BE ADVISED: On Saturday, February 21, the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum will host the LAFC vs. Inter Miami soccer match. Kickoff is at 6:30 pm. This event will impact traffic, parking, and wayfinding in the area due to street closures. Paid parking for Prehistoric Fight Nights will be offered in the NHM Car Park at Exposition Blvd and Bill Robertson Ln. Please consider riding the Metro E (Expo) Line and exiting at USC/Expo station.

BE ADVISED: The Natural History Museum is not participating in SoCal Museums Free-for-All on Sunday, February 22.

History, Uncensored

Uncovering a history of censorship that threatened two of L.A.'s most iconic murals

Published September 3, 2024

By Zuhura McAdoo

Los Angeles is a city with a diverse history shaped by various multiethnic communities, including the Indigenous people who originally cultivated this land. The Los Angeles Chicano community is composed of Mexican-Americans with Indigenous roots that trace back to Spanish and Indigenous founders of Los Angeles in 1781. The Mexican Muralism Movement emerged in 1920 and would soon deeply impact generations of artists, particularly those who participated in the 1960s Chicano Movement in the U.S. West and Southwest. Murals became a powerful art medium embodying a unique art expression that allows for the documentation of a community’s essence by depicting its culture, history, and communal message. These murals also serve as a reminder of the people who were here before colonization, imperialism, and gentrification.

One Chicana artist who has been greatly influenced by both the Chicano Movement and the Mexican Muralism Movement is Barbara Carrasco. Perhaps one of Carrasco’s most monumental works is her mural titled L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective. As a local Chicana artist from Los Angeles, she learned at a young age that institutional racism would be an ongoing fight. Yet, she used her murals as a means of rebellion, expression, and historical documentation of marginalized peoples. In her works, Carrasco’s murals beautifully convey complex histories of oppression of marginalized communities within Los Angeles history while highlighting moments of celebration and iconic martyrs.

In the mural, Carrasco portrays the multiethnic history of Los Angeles through a series of vignettes that tell the stories of the city's past woven into the hair of la Reina de Los Ángeles (The Queen of Angels). Carrasco was originally commissioned by the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) in 1981. However, after seeing the mural's political message, the CRA decided not to reveal it to the public and asked her to remove 14 scenes that they deemed controversial. Luckily for Carrasco, she copyrighted her mural prior to this request, thus helping her win possession of her work and place it into storage.

At 26 years old, Carrasco had a bold spirit that understood the necessity of staying true to one’s morals. She recalls, “I remember being a little surprised that they would want to eliminate historical scenes of Los Angeles history. I was surprised and it took me a while to really grasp what was going on. And then I thought, immediately, I have to get my copyright on this. So I called up Senator Alan Sieroty, who wrote a bill protecting artists' rights via copyright. I had the nerve to just call his office and talk to him, and surprisingly, he answered the phone. So I immediately copyrighted the mural legally.” Thankfully, she was able to legally protect her work, which allowed her to have ownership of the mural. She jokingly mentioned that “ they [the CRA] tried to say I was an employee and therefore I could not copyright my work however, I realized I was a commissioned artist so technically I could copyright it. Looking back now, I was pretty bold and smart for a 26-year-old to say that and stand up for myself.”

Carrasco recognized her rights and refused to be erased or repressed. Her commitment to the truth and speaking truth never waned despite the scrutiny she faced. The repression she has faced has led to the fact that the mural has only been on display three times over the course of 40 years. Reassuringly, it will now be permanently on display beginning in September 2024 at the NHM new wing at NHM Commons.

América Tropical

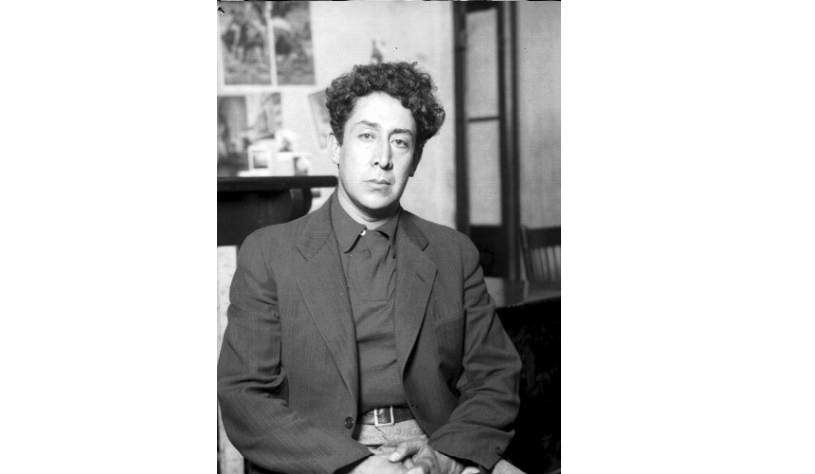

Mexican Muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974) is one artist who has had a significant impact on Carrasco’s work. Siqueiros is a monumental figure within the history of Mexican muralism. Siqueiros was one of the three founders of the modern school of Mexican mural paintings, also known as the Mexican Muralism Movement, alongside artists Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco.

Throughout his life, Siqueiros was involved in numerous labor and political organizations such as the Executive Committee of the Mexican Communist Party, the Latin American Trade Union Confederation, the League of Writers and Artists of Uruguay, and the National League against Fascism and War, among many others. Consequently, Siqueiros was a notable figure within Mexican art as an activist, academic scholar, and artist who greatly inspired generations of socially engaged artists through his radically bold depictions of Mexican and Indigenous culture.

According to Merriam-Webster, the term “whitewashing” means: “to whiten with whitewash” or “ to portray [(the past]) in a way that increases the prominence, relevance, or impact of White people and minimizes or misrepresents that of nonwhite people.” Both of the abovementioned definitions of the “whitewashing” term apply to how government officials treated Siqueiros's art on Olvera Street in 1931. As Olvera Street underwent a “revitalization” process, city officials sought to hire Siqueiros to create a mural that would appeal to prospective tourists. Siqueiros was initially instructed to create a mural with a “tropical theme, intended to evoke a jungle-like ambiance that reflected the lush, vibrant landscapes of Latin America.”

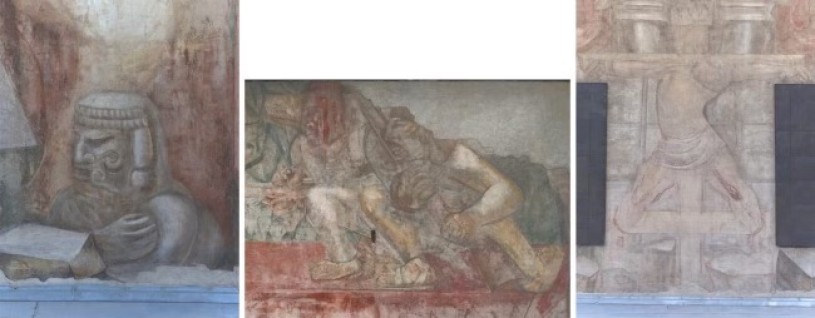

However, Siqueiros defied these orders and seized this moment as an opportunity to adhere to the theme through his critical lens, opting for a truthful depiction of Los Angeles history rather than a commercialized portrayal of Latin American culture. His vision of a tropical landscape completely jarred the public. The controversial image depicted was of an Indigenous subject crucified in the center of the mural, nailed to a double cross underneath an American eagle with wings spread wide. Historians believe that the figure represents the marginalized community being sacrificed for the sake of colonization. Also depicted in América Tropical are two armed revolutionaries whose weapons are aimed at the eagle, seemingly communicating that these marginalized communities should wage war and resist oppression.

This work served as a strong critique of American foreign policy, imperialism, and mistreatment of Mexican and Indigenous peoples in the United States. Many artists contributed to the mural, including Jackson Pollock’s brother, Charles Pollock. The mural was literally and figuratively whitewashed as government officials covered the mural with white paint to repress Siqueiros's message on the consequences of American imperialism on Indigenous and Mexican communities. This act of whitewashing functioned as yet another manifestation of the cultural erasure of the histories of oppressed peoples. Despite this attempt at repression, his work would continue to remind future generations of artists of the importance of preserving and expressing their cultural heritage.

This history is why feminist Chicana artist Barbara Carrasco chose to depict Siqueiros's mural within her own work, L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective. She dedicated a panel of L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective to Siqueiros América Tropical and titled it Whitewashing History. In our discussion, Carrasco recalled how she felt personally connected to Siqueiros's work after enlightening conversations with the late William M. Mason at the Natural History Museum. “I came here to this museum and talked to Bill Mason, who was a historian. And he just gave me access to all these photos and archives about the history of Los Angeles including the Siqueiros mural on Olvera Street. I learned they covered América Tropical two weeks after it was completed. I thought it was important for me to make a connection with a Mexican artist that came over here [to Los Angeles]. He could have just been a tourist but he decided to leave a political statement with this mural. I just respected him as an artist and as a human being, to show images that reflect the time period, and I think that’s what I was trying to do with this mural.”

Carrasco also noted, “When I was growing up I never once heard my history spoken in history classes. When I went to UCLA they never showed Mexican art—ever—in the art department, it was always European art. They never talked about the great artists of Mexico and Siqueiros is one of the great muralists.” She knew it was important for her to capture Siqueiros's legacy as a Chicana mural artist who uses powerful imagery as acts of resistance.

Carrasco had a great appreciation for the political messages in his murals as well as his technique. According to Carrasco, “The mural was showing the history of Mexico from the subject on the cross to the eagle which represents the U.S and the two revolutionary figures armed in the corner. Then, in the 1930s, Siqueiros was using an airbrush. They didn’t use a paintbrush”. The use of an airbrush during this time was a revolutionary technique that required much artistic skill and craftsmanship, which is why Siqueiros is highly revered. Carrasco also enthusiastically recalls learning that Siqueiros “didn't care about the money when it came to creating the mural. He cared about the subject matter and getting across a powerful message out like, the history of Mexico despite the backlash he would receive.”

As someone who also experienced censorship, Carrasco related to the struggles of having her work be taken from public view; yet she understood the importance of using your voice regardless of the repression she may have or continue to face. Carrasco’s respect and reverence for Siqueiros's work is clear in Whitewashing History, where she depicts Siqueiros in the foreground of Whitewashing History while he anticipates his mural to be covered in buckets of white paint.

Despite the undeniable truths that each artist’s work embodied, Carrasco and Siqueiros both suffered from whitewashing and erasure in Los Angeles as officials deemed their work too radical. The homonymous depiction of this whitewashing will now be permanently on display for future generations of artists to know of the significance of David Alfaro Siqueiros's first and last mural in the United States. His message will continue to live on as his legacy continues within Barbara Carrasco’s L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective.