BE ADVISED: The Natural History Museum is not participating in SoCal Museums Free-for-All on Sunday, February 22.

About two hours north of Los Angeles lies a treasure trove of natural beauty within the shelves of Red Rock Canyon State Park, not to be confused with (though comparable to) the majestic sites of a similar name in Colorado.

A well-trained movie buff’s eye might recognize the site’s peaks and valleys from such films as The Mummy (1932), Planet of the Apes (1968), or even Jurassic Park (1993), but this particular excursion was no sightseeing tour—it’s a museum tradition well over 100 years in the making.

For our humble museum crew—videographers Edgar Chamorro, Daniel Caballero, and myself—the prepping and packing up of the car began before daybreak. By 4:45 am, we were ready for the day’s adventure to our outer city destination, but not without breakfast and a tall coffee, of course.

Open to researchers, docents, and post-doctoral students alike, many a group have made the trip out to the familiar desert and its Ricardo Campsite, prospecting the land in hopes of not only learning about the history of its environment but the animals that once roamed its vast plains. At the helm of the research are NHMLAC Research and Collections Curators Xiaoming Wang, Dr. Emily Lindsey, and Dr. Regan Dunn, as well as University of Michigan experts Catherine Badgley, Fabian Hardy, and Lucas Weaver.

Diana Kou

A half-jacketed rhino pelvis found in the field.

Diana Kou

The team extracted a rhino pelvis, perfectly plastered with Xiaoming Wang’s field number and locality code.

1 of 1

A half-jacketed rhino pelvis found in the field.

Diana Kou

The team extracted a rhino pelvis, perfectly plastered with Xiaoming Wang’s field number and locality code.

Diana Kou

Following a desiccated trail, the path seems windy and errant. A mix of both shallow sand and dry patches riddled with pebbles, the occasional pause is taken for further examination of the land itself. From an upturn of rocks to the crumbling of dirt in the very palm of a hand, each granule tells its beholder what the lay of the land may have looked like hundreds of years ago. What climate did the environment endure? What animals may have roamed in these territories? What may have led to their demise, and when?

Diana Kou

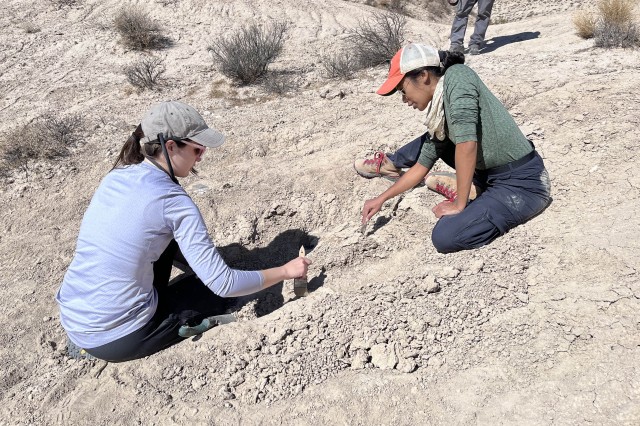

Juliet Hook and Dr. Mairin Balisi work on excavating a stubborn camel radius in the field.

Diana Kou

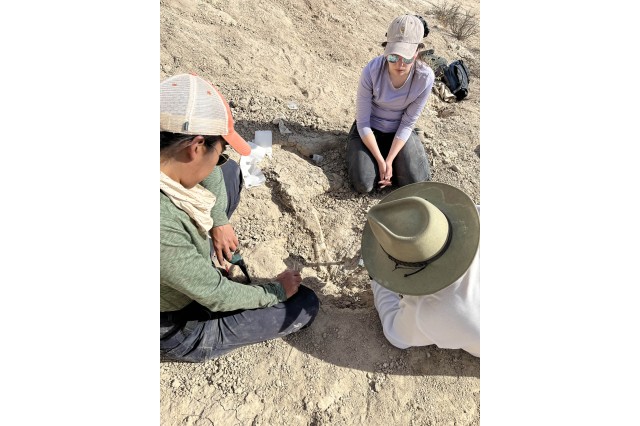

Dr. Mairin Balisi, Juliet Hook, and Xiaoming Wang take a closer look at the excavated bone.

1 of 1

Juliet Hook and Dr. Mairin Balisi work on excavating a stubborn camel radius in the field.

Diana Kou

Dr. Mairin Balisi, Juliet Hook, and Xiaoming Wang take a closer look at the excavated bone.

Diana Kou

It’s then Juliet Hook (Assistant Collections Manager, Vertebrate Paleontology) who shares that she has stumbled upon what appeared to be a bone protruding from the dirt, easily mistaken for petrified wood or mere trash to the untrained eye. Hook, joined by Dr. Mairin Balisi, decided to take a closer look.

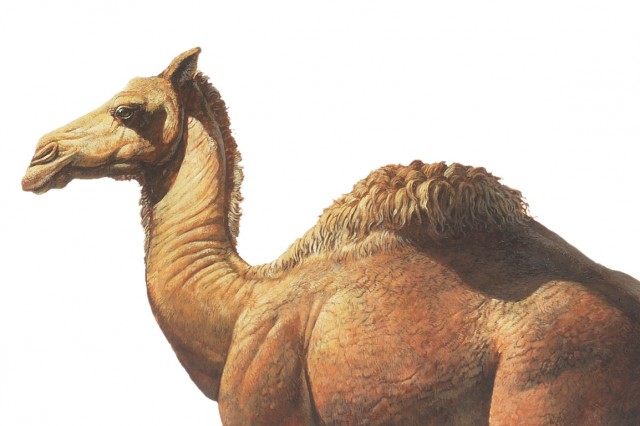

Although early assumptions pointed to Camelops (an extinct genus of camels that lived in North and Central America), further inspection suggested the fossil could also be an elephant proximal tibia or rib. In the end, gut instinct proved correct—the 9-million-year-old fossil was indeed the radius of a camel, likely buried within a year or two of its death. The find is a first for Hook in the field!

Diana Kou

Curator Xiaoming Wang in the field.

Diana Kou

Cassidy, companion of Dr. Regan Dunn, takes a breather beneath a cool shade in the field.

Diana Kou

The human caravan roams the desert.

Diana Kou

Senior Video Producer Edgar Chamorro captures the scene.

1 of 1

Curator Xiaoming Wang in the field.

Diana Kou

Cassidy, companion of Dr. Regan Dunn, takes a breather beneath a cool shade in the field.

Diana Kou

The human caravan roams the desert.

Diana Kou

Senior Video Producer Edgar Chamorro captures the scene.

Diana Kou

While present-day animal encounters may simply include roadrunners, mice, lizards, hawks, and squirrels, various species have roamed the 27,000-acre span that is Red Rock Canyon. On the routine trip alone, the La Brea Tar Pits preparator team came across a bone bed of horse and saber-toothed cat teeth in addition to the aforementioned fossil finds, with preparator Alan Zdinak working on a partial Smilodon skull retrieved earlier in the exploration process.

Regular research and prospecting are crucial to understanding the history that lies not only beneath the surface of this historical site formed three million years ago, but many like it, proving there is far more to any book (or a marvelous bed of rocks) than its cover may suggest. What will we find next in the field? Only time will tell.