BE ADVISED: On Saturday, February 21, the Natural History Museum will be closing at 4 pm. The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum will host the LAFC vs. Inter Miami soccer match, with kickoff at 6:30 pm. This event will impact traffic, parking, and wayfinding in the area due to street closures. Please consider using public transportation or rideshare.

BE ADVISED: The Natural History Museum is not participating in SoCal Museums Free-for-All on Sunday, February 22.

The Migration of the Lincoln Heights Whale

As modern whales make their annual journey across the ocean, discover one whale’s 10 million-year journey through time from Flat Top Hill to L.A. Underwater

Published February 7, 2024

Around 11 million years ago, the Lincoln Heights Whale took its last dive, descending to the ocean floor of the prehistoric Pacific. It would not have been a graceful descent—the fossil’s positioning suggested it landed belly up—but it was still uniquely impressive. The ancient whale would finally surface 500 feet above and about 20 miles inland from the shores of our modern Pacific.

At 32 feet, Mixocetus elysius was a bit larger than some of the other ancient baleen whales it swam alongside during the Miocene epoch, and its watery world was full of wonders: two kinds of sperm whales, birds with wingspans of up to 20 feet (and teeth), a smattering of non-tusked walruses, gigantic leatherback turtles, the last of the peculiar aquatic mammals we call desmostylians, and a terrifying 40-foot-long shark Megalodon.

“It was a very mixed fauna of marine mammals that includes close relatives of things that are fairly common like harbor porpoises and true dolphins and things that are more like the northern fur seal, but then there are outliers that are either completely extinct or are found in completely different regions,” says paleontologist Dr. Jorge Velez-Juarbe, Associate Curator of Marine Mammals at NHM.

“There was an extinct relative of the Chinese river dolphin with a really long snout specialized for catching fish by just moving the head sideways and kind of snapping around a school of fish; walruses, which are now more common around the Arctic Circle; and relatives of narwhals and belugas much farther south than we know they are now.”

Mixocetus swam with these other fantastic beasts deep into what is now inland Los Angeles when the shore touched Chino and San Dimas, while hilly regions like the Santa Monica Mountains and Palos Verdes were flat sea beds.

We can’t say what killed the Lincoln Heights Whale—there are no tell-tale Megalodon teeth in its skull, vertebrae, or shoulder bones—but its body nestled in the land that would become its namesake neighborhood, and powerful geologic forces would raise the bones into Lincoln Heights’ Flat Top Hill.

Plumbing Deep Time

By January 22, 1931, marine sediments from the ocean floor had become the mountains and hills of Los Angeles. Pushed up to these heights by geologic forces over millennia, the fossilized bones miraculously survived millions of years of mountain-making. In the intervening years, giant sloths, mammoths, and mastodons would thrive and perish from the region, glaciers would carve up the former ocean floor, and Mixocetus would wait, mostly undisturbed until plumber F.W. Maley started digging a trench to irrigate a planned orchard in the slopes of Flat Top Hill.

"I was digging and came upon a rock that looked like a vertebra. I dug around a little and saw some more and knew I had found something,” said Maley I have visited the museum on many occasions and I knew I had something. So I called them up and there it is."

Just as the geography and wildlife changed drastically during that final dive, the Los Angeles area has undergone waves of transformation. As the oldest suburb of L.A., Lincoln Heights has echoed those changes, and (since it rose from the ocean depths) Flat Top Hill has offered a 360-degree view of those momentous changes.

As one of the few green spaces in Lincoln Heights, Flat Top Hill represents a connection to the natural world and the ancient world through the Mixocetus’ discovery. While their habitats quickly vanish beneath the pavement, Flat Top plays an important role providing modern wildlife a corridor E. Debs Regional Park. It’s also an important piece of nature for locals to enjoy in a city with few other access points. As the region continues to urbanize, Eastside residents have organized to protect Flat Top. The residents of Lincoln Heights recently defended their historic hill in court, preserving the stretch of the wildlife corridor for now. Long before the discovery of Mixocetus, the Kizh/Gabireleño tribe considered it sacred land, and this reverence might ultimately preserve the site going forward, offering legal protection from further development.

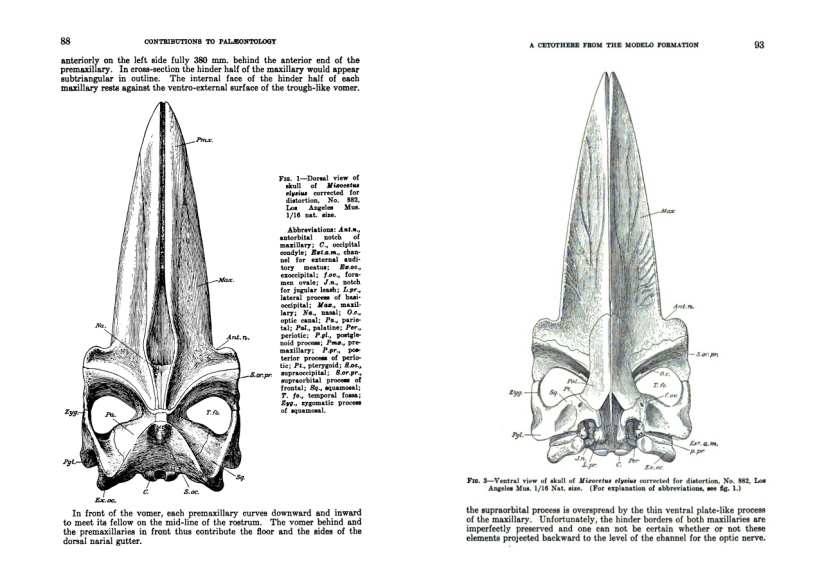

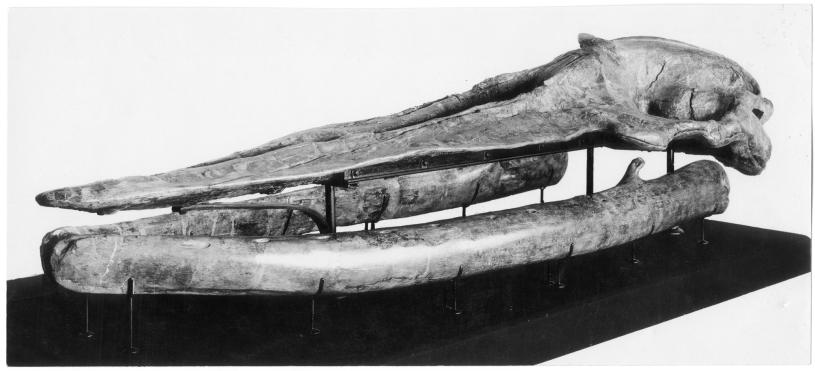

Encased in a plaster jacket, 8 feet and around 3,000 pounds of fossil whale and earth were hoisted out of the 9-foot pit, and Mixocetus surfaced in the Holocene (the Anthropocene started in 1950 when the dramatic increase in human activity really got going). Twenty-two vertebrae (five cervicals, twelve thoracics, and five lumbar), the left shoulder blade, the skull, and both lower jaws (baleen whales have a joint between their lower jaws to engulf as much water—and krill—as possible) were ultimately recovered from Flat Top and brought back to the Museum where Henry Wylde in the Vertebrate Paleontology Department would go to work preparing the gigantic fossil—cleaning off the sediment, fusing the broken fossils with glue and shellac, building al casing that would make more preparation possible as well as the steel and wooden platform that would keep the large but delicate skull aloft. Future director of the Smithsonian and whale expert Dr. Remington Kellogg studied the fossil specimen and wrote up a paper describing it as a new species, naming it Mixocetus, denoting a mixture of whale characteristics and elysius, referencing the Elysian Park Sandstone Member of the Modelo Formation.

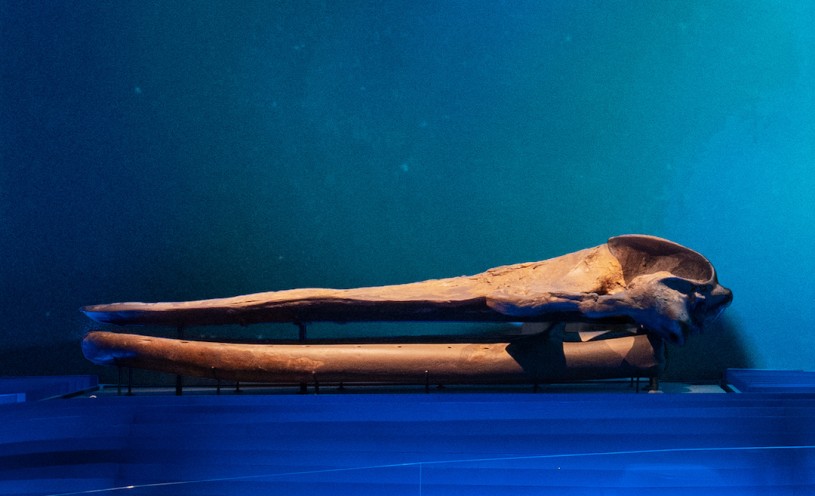

The Lincoln Heights Whale would become a favorite fossil at the Natural History Museum from the 1930s onward, on display in the Hall of California Fossils. But at some point, both the Hall and the whale would no longer be a part of the Museum’s displayed collection until 2022.

Under the Age of Mammals

Museums have their own evolutionary tracks, and institutional change eventually submerged the Lincoln Heights Whale again, this time in the basement. While the Museum welcomed updated halls and exhibitions, Mixocetus lingered at the bottom among other large fossils, even as the Age of Mammals—with its own incredible marine creatures, some of whom may have shared the Miocene sea—sprung up above it.

Vertebrate Paleontology Senior Preparator Alan Zdinak played a key role in resurfacing Mixocetus once again in the Anthropocene to take center stage in the temporary L.A. Underwater: The Prehistoric Seas Beneath Us exhibition. But first, the 1,500-pound base and skull would have to make it out of the basement to the special exhibition hall.

Opting for the fastest (if bumpiest) route, Museum staff moved the skull past collections of segmented worms (polychaetes), into the gravelly paths of the Nature Gardens and the Bird Viewing Platform.

“We had a little army of people to wheel it on this lovely new cart, and we laid down sheets of plywood to smooth the road, kept running around with a new sheet of plywood, and then down that slope going down toward the Otis Booth Pavilion,” said Zdinak. “That was the hairiest part of the whole thing, but we got it inside and upstairs.”

The massive whale skull would have to make its way to the Vertebrate Paleontology collections room on Level 4 for careful preparation—and restoration—before it could return to public view. During its most recent submergence, views on how to display fossils had evolved as well. While earlier displays might have emphasized the illusion of a complete, unbroken fossil, Zdinak, and the Exhibits team wanted to highlight the cracks and knicks that almost always accompany big fossils.

Photo by Juliet Hook

Vertebrate Paleontology, Exhibits, Operations, and Conservation staff help the Lincoln Heights Whale begin its ascent from collections storage

Photo by Tania Collas

Mixocetus elysius turns a corner, highlighting the difficulty in moving a whale-sized fossil in human-sized spaces

Photo by Tania Collas

A makeshift road made things a little less bumpy for the Lincoln Heights Whale's first trip outside in more than half a century, a journey made possible by Vertebrate Paleontology, Exhibits, Operations, and Conservation staff members.

Photo by Juliet Hook

Vertebrate Paleontology preparators get to work restoring Mixocetus elysius for a starring role in L.A. Underwater

1 of 1

Vertebrate Paleontology, Exhibits, Operations, and Conservation staff help the Lincoln Heights Whale begin its ascent from collections storage

Photo by Juliet Hook

Mixocetus elysius turns a corner, highlighting the difficulty in moving a whale-sized fossil in human-sized spaces

Photo by Tania Collas

A makeshift road made things a little less bumpy for the Lincoln Heights Whale's first trip outside in more than half a century, a journey made possible by Vertebrate Paleontology, Exhibits, Operations, and Conservation staff members.

Photo by Tania Collas

Vertebrate Paleontology preparators get to work restoring Mixocetus elysius for a starring role in L.A. Underwater

Photo by Juliet Hook

“For fossils on exhibit, the current philosophy is to paint reconstructed parts with a single color that is not trying to hide that there’s reconstruction but is also not distracting from the specimen,” said Zdinak. “I think it gives visitors insight into the realities of paleontology.” While choosing a single color that could tie almost a century of preparation together was hard, it’s difficult to argue with Zdinak’s results.

Zdinak and NHM’s Exhibitions team returned the Mixocetus to display complete with an animated reconstruction that puts the Lincoln Heights Whale back in the water for visitors. It’s a singular display, not just in terms of artistry.

While it was uncovered almost a hundred years ago, there has never been another of its kind discovered in the fossil record. Mixocetus elysius is a holotype, the specimen that researchers use to describe a whole new species. The story of its fossilization and discovery is a testament to time and change, and the improbability of any remnant of our ancient past surviving to our present day. There were any number of Mixocetus sharing the sea, but we’ve only ever found this one, and any other specimens might be lost to the oceans of time.

It also speaks to how natural history museums empower the people who visit them. F.W. Maley was a plumber—not a professional scientist of any kind—and if he hadn’t been an avid museum-goer, the Lincoln Heights Whale might have never surfaced again after that descent 10 million years ago.

“This city as a whole is so large, it's so dynamic, that when we also look into the fossil record, we see that instead of being large, it's deep. It's a deep-time component, going back to the last 100 million years,” says Velez-Juarbe. “The diversity, not just at specific points in time but over those 100 million years of history, is kind of like the diversity in Los Angeles. We can think of the demographics of the city as this whole combination of people from multiple places around the world, kind of like the marine environments during the time the Lincoln Heights whale was alive. We have things that we're familiar with, but some things nowadays are found somewhere else but they used to be here. It was almost kind of like the city. Kind of like an ancient melting pot in some ways.”