The Dino Artist

Stephanie Abramowicz, illustrator in our Dinosaur Institute, has brought Gnatalie, the Green Dino, into full color. The paleoartist who also helped dig up the long-necked dinosaur—soon to be on display in the Museum’s new wing, NHM Commons—talks about how she uses scientific evidence to paint the prehistoric.

Published September 3, 2024

Stephanie Abramowicz, illustrator in our Dinosaur Institute, is a paleoart alchemist; she gathers all the scientific research available—from measurements to morphology—and meticulously transforms the data and analysis into fleshed-out pictures of the prehistoric past. The Senior Paleontological Imaging Specialist, who holds a BFA from the Roski School of Fine Arts at the University of Southern California, conjures creatures that bounded around the planet between 250 and 66 million years ago, a period known as the Age of Dinosaurs.

In her 18 years at NHM’s Dinosaur Institute, Abramowicz has crafted fleshed-out illustrations of the duck-billed Augustynolophus, California’s state dinosaur, a fierce juvenile T. rex, a chunky Triceratops, a swimming Polycotylus latipinnis, a marine reptile, all of whose bones are on display in NHM’s Dinosaur Hall.

But her latest feat of artistry—a green-hued Jurassic giant—is her most personal to date. Abramowicz was on the Dinosaur Institute crew that in 2007 discovered Gnatalie (pronounced “nat-ah-lee”), affectionately nicknamed for the biting gnats that pestered its excavators during the digs. At more than 75 feet long from nose to tail, the long-necked dinosaur will soon be on display in the Museum’s new wing—NHM Commons.

Illustration by Stephanie Abramowicz

It is the most complete sauropod skeletal mount on the West Coast—and the only green-colored dinosaur skeleton on display worldwide. The unusual bone coloring is due to infilling by the green mineral celadonite during the fossilization process. Sauropods—who all have long tails, four pillar-like legs, long necks and relatively tiny heads—include the most enormous dinosaurs known to science.

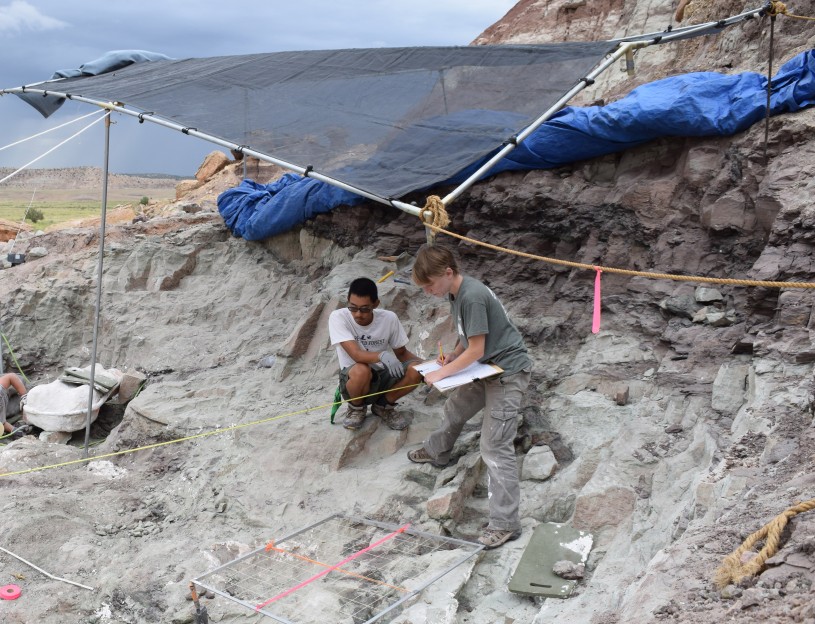

Abramowicz will never forget when she first planted her boots on the ground in southeast Utah where a collegial crew, led by Dr. Luis Chiappe, NHMLAC Senior Vice President for Research and Collections and Curator at the Dinosaur Institute, first prospected in the dusty expanse of sandstone. They would spend every summer for the next decade in this hot desert quarry, unearthing fossils of sauropods, a family of dinosaurs alive 150 million years ago.

“I definitely feel really connected to Gnatalie. I've spent so many months of my life out in the field breathing the dust and living in that environment where Gnatalie walked so many millions of years ago,” Abramowicz said. “And it is extremely special to have had those experiences of unearthing the fossils and seeing them see daylight for the first time in millions of years.”

“Stephanie is much more than a skilled paleoartist,” says Chiappe, “she has carefully documented—through illustrations, photography, and footage—every aspect of our many field expeditions and post-field research, thus leaving an archive of decades of work that have underpinned the magnificent dinosaur displays at the Museum.”

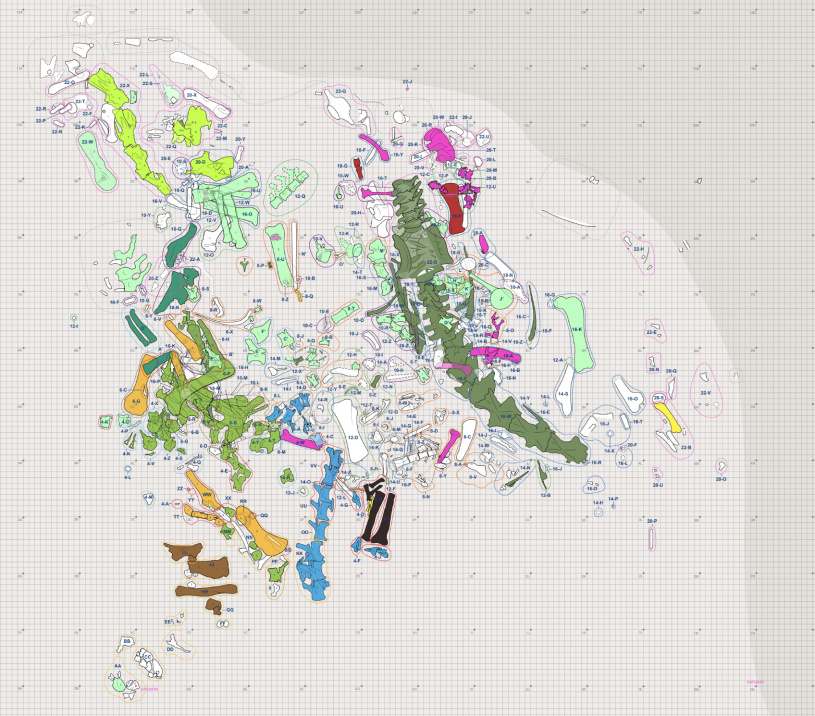

With whirring power tools, chisels and hammers, the crew exposed each fossil find, clearing away the loose rock and applying glues to stabilize the bones, and making necessary repairs. When she wasn’t excavating, Abramowicz was constructing a detailed map of the bone bed. Like a cartographer hundreds of years ago meticulously recorded the longitude and latitude of newly discovered lands on parchment paper, she was also creating a map by hand.

Strong strings laid across the quarry in a grid system served to identify where each bone—humerus, femur, dorsal vertebra—laid and to which individual animal it (probably) belonged. This color-coded map shows that there were many sauropods jumbled up together in the quarry. The scientists said this colossal pileup was a result of bones being swept over eons into an ancient flood plain; geological forces over millions of years helped to elevate the Jurassic bounty to within a human’s-arm’s-reach. The mounted Gnatalie skeleton that museum visitors will see on display is a composite of multiple specimens, all belonging to the same sauropod species.

When the crew was done for the summer, the bones that they had swaddled in protective “jackets” (tissue, burlap, and plaster wrapping that protects the fossils) were hauled back in trucks 800-plus miles to NHM’s Dinosaur Lab where the emerald-hued fossils were prepared for display. Once Abramowicz was back in her office, with the map, photos of each bone, and the actual specimens cataloged and resting in drawers in the Dinosaur Institute’s collections rooms nearby, she went to work. She created a carefully reconstructed illustration of Gnatalie’s skeleton and head, and then, married the scientific evidence with her imagination to render the massive herbivore in full color.

“I gathered all the reference material that I could, starting with the actual preserved fossils…in terms of what her skin looked like, what color would the creature have been, what would be the soft tissue anatomy for her nostrils…none of that is preserved in this quarry,” she said, “I’d then talk with the scientists and the other researchers involved to get their best guess of what references to use to fill in the gaps.”

Abramowicz will then make a clay model that she can rotate around and use like a three dimensional sketch to get some interesting perspective and foreshortening, and play with lighting. Using graphic design programs and other tools, she considered the shading and shadows that would indicate what scientists know about the girth, gait, or movement of the dinosaur.

“For two decades, Stephanie has brought to life an array of dinosaurs on display at NHM,” says Chiappe, “her talent, attention to detail, and scientific accuracy, have greatly contributed to our exhibitions and to make our Museum the dinosaur hub of the West Coast.”

“[The data] helps me connect with the creature as an individual. It's not just some generic dinosaur; it's this creature. This bone came out of the body of this animal, and it was just as real as I am.”

She says it’ll be thrilling to see awestruck visitors looking up at the green giant. “It was clear Gnatalie was speaking to us, released from the ground and ready to live another life.”

Marvel at more of the artist's Gnatalie and non-Gnatalie illustrations in the gallery below.

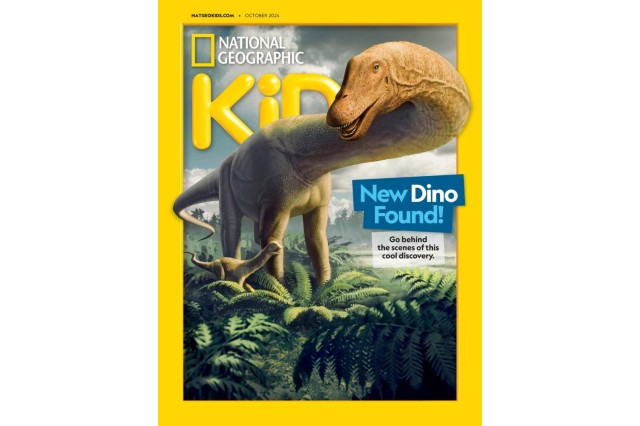

Gnatalie graced the cover of the October 2024 edition of NatGeo Kids

Stephanie Abramowicz

Fleshed-out illustration of Thomas the T. rex, one of the stars of NHM's Dinosaur Hall

Stephanie Abramowicz

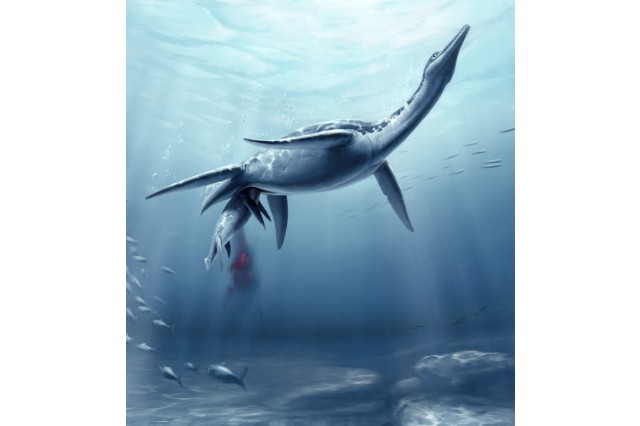

An illustration of a pregnant Polycotylus, also known as Polly the Plesiosaur, whose magnificent fossils are on view in the Dinosaur Hall.

Stephanie Abramowicz

An illustration of a group of Dromomeron romeri pausing for a drink. Read about the research.

1 of 1

Gnatalie graced the cover of the October 2024 edition of NatGeo Kids

Fleshed-out illustration of Thomas the T. rex, one of the stars of NHM's Dinosaur Hall

Stephanie Abramowicz

An illustration of a pregnant Polycotylus, also known as Polly the Plesiosaur, whose magnificent fossils are on view in the Dinosaur Hall.

Stephanie Abramowicz

An illustration of a group of Dromomeron romeri pausing for a drink. Read about the research.

Stephanie Abramowicz