BE ADVISED: The Natural History Museum is not participating in SoCal Museums Free-for-All on Sunday, February 22.

Pop Goes the Museum

The Academy Awards noms will be announced this month, but we’ve already got our Oscar winners.

Published January 3, 2023

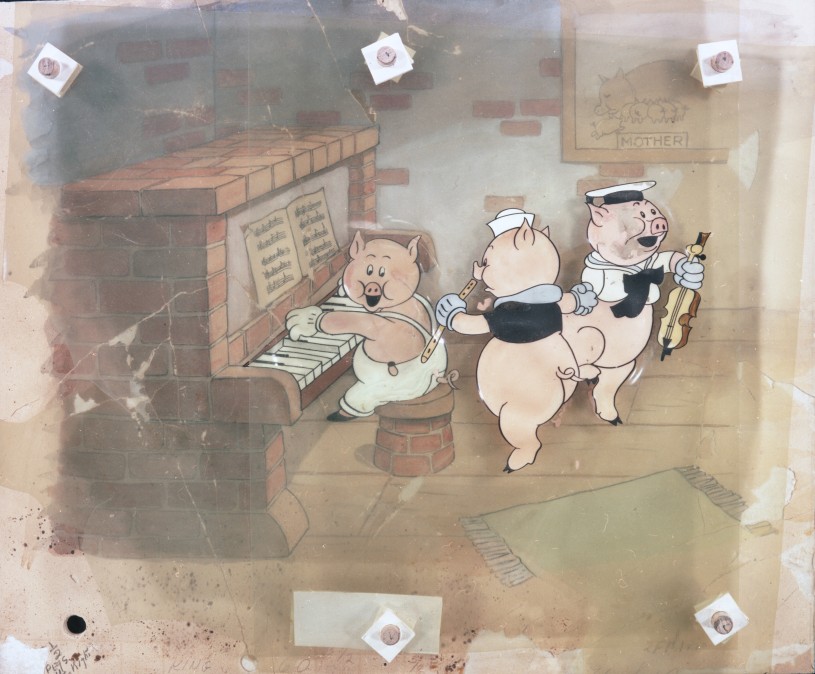

In 1931, Honorary Curator, Earl Theisen, approached animator and studio chief Walt Disney requesting materials for a motion picture hall he was developing for the then-named Los Angeles County Museum in Exposition Park. Disney generously made a number of donations over the next nine years, including animation art from his movies which featured mice, pigs, flowers, and trees as the stars.

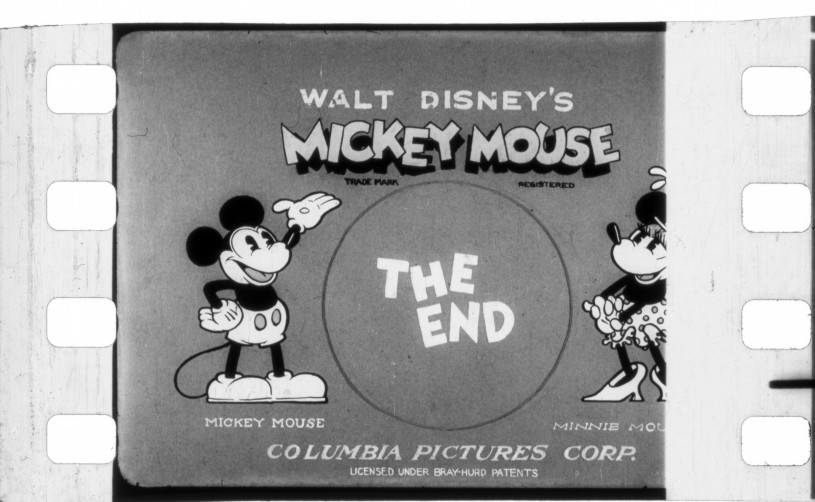

The film frames pictured below, which are not on display in the museum, make up just a fraction of NHM's History Collection.

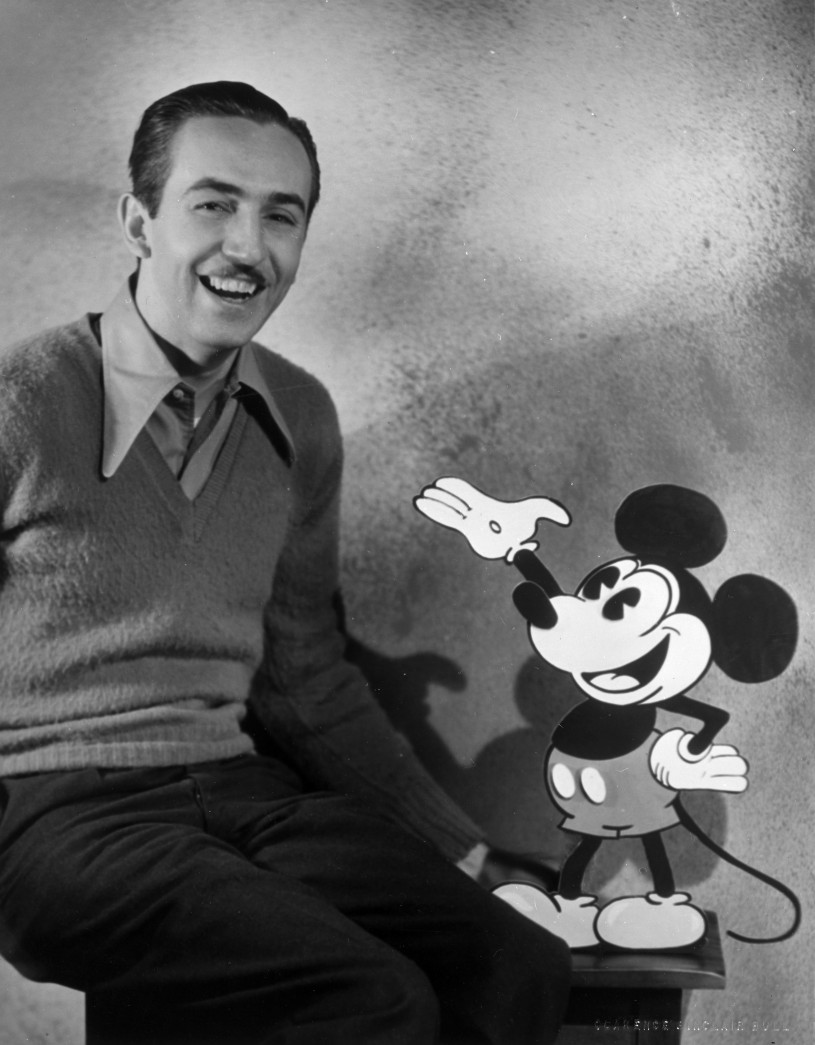

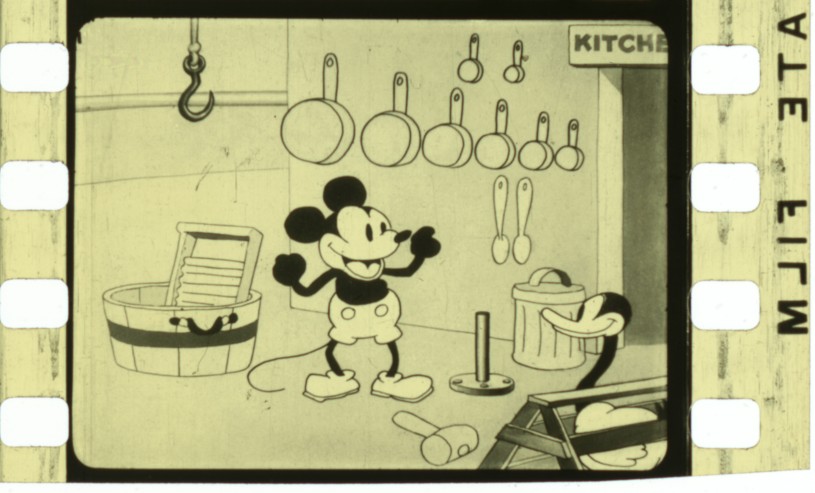

Beth Werling, the Collections Manager for NHM’s History Department, has an encyclopedic knowledge of our Hollywood collection—Oscar lore, and animations, in particular. She recounts that Disney had several failed animation ventures behind him when he decided to once again strike out on his own in 1928.

“When Disney notified Universal Studio that he was terminating his contract, he assumed he would be able to take his animated creation, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, with him,” Werling says. (The studio informed him otherwise; the character was under copyright.) “Disney had to develop a new character quickly, thus Mickey Mouse was created in a desperate gamble to launch the new Disney Studio.”

While Disney dominated the Academy Awards' Best Short Subject: Cartoon field, winning every year from the category’s inception in 1932 through 1940, no Mickey Mouse cartoon ever nabbed an Oscar. Disney was granted an Honorary Oscar in 1932, however, for inventing the ebullient rodent. Mickey Mouse remains the Disney Corporation’s trademark character, nearly 50 years after his creator’s death.

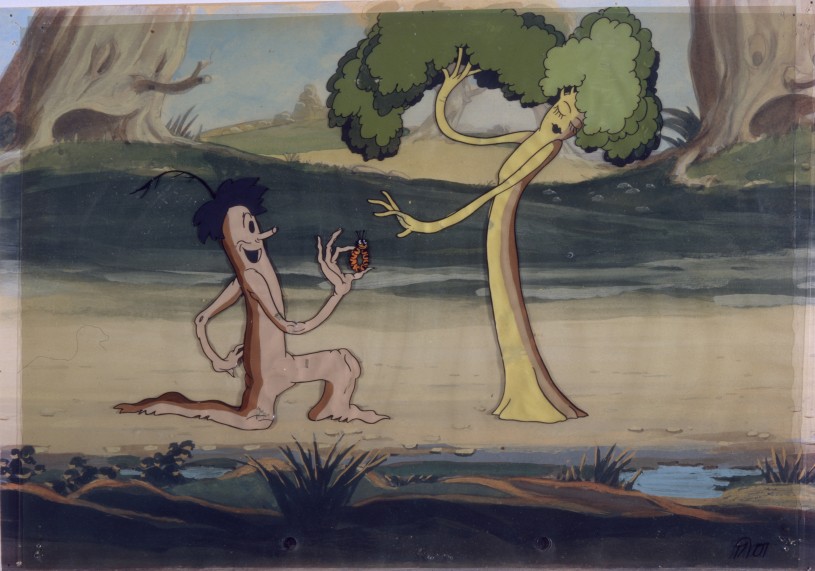

Flowers and Trees, Oh My

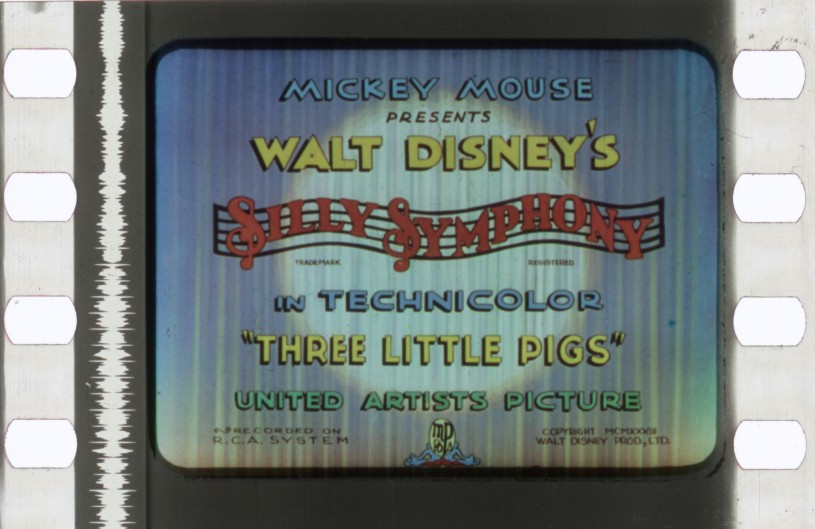

Flowers and Trees—part of the studio’s prestigious Silly Symphony series—was a commercial and critical success, winning Disney his first Academy Award, also the first Academy Award for Best Cartoon Short Subject.

Films produced as part of the Silly Symphony series won the first eight Oscars for Best Cartoon. Werling says Disney’s staggering number of statuettes and professional accolades are due, in part, to his imperative to continually push technological boundaries. Flowers and Trees was the first film to employ three-strip Technicolor.

The then-History Department Curator Theisen amassed a large collection of film clips—or frames—documenting such movie-making milestones. For instance, in the category of sound, the frames show Disney’s switch from one type of soundtrack (called variable density, seen by the lines seen on the left of the frame) of the Powers Cinephone to the audibly superior RCA Photophone. Although at the cutting edge when it came to color, Disney had lagged behind in the sound department.

Little Pigs, Bad Wolf

A major contributing factor to The Three Little Pigs winning an Oscar was “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?,” the first hit song, originating from a cartoon. The lyrics resonated with the American public, who heard it as a fight song with the Big Bad Wolf representing the Great Depression. Pinto Colvig, who provided the voice for the Practical Pig, donated a copy of the song’s lyrics in his handwriting.

When Walt Disney walked on stage at the Ambassador Hotel in March 1934 to accept the Academy Award for The Three Little Pigs as Best Cartoon, it was the second time in two years he had won. His acceptance speech this time, however, made Academy history because he referred to the statuette as “Oscar.” This was the first time the motion picture industry’s nickname for the award was publicly acknowledged.

Today, the Oscar is an iconic symbol recognized around the world with a monetary value attached, but in the early days of the Academy, it was not treated with the same respect. Academy President Frank Capra authorized plaster replicas, the same size as the originals and painted gold to be used as table decorations at the annual Academy Awards dinner. Shortly afterwards the Academy donated one of these faux Oscars to the History Department.

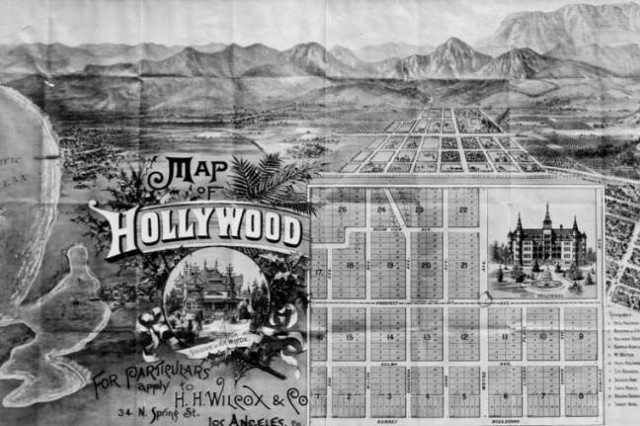

Where the Magic Happened

Perhaps the most unusual piece that Disney donated is the animation camera and stand that he used during his first years in Los Angeles. Visitors can see this solid piece of movie history in the museum’s Becoming Los Angeles exhibition. When Walt Disney built this animation stand in 1923 out of lumber from a shipping crate in his uncle’s Southern California garage, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences did not yet exist. The organization was founded in 1927, the year before Disney’s most famous character, Mickey Mouse, was first animated on its table. The animation stand remained in use until early 1930, creating the early Mickey Mouse cartoons as well as the first Silly Symphonies. The apparatus was designed for showing action by photographing drawings of the successive positions in a character's movements against a painting of the background.

When Disney gave the animation table to the museum in 1938, he told the staff that it had been used in several Mickey Mouse cartoons, including Plane Crazy (1928), inspired by Charles Lindbergh's flight from New York to Paris, and Steamboat Willie (1928), which was not only Mickey's debut, but also the first cartoon incorporating sound.

Oscars were only one type of honor awarded to Disney in the 1930s. Mickey Mouse was a cinematic superstar, recognized around the world. His cartoons were so popular that audiences from India to Sweden demanded theaters show seven or eight Mickey Mouse cartoons back-to-back, while in communist Russia his cartoons were deemed “of cosmic value”.

In Mickey’s hometown, NHM was the first museum to stage an exhibit of Disney’s animation art. The Seaver Center for Western History Research, which houses Theisen’s film frame collection, currently has a grant from the Louis B. Mayer Foundation to digitize the collection, providing access to researchers everywhere to study Disney’s production process, frame by frame.

As Disney once famously stated, “Let’s not forget that it all started with a mouse.”