The Lights Below

A new study shines a light on the mechanics of bioluminescence in the rare fish Vinciguerria mabahiss and we explore some of the other fish lighting up the deep

Published March 26, 2025

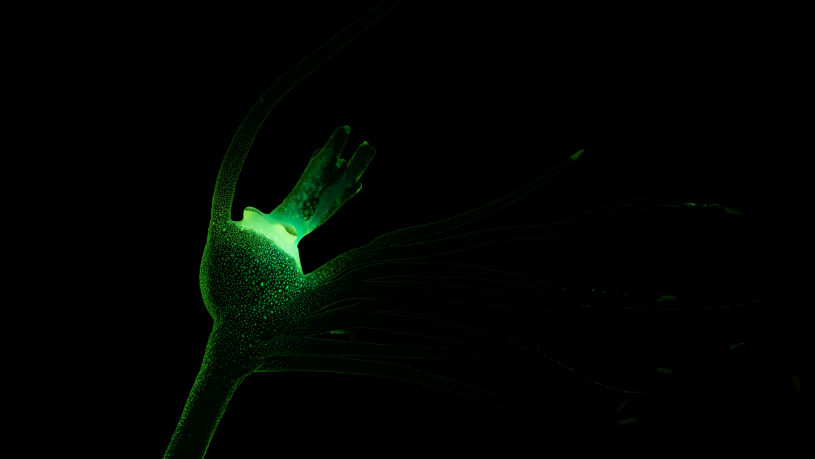

Few survival tools are as magical as bioluminescence—the biological production of light. The lures of anglerfish immediately come to mind like some kind of fairy tale from the deep.

Beguiling lights in the complete darkness of the abyss draw unsuspecting prey to mouths reamed with needle-like teeth. But bioluminescence has evolved roughly 27 times in the long history of fishes, and they light up for all kinds of reasons. The full spectrum of its uses is still being studied by ichthyologists—fish scientists—like Dr. Todd Clardy, Collections Manager at NHM’s Ichthyology Collections. His research has revealed that one rare fish shines with light in the deep to avoid being seen by predators.

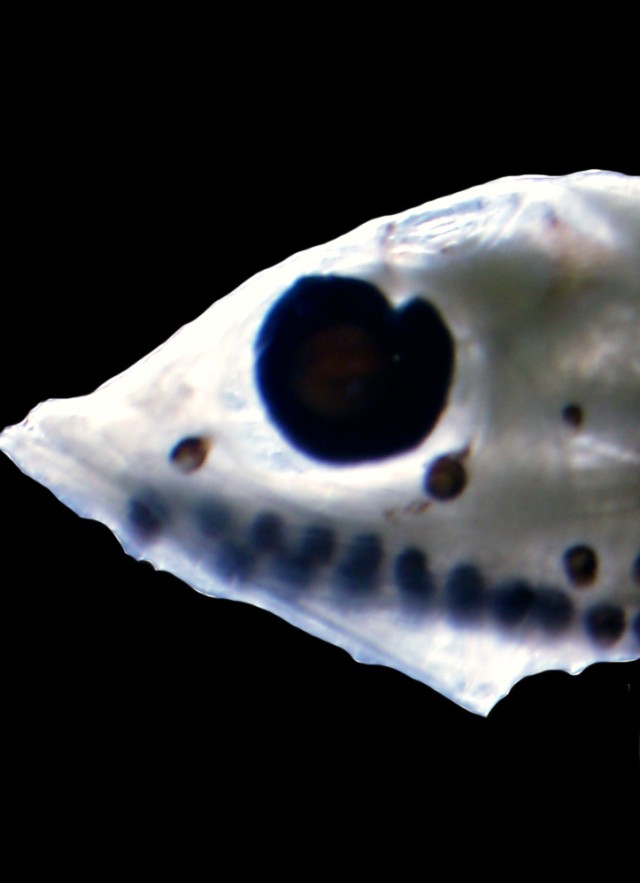

In a new study published in Ichthyological Research, Clardy and his co-authors studied the organs that produce light in Vinciguerria mabahiss, a rare species of fish from the Red Sea. This paper marks the first-ever close examination of these organs, providing key information on their structure and how V. mabahiss uses bioluminescence to make its way through the water—and laying the foundational groundwork for future scientists studying fish bioluminescence.

“There are a lot of different ways that fish go about producing and using light,” said Clardy. “One of the things that we wanted to do was find out how this species of fish was using the light it produced. And part of that was by examining the structure of the photophore and not just how they looked at the cellular level, but we examined the size and the distribution of them across the body of the fish to try to assess what this fish was doing with these cool photophore organs, and it turns out they're using it as counter illumination.”

While most of us might think of bioluminescence as an attractor, Clardy and his teammates found that V. mabahiss used its light to hide. Counter illumination is a kind of camouflage where an animal produces light to make itself harder to be seen by predators.

“We live in basically a two-dimensional world,” said Clardy. “I never think to look for a cheeseburger up above me. But fish are always looking up for a shadow passing over them because it’s either going to be food or a predator.” Counter illumination breaks up that shadow to mimic the light of the surface. “The fish is camouflaged, almost invisible.”

Megamouths, Footballfish, and Other Lights Below

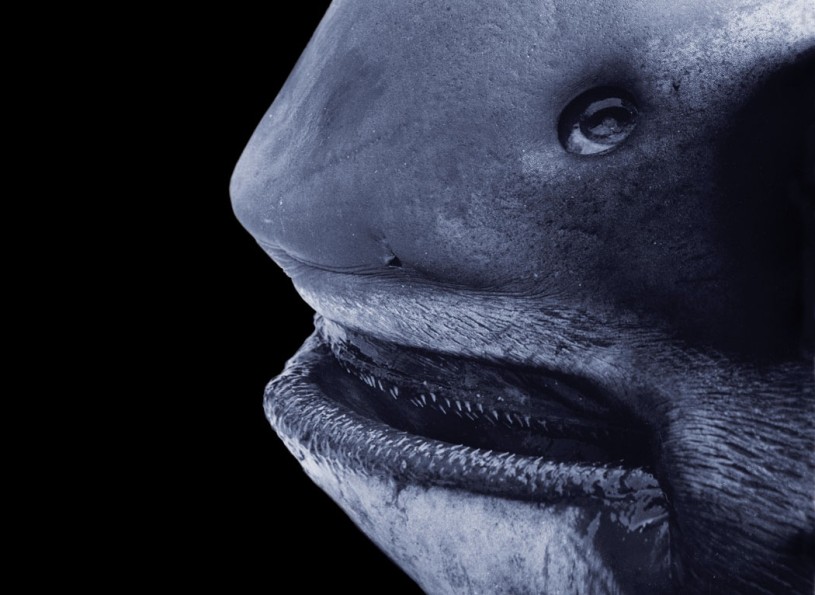

In the deep dark sea, light is something that some animals just can’t ignore. Anglerfish use their lures, or esca, to attract unwitting fish in the abyss with glowing bacteria called photobacterium. The megamouth shark has a light-up mouth that scientists long thought was bioluminescent, but more recent discoveries revealed that the gentle giants were lighting up with the help of their prey—tiny plankton—and the greater brightness is actually the result of highly reflective scales around their (mega)mouths.

“Basically, megamouth sharks wear glowing plankton-like lipstick to attract prey,” said Clardy.

Lanternfish have photophores on their bellies for camouflage, like V. mabahiss, but also on their sides. Researchers think those lights help with communication and mating. Lanternfish are an incredibly diverse group with more than 250 species, and their bioluminescence helps them identify appropriate mates. The pattern of lights they produce helps different species identify each other.

These are just some of the ways that fish make light. The variety of uses and methods for illumination in fish highlights the importance of studying bioluminescence. Understanding the organs each fish uses to emit light is key to building our understanding of this flashy survival tool.

Fish Light Bulbs

Clardy and his team found that V. mabahiss have between 140 and 144 photophores of varying sizes throughout their bodies, all pointed downwards. Each photophore produces a blue light, breaking up the silhouette of the fish and camouflaging them from any predator looking up. They looked at five juvenile V. mabahiss specimens to better understand how the fish used its light.

While the photophores varied in size, the researchers found that they all shared the same structure. The light is produced through a well-understood biochemical reaction, and the sophisticated composition of the photophores directs that bioluminescence into useful camouflage. “They have this thick pigment layer to block the light from entering the fish, reflective cells that amplify the light, and a lens that lets the light pass through,” said Clardy.

A small fish only known to the Red Sea, V. mabahiss lives deep underwater and is seldom encountered by people, so much so that it has no common name. The findings from this study will provide bedrock information for future researchers to study bioluminescence in fish. “Its rarity means that V. mabahiss may be difficult to collect for most researchers,” said Clardy “We hope to provide information that other scientists can use for the broader study of bioluminescence.”