How Los Angeles Moved Uncomfortably Close to Mountain Wildfires

A look at L.A.'s growth toward wildfires through historic images from the Seaver Center

Published September 25, 2023

In 1853 Los Angeles, a fire alarm was the sound of a pistol discharged in rapid succession, and it was up to neighbors to form a bucket brigade from the zanja (ditch). A city volunteer fire force did not officially form until 1871, and a paid fire department was established in 1885.

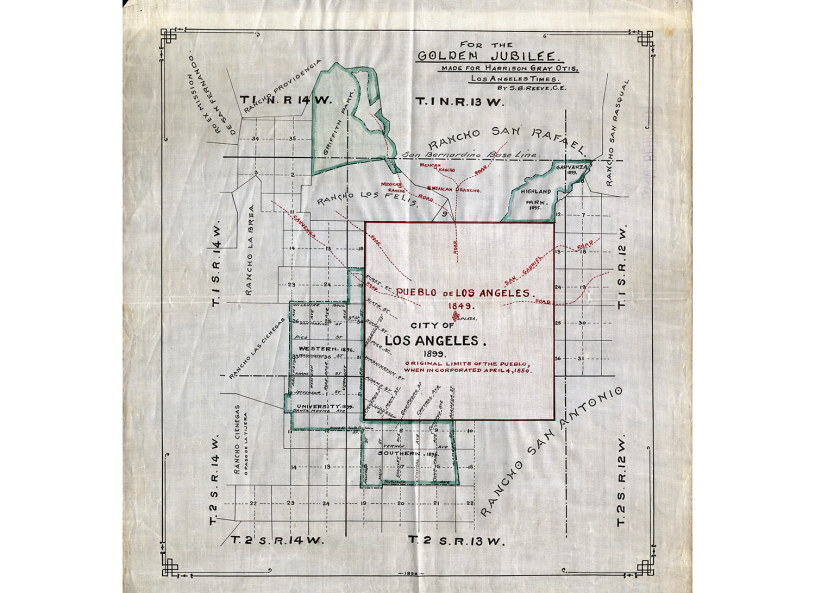

Any need by the townspeople to contend with cyclical fires in the mountains of Santa Monica, Santa Susana, or San Gabriel was a distant concern because of the stretches of uninhabited plains that laid in between–not to mention the lack of means to put out a fire. In 1850, the southwestern edge of the ciudad (city) sat near present-day Figueroa Street and Exposition Boulevard–imagine roughly the distance from the Natural History Museum to the Getty Center located at the periphery of the Santa Monica Mountains.

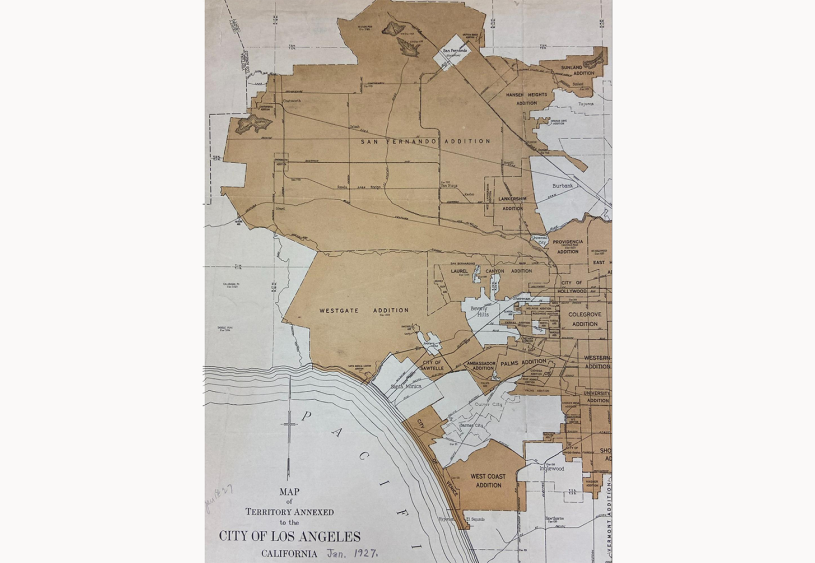

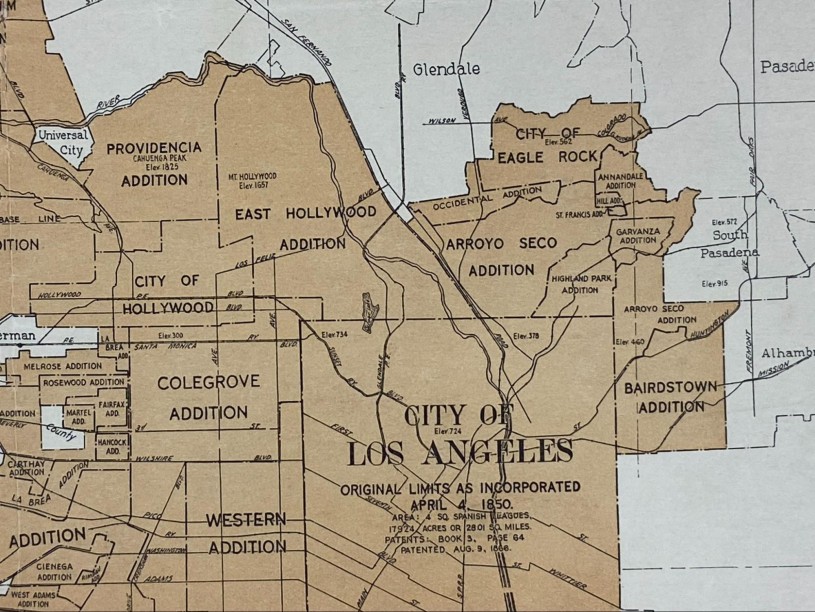

Newly hydrated thanks to the opening of the L.A. Aqueduct in November 1913, Los Angeles steadily annexed local towns. Brought into the municipal fold were vegetation-abundant foothills. The San Fernando Valley addition in 1915 and the Westgate (west L.A.) annex the following year increased city land by over 139,000 acres. Between 1926 and 1932, the Verdugo Mountains communities of Sunland, Tujunga, and Tuna Canyon were acquired.

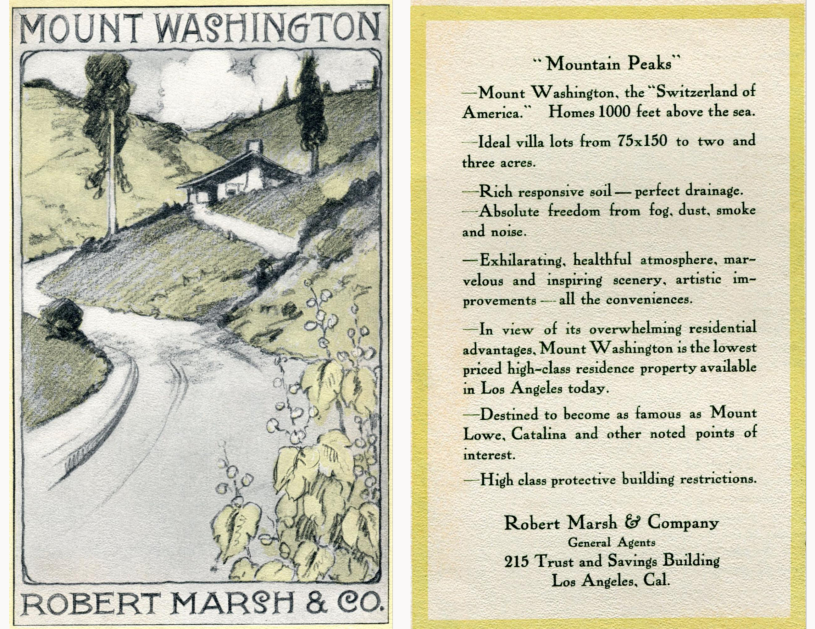

Mount Washington

Before the spike in annexations throughout the 1920s, the real estate firm Robert Marsh & Company was promoting Mount Washington, their subdivision in northeast L.A., as the “Switzerland of America.” A circa 1911 sales brochure promised lofty views, clean air, and good soil.

By the 1980s, Mount Washington was among the many hilly communities facing stricter standards for fire prevention. These measures came out of lessons learned from the fires of Bel Air in 1961, Chatsworth in 1971, and Baldwin Hills in 1985. Following the 1991 Oakland Hills Firestorm in northern California, Mount Washington was one of many areas relegated as a “very high fire hazard severity zone.”

Griffith Park

An earlier annexation in 1910 brought East Hollywood into the city of Los Angeles and included the area known as Griffith Park. On October 3, 1933, a small fire ignited there, possibly from debris. It escalated and harmed thousands of county welfare workers who were clearing brush at the time and also those who were called there to fight the fire. 28 persons died, and an additional victim succumbed two weeks later. Two young children were severely burned while at a play area. The tragedy struck during the depths of the Great Depression, and blame was laid on the lack of a broad prevention plan including the absence of fire-fighting equipment, fire hydrants, and the lack of sufficient trained fire personnel.

Santa Monica Mountains

In 1912 travel west beyond the city limits was along a county road leading towards settlements like the Rindge ranch in Malibu, the Bison outdoor motion picture set, and the neighboring towns of Beverly Hills and Sawtelle. That year in November a wind-swept fire in Malibu raged for five days and threatened the above establishments. Los Angeles happened to be gearing up for its fourth international aviation meet on Thanksgiving Day, and among the competitors was Tom Gunn, the Chinese-American aviator. Newspapers reported that while biding time, he flew over Malibu to test the feasibility of transporting firefighters and adapting planes for protecting forests.

Two government entities, city and county, oversaw fire matters. The 1912 calamity occurred under the watch of the County Fire Warden. The Los Angeles County Fire Department was established in 1923. By 1924 the City Fire Department added a Mountain Patrol—the human arsenal to watch over the Santa Monica Mountains. During a disaster, devastation blurred boundaries, and the Mountain Patrol responded to brush fires in the County jurisdiction such as in the community of Topanga. In the late 1960s the Patrol was supplanted by helicopters—and the establishment of four fire stations along Mulholland Drive.

Courtesy of the Seaver Center for Western History Research

Centerfold Map from Marblehead Land Company Brochure, ca. 1939

Despite three Malibu firestorms in 1930, 1935 and 1938, real estate development pressed on.

Courtesy of Seaver Center for Western History Research

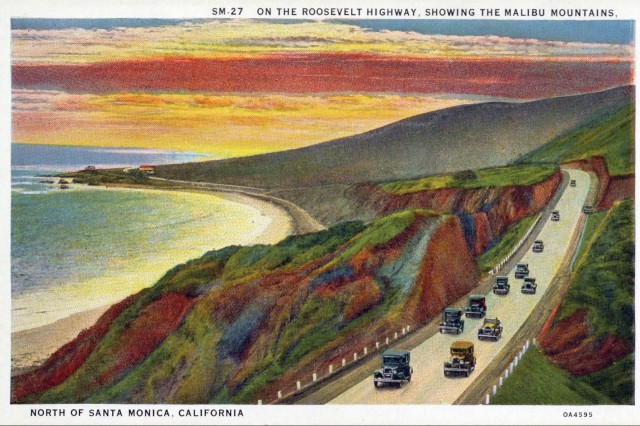

A paved Roosevelt Highway (which would become Pacific Coast Highway) offered ease of access by automobiles through the Malibu coast.

1 of 1

Centerfold Map from Marblehead Land Company Brochure, ca. 1939

Despite three Malibu firestorms in 1930, 1935 and 1938, real estate development pressed on.

Courtesy of the Seaver Center for Western History Research

A paved Roosevelt Highway (which would become Pacific Coast Highway) offered ease of access by automobiles through the Malibu coast.

Courtesy of Seaver Center for Western History Research

San Gabriel Mountains

Much like the periodic and ceaseless environmental chaos on the coast, perpetual fires inland within the San Gabriel Mountains adversely impacted its foothill cities. One such event, the Mt. Lukens fire of November 22, 1933, lasted four days. The fire would have been just one of many to occur throughout time had it not been followed in a little more than one month by a New Year’s Day cloudburst that unleashed a deluge, floods, and rockslides. The burned and balded terrain left indefensible the communities of Flintridge, La Canada, La Crescenta, Montrose, and Tujunga, and also affected were Burbank and Glendale.

Images courtesy of Arthur C. Ostermann and the American Legion Verdugo Hills Post 288

Fire north of Montrose-La Crescenta, November 1933.

Images courtesy of Arthur C. Ostermann and the American Legion Verdugo Hills Post 288

Fire north of Montrose-La Crescenta, November 1933.

1 of 1

Fire north of Montrose-La Crescenta, November 1933.

Images courtesy of Arthur C. Ostermann and the American Legion Verdugo Hills Post 288

Fire north of Montrose-La Crescenta, November 1933.

Images courtesy of Arthur C. Ostermann and the American Legion Verdugo Hills Post 288

Replanting After Wildfires

Helicopters were again on scene in the aftermath of fire damage to facilitate the government practice of reseeding the barren hills with species like ryegrass and Blando brome. Instances reported by the San Fernando Valley Times newspaper included seed drops in 1957 and 1962 within a handful of months following major fires around Sylmar, Kagel Canyon, and the Verdugo Mountains.

Intents were twofold, as Daniel Feldman, Senior Manager of Horticulture at NHM, observed. They chose “to reseed these areas with what are basically pasture species for livestock. Both grasses are fast growing and germinate quickly, and it seems they were primarily trying to prevent soil erosion in the rainy season by quickly vegetating the bare ground."

Courtesy of Seaver Center for Western History Research

Aftermath of New Year’s Flood January 1, 1934

Floods frequently follow wildfires that burn away vegetation, leaving behind scorched earth unable to absorb water.

Courtesy of Seaver Center for Western History Research

Aftermath of New Year’s Flood January 1, 1934

Courtesy of Seaver Center for Western History Research

Aftermath of New Year’s Flood January 1, 1934

1 of 1

Aftermath of New Year’s Flood January 1, 1934

Floods frequently follow wildfires that burn away vegetation, leaving behind scorched earth unable to absorb water.

Courtesy of Seaver Center for Western History Research

Aftermath of New Year’s Flood January 1, 1934

Courtesy of Seaver Center for Western History Research

Aftermath of New Year’s Flood January 1, 1934

Courtesy of Seaver Center for Western History Research

As the environmental sciences have advanced through the years, replanting practices are being reconsidered. Feldman notes “There are many native species that could have been chosen, and I would guess the result was widespread replacement of many native species that were in those canyons and hillsides, many of which have evolved to be adapted to fire. There are many types of ryegrass, even a couple of native species. Blando brome is non-native and is invasive in some situations, though it is still sold in California as an erosion control plant. In the greater scheme of things, it seems like using these fast-growing (and fast drying) grasses instead of fire-adapted native species may have made the areas more prone to fast-moving wildfire, even into the present day.”

Mount Wilson

A climb to the summit of Mount Wilson can be done along the tough and difficult Mount Wilson Trail that was established long before the Mount Wilson Observatory was constructed. Though the trail followed an ancient path, its name is attributed to Southern California settler Benjamin “Benito” Wilson. In 1864 he appointed his workers to clear a trail so that cedar and pine could be logged. The place names of the prominent Wilson, who died in 1878, have outlasted the short-lived venture.

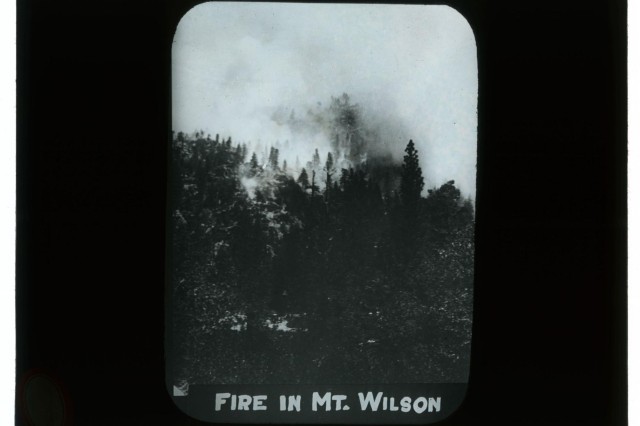

The architects of the 1904 observatory wisely built defenses against the inevitable pyro threats, including a concrete water reservoir and other concrete and steel fortifications. There have been many close calls through the years.

Courtesy of Seaver Center for Western History Research

Fire seen from Pasadena

Courtesy of Seaver Center for Western History Research

Slide depicting Mt. Wilson fire

P-230 Hearne Lantern Slide Collection, ca. 1880s-1930s

1 of 1

Fire seen from Pasadena

Courtesy of Seaver Center for Western History Research

Slide depicting Mt. Wilson fire

P-230 Hearne Lantern Slide Collection, ca. 1880s-1930s

Courtesy of Seaver Center for Western History Research