just offshore of Los Angeles and surprisingly close to the surface, lies a reef made of rocks dating back 10 to 15 million years ago.

These shales date back to the Miocene epoch, an age when the waters teemed with strange whales, giant sharks, and the first seals and walruses. While many of the wondrous animals of that epoch have long since vanished from the oceans, the worms beneath them survive—as they have since first appearing in the Cambrian around 520 million years ago.

You don’t make it through five mass extinctions without picking up a few evolutionary tricks. Marine worms fill every ecological niche in the oceans, from beaches to volcanic sea vents on the ocean floor, eating everything from plankton to the bones of whales. In many areas of the seas, worms are both the most common animals and the most diverse, but chances are you haven’t seen them when you take a dip. If you did notice them, you might have seen what looked like a piece of string. To Leslie Harris, Collections Manager of Polychaetes at the NHM, each one is a strand in the incredible tapestry of the marine worms she studies.

“One reason why I take photos of ocean worms and other critters is that it's fun. But another reason is precisely because so many people have absolutely no idea of the range of marine diversity,” says Leslie Harris, Collections Manager of Polychaetes at NHM.

On a recent expedition to the shale reef with Dr. Kimo Morris and his class from Santa Ana College, Harris collected and photographed the marine worms pictured in this photo essay, adding to NHM’s collection of several million specimens. “If you say, 'I study worms' people say, 'Ew, that's disgusting.' And because of things like that, I want to show them just how beautiful they are and their amazing diversity.” Dip your toe into the ocean of the incredible invertebrates she studies, and discover the wonder of these worms for yourself.

Things like worms and sponges and so many other things, they're inconspicuous. They're not something you normally notice...or people recognize even as animals. So much of the animal world is just beyond our vision

Leslie Harris

image by Leslie Harris

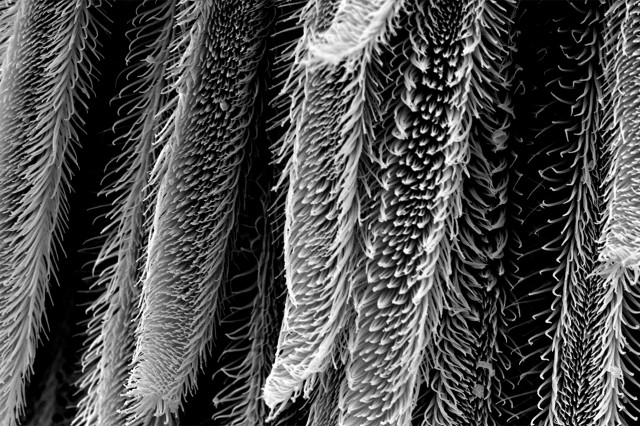

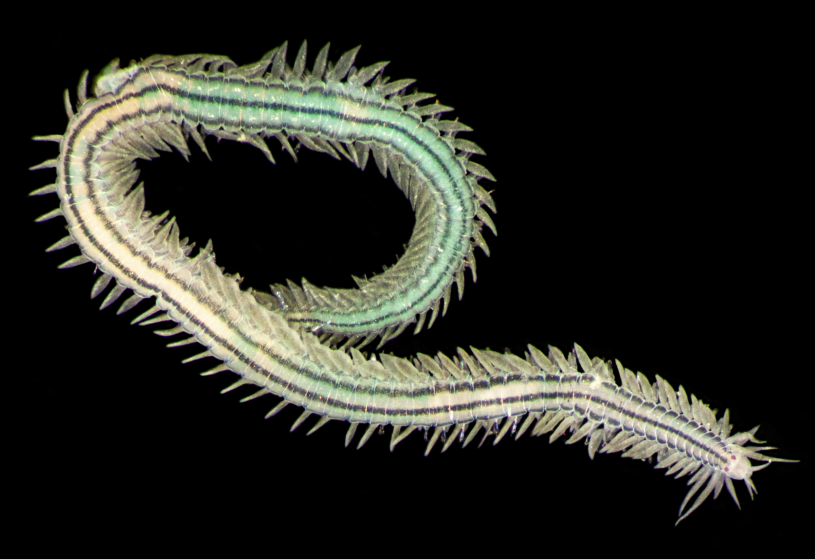

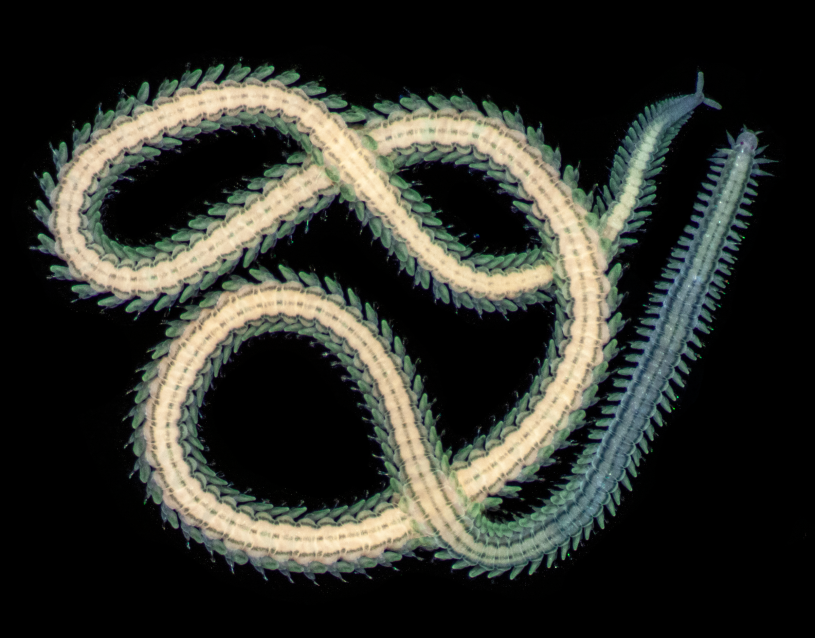

Polychaetes (rhymes with ‘dolly feets’) are, in theory, simple creatures; they have a head and a tail, and a body made out of segments, usually with one pair of parapodia (pseudo legs) per segment holding the bristles that give these marine worms their name (polychaete means ‘with much hair’ in Greek). Their “simplicity” does not mean less evolved—these worms have just found the most elegant solutions to survival.

iNaturalist observation by Leslie Harris

Segments are the secret sauce of these incredibly successful invertebrates. Each repeating unit has its own body cavity complete with many of the organs necessary for survival. From this simple scheme, more than 10,000 species of incredible variation continue to bloom: brightly colored, camouflaged, shimmering, slimy, and everything in between.

image by Leslie Harris

Their leg-like parapodia have evolved to be paddles for swimming, legs for walking, shovels for burrowing and so much more: “They can use the bristles for defense and they can use their parapodia in making the tubes that they live in,” says Harris. “The shape of those bristles and the distribution along the body are some of the very important characteristics that we use to identify them.”

image by Leslie Harris

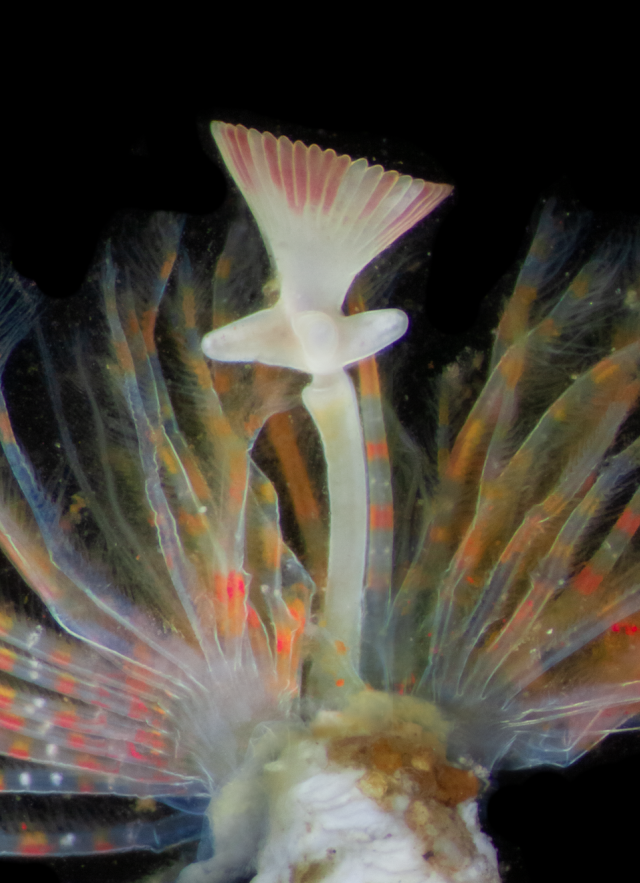

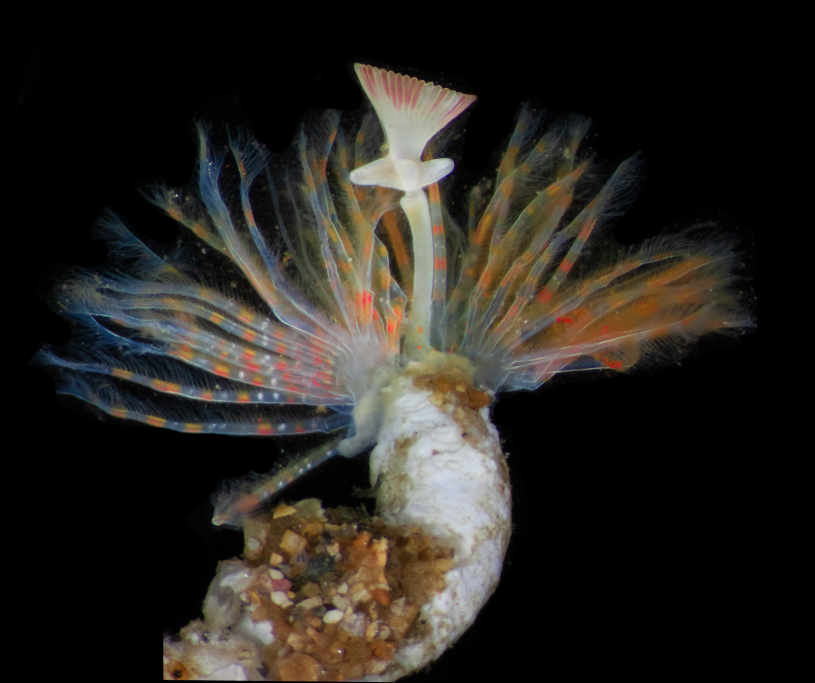

The burst of color you’re seeing is this feather duster worm's modified gills, catching and feeding on whatever floats by in the water. “All those thousands of little tiny hairs act as a conveyor belt to take the hairs down to the mouth, which is down in the middle, down at the base.” They also absorb the oxygen they need to live. Look closer, and you can see how these worms see.

image by Leslie Harris

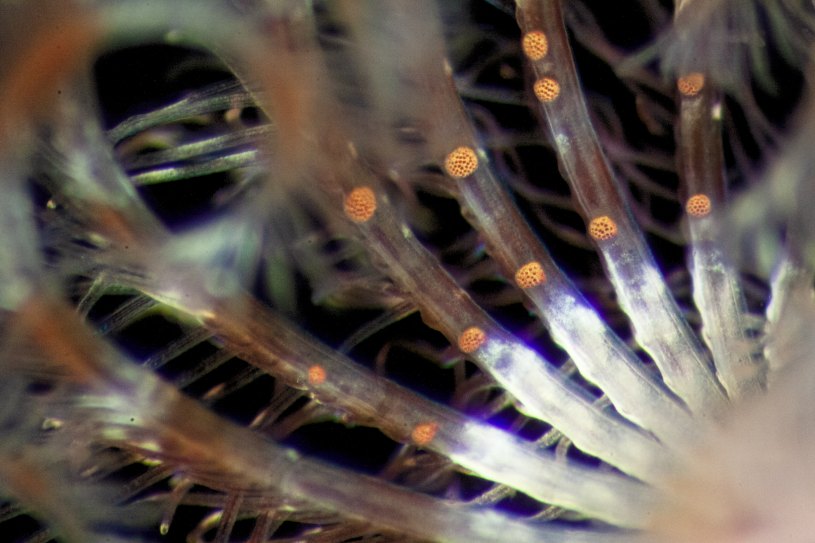

These orange orbs are the worm’s eyes. “These are compound eyes, made up of many simple eyes each with its own lens.” Mostly they detect darkness, light, and movement. “So if you come near one of these in the ocean and it's fully extended out feeding, the minute it detects your shadow or the pressure wave from your moving the water, it instantaneously retracts down into its tube.”

image by Leslie Harris

Some worms, like the feather duster above and this Crucigera websteri build tubes for protection. This species builds its own tube by oozing out a material that combines with calcium in the water to harden around its body, anchoring it to rocks, shells, corals, and pilings. This worm may have hitched a ride to the L.A. area from the East Coast via the shipping trade.

image by Leslie Harris

Other polychaetes cement grains of sand to construct their tubes, like this Neosabellaria cementarium, adding more sand to expand their tubes as the worms grow. While some tube-building worms combine their efforts with enough individuals to form distinctive honeycomb-like reefs, N. cementarium’s tubes are arranged in random squiggles. They feed by catching food particles with their fine tentacles.

image by Leslie Harris

This explosion of tentacles is a member of the aptly named spaghetti worm family Terebellidae. It’s called Polycirrus Latin for “many filaments”. “They have a habit of losing their heads when they're stressed. Think of lizards that lose their tails and scurry away while the tails distract the predator. Well, Polycirrus detach their heads,” says Harris. “And now the predator can eat that part and the rest of the body slithers away or goes deeper into its tube, and it will regrow a new head and anterior body.”

image by Leslie Harris

Another member of the spaghetti worm family that managed to keep its head on its segmented body—the segments help taxonomists like Harris identify the species. Where the human eye on its own might see a string—if anything—in the water, microscopes help Harris explore the finer details of these overlooked animals and share their distinct beauty with the world.

image by Leslie Harris

Up close, polychaetes can be as cute as they are fascinating. This chubby-looking specimen is part of the incredible transformation some marine worms go through to reproduce. When the breeding season begins, some species develop new segments and even completely new individuals from their rear ends. These epitokes are filled with gametes–sperm and eggs–and break off from the original worm to produce the next generation.

image by Leslie Harris

“Things like worms and sponges and so many other things, they're inconspicuous. They're not something you normally notice...or people recognize even as animals. So much of the animal world is just beyond our vision,” says Harris.

“We're finding out all the time how much we don't know about what lives in our oceans and we're constantly finding new species. Here in California, our marine invertebrate fauna is one of the best known in the world, especially the worms,” says Harris, but she emphasizes that there’s so much more to learn.

photo by Jody Martin

She has an ongoing list of over 300 undescribed species she’s found on the coast from California through Alaska, quietly living their extraordinary lives in places most people just aren’t looking. The European naturalists who first described the worms in the 1890s compared them to species they knew and often grouped similar-looking worms into one species with a worldwide distribution. Modern DNA analysis shows that despite their similarities there are distinct regional species. It’s a tangle of contradictions like the worms themselves: ubiquitous but often unseen, 500 million years on Earth but alien to most human eyes, well-studied by scientists like Harris but with many unknowns.

What we don’t know is what these overlooked species are doing exactly. What happens as they thrive in or succumb to a changing, warming planet? What do they feed on, and how do they reproduce? What other animals and systems do they need to survive? What other animals depend on them for their survival? The web of life can be as hard to see as a marine worm with the naked eye, but NHM collections can help scientists see the answers before it’s too late.

Our 300,000-years-long span on Earth is just a ripple compared to polychaetes’ hundreds of millions of years in the seas. It’s the worms’ ocean, and we’re all just swimming through it.

By Tyler Hayden