It takes teams of artists, gemologists, and master craftsmen like Robert Procop a lifetime of study and practice to turn a natural gem into something like the Blue Splendor of Ceylon, but the Earth moves mountains to produce the uncut sapphire.

Courtesy of Robert Procop

Tectonic Plates

At the roots of some of Earth’s greatest mountains, molten magma slowly cools, only to be reshaped by the movement of tectonic plates. “The Himalayas is a classic example where two continents came together, Asia and India – India's still moving into Asia,” says NHM’s Dr. Aaron Celestian, Curator of Mineral Sciences. “And when those two continents collide, the high pressures and temperatures that are generated allow for some of these gem minerals to form.”

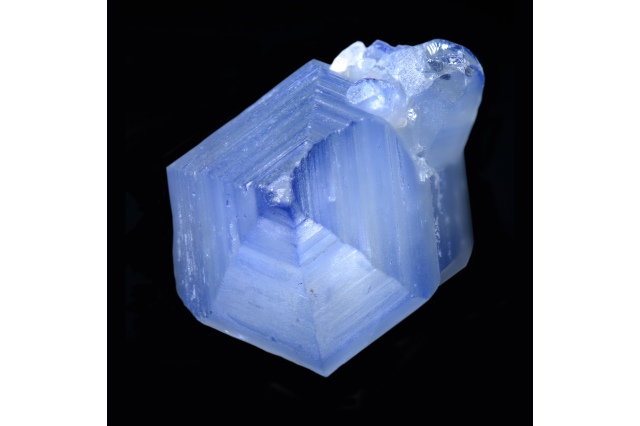

Sapphire is the gem form of the mineral corundum. Pictured here is corundum from NHM's Mineral Sciences collections of 150,000 specimens, including more than 140,000 minerals 3,000 rocks, 3,000 gems, and 50 meteorites.

Photograph by Stan Celestian

An overhead view of this corundum specimen highlights its 'growth rings'. In minerals like this one, they capture the titanic movements of tectonic plates over millions of years.

Photograph by Stan Celestian

There's much more to corundum and their gem form sapphires than just a pretty facet.

Photograph by Stan Celestian

1 of 1

Sapphire is the gem form of the mineral corundum. Pictured here is corundum from NHM's Mineral Sciences collections of 150,000 specimens, including more than 140,000 minerals 3,000 rocks, 3,000 gems, and 50 meteorites.

Photograph by Stan Celestian

An overhead view of this corundum specimen highlights its 'growth rings'. In minerals like this one, they capture the titanic movements of tectonic plates over millions of years.

Photograph by Stan Celestian

There's much more to corundum and their gem form sapphires than just a pretty facet.

Photograph by Stan Celestian

Taking place over tens of millions of years, the collision is at once mind-bogglingly slow, unimaginably violent and utterly transformative, producing temperatures hotter than 900˚C and more than 9,000 atmospheres of pressure. “Deep in the roots of those mountains in the Himalayas, you'll find sapphires starting to grow, and they're growing because the minerals that were there to begin with are no longer stable, so they slowly transform to minerals that are stable at these immense pressures and temperatures.”

The Isle of Gems

The Blue Splendor of Ceylon takes its name from one of the most important producers of sapphires. Known as Ceylon under British colonial rule, Sri Lanka has gone by a more poetic name in Sinhalese for a long time: Ratna-Dweepa which translates to Isle of Gem Stones. Recorded in literature as a source of sapphires as far back as the 2nd century, the origins of those deposits reach even further, into the prehistoric past, between 450 and 750 million years ago.

Photograph by Sarah Nichols used under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Tectonic plates carrying the eastern and western pieces of the ancient super-continent Gondwana collided for 300 million years in what is now called the Pan-African mountain building event, and the slow-moving, earth-shattering crunch left the Madagascar–Tanzania Gem Belt in its wake. One end of that belt is the sapphire deposits in Sri Lanka. The stones being mined today result from the collision of tectonic plates long before the age of dinosaurs.

Sapphire or Ruby? It’s a corundum.

The pre-Cambrian (a time period from 541 million to 4.5 billion years ago) plate pileup was just one of four main periods recognized by scientists where corundum formed. The second hardest mineral after diamond, corundum is better known by its two gem forms: sapphires and rubies. Rubies are red, and every other color is a sapphire. Trace elements of things like chromium, impurities in the crystal , provide the pallet of these corundum gems.

Photograph by Stan Celestian

While its distinct hue reflects the chemical makeup of the stone, the tens of millions of years of mountainous churn and tectonic collision are written inside the gem.

“If you look closely at it, you might see some bands of light-colored, dark color, light, dark, dark, light, dark, light, dark, and those are representative of the growth patterns of the mineral,” says Dr. Celestian. In much the same way a tree ring reveals years of drought or fire in the size of its rings, crystals recount their long lives underground. “If there's a period of time where there's fast crystal growth, then one of those bands is going to be big. Or if there's a period of time where there's lots of impurities around, then one of those bands is going to be darker in color. So they're recording all those events that are taking place all in that one crystal.” There’s millions of years of geologic happenings in one dazzling blue package.

If you can’t get enough sapphire, Brilliance: The Art and Science of Rare Jewels features corundum of all kinds, from the world’s largest pink sapphire to color-change and star sapphires among the hundred incredible pieces of jewelry on display. Explore Earth’s vast history through the facet of rare gems at NHM.

This exhibition was organized by the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County in collaboration with Rober Procop Exceptional Jewels.