BE ADVISED: On Saturday, February 21, the Natural History Museum will be closing at 4 pm. The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum will host the LAFC vs. Inter Miami soccer match, with kickoff at 6:30 pm. This event will impact traffic, parking, and wayfinding in the area due to street closures. Please consider using public transportation or rideshare.

BE ADVISED: The Natural History Museum is not participating in SoCal Museums Free-for-All on Sunday, February 22.

The Jonker Diamond: A Giant Gem of Many Facets

Explore the human and natural history of the Jonker I Diamond

Published December 1, 2023

The story of the Jonker I Diamond is appropriately big—and astonishingly deep. It starts 300 miles straight down into the Earth, about a billion years ago.

“As you get these larger and larger diamonds, they tend to form deeper and deeper in the Earth. And that's not always 100% true, but it mostly holds true for the vast majority of the diamonds. So we're talking like 300 miles—from L.A. to Phoenix. That's the depth that we're talking,” says Dr. Aaron Celestian, Curator of Mineralogy at NHM.

Most of Earth’s diamonds—that is diamonds that formed inside our planet as opposed to the ones riding around meteors or possibly raining on the surface of Jupiter due to the pressure—were created by extinct kimberlite volcanoes that stopped erupting over 70-million-years ago. The incredible heat and pressure of these eruptions can just as easily destroy a big baby diamond. Even though these diamonds are around a billion years old, they have to reach the surface pretty darn quick—in about 15 minutes—or no diamond.

“If there's any pause in the volcanism that's bringing that up, then it can get redisolved,” says Celestian. So even though diamond is thought to be surprisingly common in our universe, big Earth diamonds like the Jonker are extremely rare. When it was first discovered, the Jonker was thought to be part of the biggest diamond ever discovered, the 3,106-carat Cullinan Diamond.

“This is a glass replica of the Cullinan, and it has this really flat surface right here. And this is thought to be a cleavage plane where the crystal may have broken during its ascent to the surface of the Earth, and nobody could figure out where the other part was.”

Its 1905 discovery had brought hordes of prospectors to South Africa in the belief that the Cullinan was only part of a larger undiscovered stone based on its distinct planes. vv

Johannes Jacobus Jonker was one of those prospectors looking for the hypothetical other parts of the Cullinan Diamond, but hadn’t found much in 18 years of mining until a 1934 rainstorm when his youngest son found the 726-carat diamond. The gem would become a global sensation.

“But the Jonker diamond, when it was found, also had a very large, flat plane on it as well. So people thought that they were attached together at one point,” says Celestian.

This possible connection and its own massive size (and later a media-savvy gem dealer) made the Jonker’s discovery a global sensation. First purchased by Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, in 1935 New York diamond dealer Harry Winston purchased the uncut gem for £150, 000. Winston had the diamond shipped by registered mail for 64 cents—uninsured—from South Africa to New York City and opened the unassuming package in front of a crowd of eager reporters, the first in a series of PR flashes. After touring the stone through every major city in the United States—and commissioning photographs with celebrities like Shirley Temple, Winston chose Lazare Kaplan to cut the giant diamond.

Olive Oil and Diamond Dust

At the time, the Jonker was the largest diamond ever cut in the United States. It took six months to a year to properly plan the cut of the rough diamond. Kaplan took so long to plan because despite being the hardest natural substance on Earth, even diamonds have weaknesses.

“The advantage of cutting it by hand is that these are inherent planes of weakness. People think diamonds are indestructible material, but they're very destructible, if that's a word,” says Celestian. Diamonds are split along the grain like logs of wood, and figuring out the directional molecular structure is key to cutting a rough gem. Through meticulous study, diamond cutters can also eliminate those planes of weakness and ensure the stones produced won’t shatter on impact.

Hand-cutting can make for stronger stones, but it does carry risks. “The disadvantage is that if you miss, then you have a much smaller piece to start with,” says Celestian. “He could have hit it along the wrong plane or at the wrong angle, and it'd be another fracture going off in a different direction.”

After precisely marking the angles on the massive gem in India ink, Kaplan first worked a groove into the hard surface of the diamond to best ensure it would break according to his calculations. His tools were coated with olive oil and diamond dust to help the blades find purchase in the incredibly hard surface. After aligning the blade into the groove, a sharp blow splits the stone (and presumably everyone exhales).

Kaplan’s calculations (and cutting) proved flawless, producing 13 gems, the largest of which became the emerald cut, 142.90-carat Jonker I Diamond, considered to be the most perfectly cut gem in existence by some. What makes a cut perfect? Maximizing brilliance.

King Farouk of of Egypt (and Sudan, Sovereign of Nubia, of Kordofan and of Darfur), pictured here with Franklin D. Roosevelt, purchased the Jonker I in 1949 as part of his growing collection of very nice things but could hold onto it for three years before a military coup left him in exile, and the gem seemingly lost.

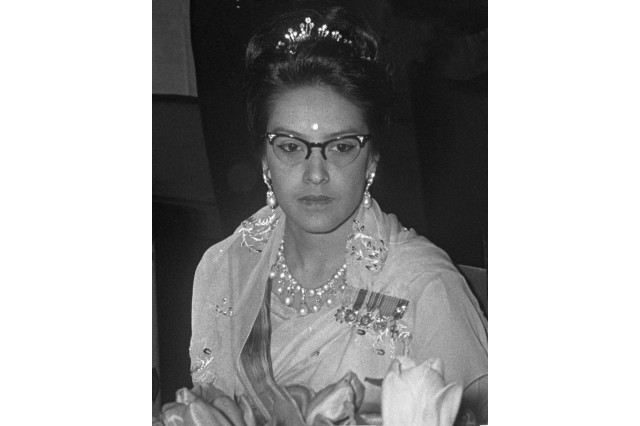

The Jonker I turned up again in royal hands, this time Queen Ratna of Nepal who owned it until 1977 when it was purchased by an anonymous buyer in Hong Kong. Notably, whether it has ever been set—and exactly how Queen Ratna acquired it—is unknown.

1 of 1

King Farouk of of Egypt (and Sudan, Sovereign of Nubia, of Kordofan and of Darfur), pictured here with Franklin D. Roosevelt, purchased the Jonker I in 1949 as part of his growing collection of very nice things but could hold onto it for three years before a military coup left him in exile, and the gem seemingly lost.

The Jonker I turned up again in royal hands, this time Queen Ratna of Nepal who owned it until 1977 when it was purchased by an anonymous buyer in Hong Kong. Notably, whether it has ever been set—and exactly how Queen Ratna acquired it—is unknown.

Celestian explained that the brilliance of a stone is partially governed by its refractive index—a number measuring how fast light travels a transparent object. “The higher the refractive index, the more brilliant the stone can be,” said Celestian. “Diamond has a fairly high refractive index, but it doesn't just stop with that.”

“You have to cut it so that the rays of light have a maximum amount of bouncing within the stone. And every time the ray of light bounces off of a facet and comes out off the top of the stone, which is the table, the more times it bounces, the more opportunity light gets to refract, gets to bend and split apart, just like a rainbow,” said Celestian. More bounce means more bling.

The same flawless beauty that made the Jonker Diamond so valuable on the gem market clouds its exact origins and makes it less valuable for researchers like Celestian. “There's very little geology that can be done with this particular diamond because it doesn't have inclusions in it,” Celestian said. “Inclusions would tell us what sorts of other things are happening in a deep mantle, but this is so clean and colorless that there's really no information.”

Their tightly compressed, rigid structure lets diamonds carry minerals that would immediately dissolve if exposed to conditions above ground. These mineral inclusions like the recently discovered davemaoite would be completely inaccessible without diamonds. Similarly, gases and liquids trapped inside diamonds would immediately dissipate without their pressurized diamond containment. The Jonker Diamond’s geologic past is obscured by its perfect clarity.

What we’re left with is the fruit of a billion years—the movements of mountains, volcanoes, and the painstaking efforts of humans—a nearly perfect concentration of Earth’s brilliance.

The Jonker I is currently owned by Ibrahim Al-Rashid, who loaned the diamond to NHM for this exhibition.