Fragmentary Fossils Help Tell the Whole Evolutionary Story

Paleontological “twigs” from our fossil past can help us reconstruct branches on the tree of life

Picture a beautiful, sunny day in your neighborhood park. You are out for a stroll, taking in all the sights, sounds, smells, and sensations of being outside under a bright blue sky

As you amble along, your gaze drifts to the ground and you came across a twig, freshly fallen from the canopy of a huge, verdant oak tree overhead. You kneel to the ground, pick up the twig, and glance up at a thick assemblage of branches above you. You might wonder to yourself: what branch did this twig fall from? Could I find the exact spot on the branch it fell off? How would I go about finding that spot on the branch, and how confident would I be that this is the exact spot the twig belonged?

In a way, this is the type of problem paleontologists find themselves in whenever they discover an incomplete fossil. There is never a shortage of questions to ask: What species did this fossil fragment belong to? Who were that fossil organism’s closest evolutionary relatives at the time? How does this ancient organism relate to organisms alive today? While your stroll in the park described above might be an odd situation to commonly think about, placing these millions of fossil “twigs” on the giant tree of life is an exercise that paleontologists regularly carry out (in science-speak, this exercise is called “phylogenetics”). In fact, assessing evolutionary relationships of fossil organisms remains one of the great ongoing endeavors of paleontology and the study of fossils.

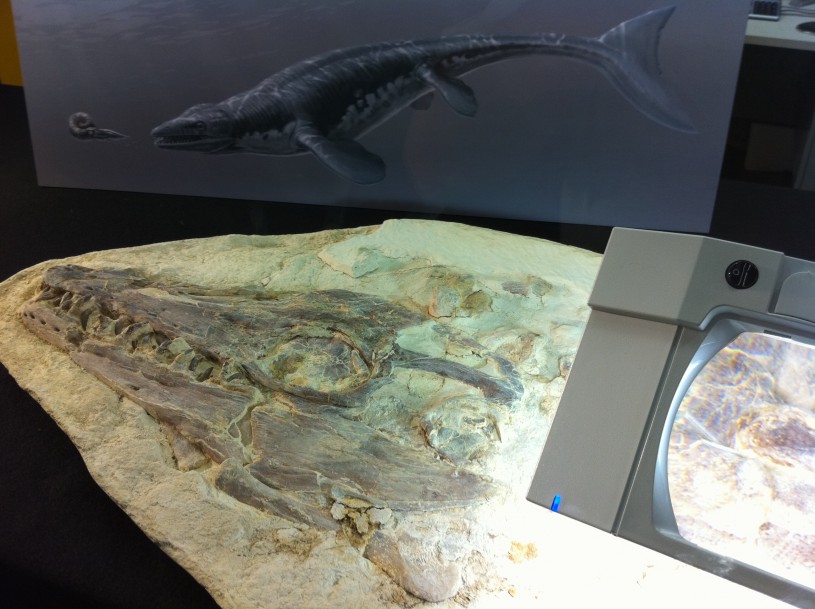

Fossils captivate our imaginations, especially the spectacularly preserved specimens that decorate the exhibit halls of museums around the world. These remarkably complete, rare fossils on display offer us some of the best clues regarding what life was like in our prehistoric past. But behind the scenes in museum collections lie vast treasure troves of valuable scientific information preserved in the less complete fossils that often never see the public eye.

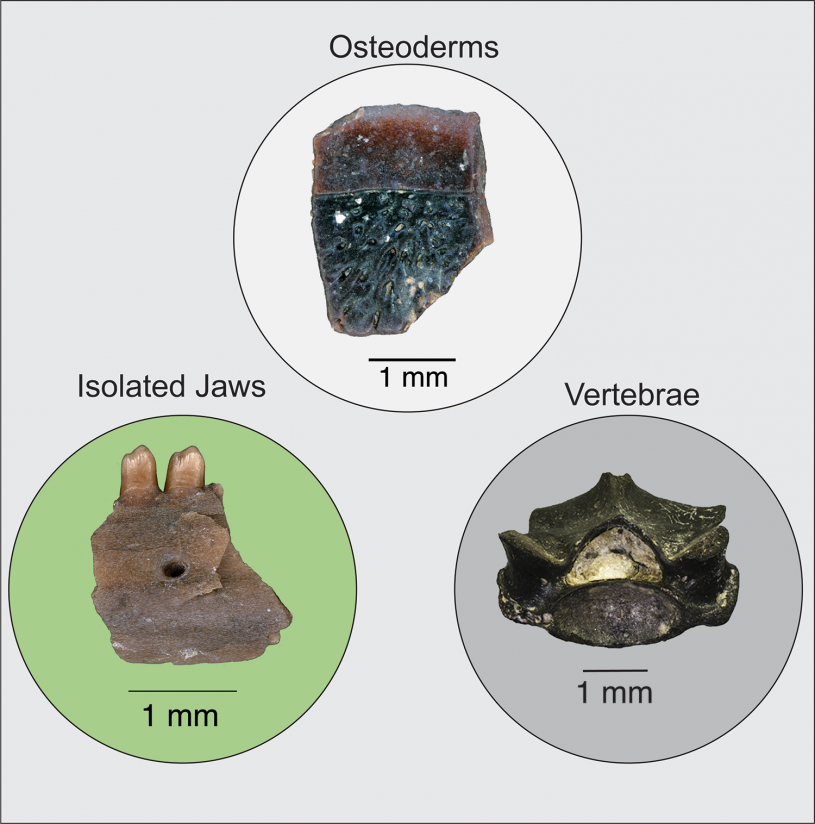

Although many of these behind-the-scenes fossils aren’t much to look at, they nevertheless have the potential to provide scientists with a wealth of biological, ecological, and evolutionary information to help us better understand the history of life on Earth. However, paleontologists are still trying to figure out how to best incorporate them into broader evolutionary biological studies, or whether to incorporate them at all.

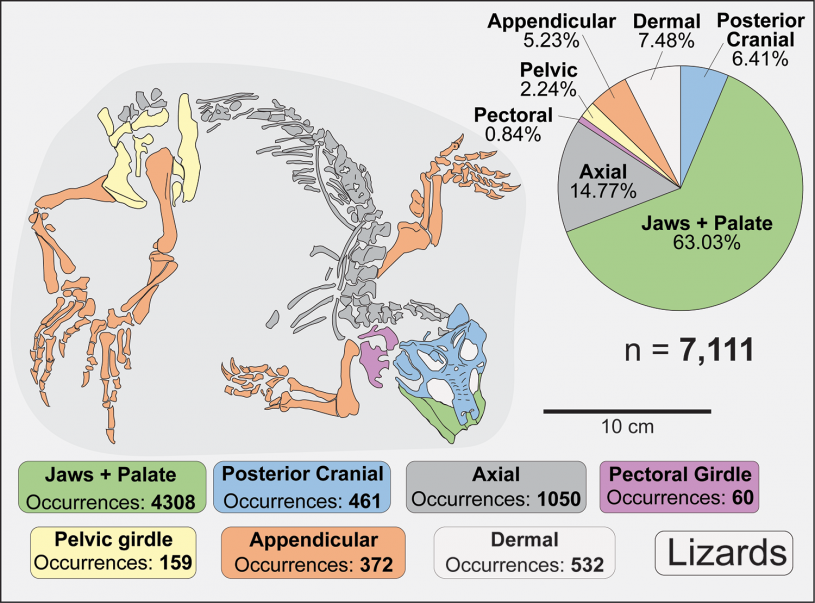

Our novel study tests the traditionally-held hypothesis that incomplete fossils (the majority of known extinct biodiversity) contain less reliable evolutionary information than their more complete counterparts. Using over 6,500 specimens from the museum collections-based fossil record of squamates (e.g., lizards, snakes, and their extinct giant marine relatives, mosasaurs), we found that certain parts of the skeleton (jaws, teeth, ribs, and vertebrae) make up most data available to us in museum collections, to the near exclusion of the rest of the skeleton. We use a series of phylogenetic comparative methods, metrics, and tests to show that this incomplete representation of the skeleton in the fossil record does not mislead our interpretations of evolutionary relationships of lizards, snakes, and their relatives.

What our study shows is that incomplete fossils can contain reliable phylogenetic information and that we can be more confident in our placement of these paleontological “twigs” on the tree of life. This is exciting, because results like ours increase the scientific value of incomplete specimens housed in museum collections, and allows us to include more of Earth’s extinct biodiversity as we continue to piece together the past. And the more complete our picture of the past is, the more capable we will be in accurately predicting and managing changes in today’s ecosystems as our planet continues to warm.

Read the article at Paleobiology here.