Dusting off Old Bones: A Whale’s Tale

The Museum's ambassador, of sorts, a fin whale specimen "swimming" in a glass pavilion, gets spruced up for soon-to-be arriving museum fans

NHMLAC has been doing a little spring cleaning. Gardeners pruned the botanical showstoppers in the Nature Gardens, and an Operations crew scrubbed the six-stories of glass windows of the Otis Booth Pavilion so the cube would sparkle against the blue sky.

Jorge Velez-Juarbe, NHM’s Associate Curator of Marine Mammals and a whale expert, thought the Pavilion’s majestic resident, the skeleton of a Northern Pacific fin whale, Balaenoptera physalus velifera, was due for a little spruce up, too. After all, the much-marveled-at leviathan, suspended in a dive position above the North Entrance, is our museum’s ambassador, of sorts.

But how does one expertly brush the dust off the 200-plus bones of the second largest animal species on Earth? That’s one feat no one had attempted since the whale began its mid-air plunge in the summer of 2013, the year that the towering Pavilion surrounded by gardens was unveiled for the Museum’s 100th anniversary party.

Paleontological Aerial Artistry

The first order of whale-cleaning business was the commandeering of a boom lift. The solid contraption, commonly used by movie crews to record scenes, was the best bet to hoist his colleague Vertebrate Paleontology Preparator James Preston up high enough to get him close to the 63-foot long specimen. The building and operations staff happened to have one handy they were using for another purpose, so the mammalogy maintenance duo were in luck. Then, it was the matter of selecting the appropriate cleaning implements.

“The approach, at first, was to use the leaf blower, but wasn’t working with the dust bunnies,” said Velez-Juarbe. They had to switch up the tools and swap the blower for a feather duster. “It was dusty. I can tell you that! At some point, it looked like it was snowing.”

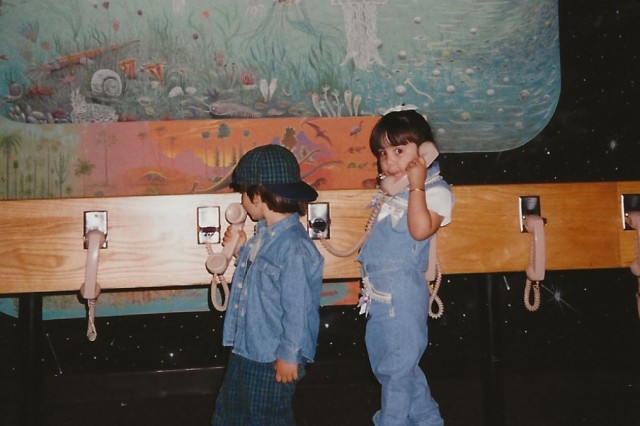

Preston had training and experience in such lofty fossil-cleaning maneuvers, having brushed off the specimens of a pigmy sperm whale, two dugong/manatees, and an ancient sea lion relative “swimming” overhead in the Age of Mammals hall. But the fin whale was leagues larger. It took Preston hours to brush the torso, flippers and head (he couldn’t approach the tail, alas, because the lift wasn’t tall enough.)

Photo by Edgar Chamorro

A view of the fin whale cleaning in progress from outside the six-story-high Otis Booth Pavilion. The engineering stunner was created from 139,000 pounds of glass.

Photo by Edgar Chamorro

James Preston, NHM's Vertebrate Paleontology Preparator, waits for a lift.

Photo by Edgar Chamorro

What a sight. From this window-rich vantage point, the glass towers of the downtown L.A. skyline are visible on a clear day.

By Edgar Chamorro

Hand-to-flipper contact achieved! High five? Actually, those massive appendages contain dozens of bones, some equivalent in size to an adult human.

1 of 1

A view of the fin whale cleaning in progress from outside the six-story-high Otis Booth Pavilion. The engineering stunner was created from 139,000 pounds of glass.

Photo by Edgar Chamorro

James Preston, NHM's Vertebrate Paleontology Preparator, waits for a lift.

Photo by Edgar Chamorro

What a sight. From this window-rich vantage point, the glass towers of the downtown L.A. skyline are visible on a clear day.

Photo by Edgar Chamorro

Hand-to-flipper contact achieved! High five? Actually, those massive appendages contain dozens of bones, some equivalent in size to an adult human.

By Edgar Chamorro

This magnificent creature has a fraught backstory. The animal met its fate in 1926 at the hands of whalers from the California Sea Products Company. NHM bought the specimen from the company shortly thereafter to be part of the osteology collection, which allows scientists who study skeletons to learn more about those marine mammals.

Since the whaling era ended, and the protection of the iconic species and other marine creatures strengthened in the 1960s, whale species numbers have been on the rise. Being a friend to these cetaceans has its rewards. Preserving species like whales, which have been evolving here for millions of years, can be beneficial to the environment, and us, in many ways.

“One of the cool things about whales is this phenomenon called the whale pump. When they poop, that increases the nitrogen, which serves as fertilizer for plankton, which then trickles down to rest of the food chain. It’s a beautiful system.”

Jorge Velez-Juarbe, NHM's Associate Curator of Marine Mammals

“One of the cool things about whales is they are essential to coastal marine ecosystems because there’s this phenomenon of the whale pump,” says Velez-Juarbe. "When whales are close to shore they eat small crustaceans and fishes like krill and sardines, for example. When they defecate, they release organic material and nutrients that feed the ecosystem. Algae grows, which feeds fishes and larger organisms. When whales poop, they increase the nitrogen which serves as fertilizer for plankton, and that trickles down to rest of the food chain, including species of fish that are commercially important for us. It’s a beautiful system.”

Our modern marine ecosystem has evolved over millions of years and created a balance that is to be maintained. We hope that the presence of a Balaenoptera physalus velifera in the Pavilion inspires both wonder and responsibility for our oceans so our whale friends can continue to bound and rebound off our California coast for eons to come.