There's a Feather for That

Bird Curator Allison Shultz lays out the surprising powers of plumage and how understanding feathers helps humans—and helps humans to help birds.

image by Allison Shultz

Published April 26, 2023

Despite being some of the most beautiful parts of any animal, feathers have a way of fading into the landscape of birds, which is a shame, because feathers are flocking incredible.

Feathers are nature’s own multitool. They put Swiss army knives to shame with everything they help birds do. There’s flying of course, and looking fly (to attract mates), and that’s barely scratching the surface.

“Unlike many traits that animals have, most bird species change their feathers at least once a year, sometimes multiple times a year,” says Dr. Allison Shultz, Assistant Curator of Ornithology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. “They need to do that to refresh them because they break down over time, but also that can enable them to change functions—just like we would download a new app on our phones." Feathers are birds' everything tool, and they’ve been refreshing them way before any of us couldn’t get to work without our smartphones.

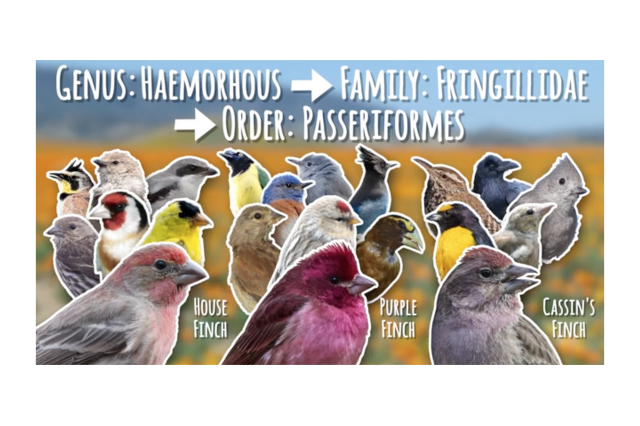

image by iNaturalist user Michael Bunsen

“I can't really think of any single trait that’s so all-encompassing in terms of the life of an animal as feathers are,” she says, and if anybody knows how all-encompassing feather functions are, it’s Shultz. Her recent paper in the journal Biological Reviews lays out an impressive display of 26 different feather functions, collecting everything scientists know about what birds are doing with feathers (so far!).

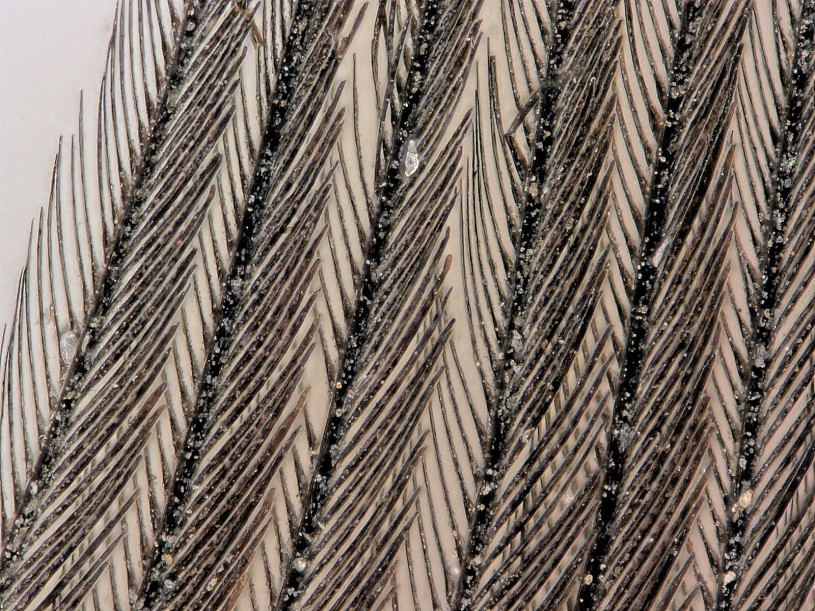

Shultz’s own research gets a closer look at feather structure to see exactly how feathers do everything they do. Using hi-tech tools like NHM’s scanning electron microscope, Shultz studies the sophisticated physical structures that make things like vivid colors of feathers possible (among other birdy topics).

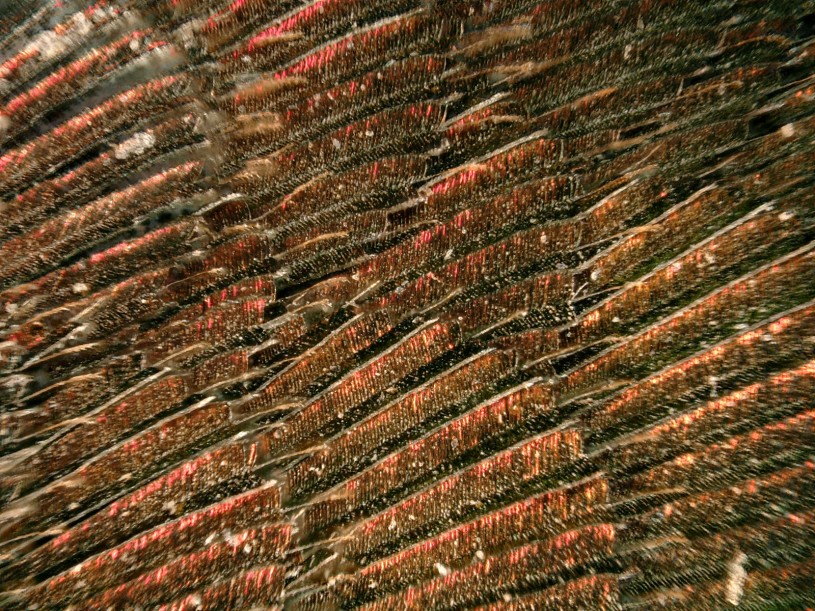

A feather’s microstructure lies beyond what we can see with the naked eye the barbs (think of a stem) and barbules (leaves on that stem but for feathers) above are the source of some birds' dazzling colors, like the male Ramphocelus flammigerus, or flame-rumped tanager pictured above magnified under a powerful microscope.

image by Allison Shultz

The intricate structures manifest themselves in the dazzling colors of the male flame-rumped tanager (Ramphocelus flammigerus) pictured above. Shultz's research uncovered that these structures were responsible for the incredible coloration as opposed to chemicals from their diet.

image by Allison Shultz

1 of 1

A feather’s microstructure lies beyond what we can see with the naked eye the barbs (think of a stem) and barbules (leaves on that stem but for feathers) above are the source of some birds' dazzling colors, like the male Ramphocelus flammigerus, or flame-rumped tanager pictured above magnified under a powerful microscope.

image by Allison Shultz

The intricate structures manifest themselves in the dazzling colors of the male flame-rumped tanager (Ramphocelus flammigerus) pictured above. Shultz's research uncovered that these structures were responsible for the incredible coloration as opposed to chemicals from their diet.

image by Allison Shultz

Some of her recent work uncovered how feathers’ microstructures help birds like tropical tanagers achieve their beautiful bright hues. Shultz found looking at feather functions more broadly—laying out everything they could do—changed how she thought about plumage, even with her feather expertise. For non-bird experts like you and me, it will change how you think of feathers and the birds that use them.

Sound and Vision

While they might be nature’s most famous singers, some birds are multi-instrumentalists—they use their feathers to manipulate and make sounds. Hummingbirds’ beautiful gorgets—the bright metallic feathers around their necks—are just one of the ways these little birds pump up the volume. Besides the humming sounds their blindingly fast-moving wings make, some male hummingbirds can make a high-pitched trill when divebombing to attract mates. The Allen’s hummingbird found all over coastal California for example, uses its middle tail feather to make the sound itself and the second-from-the-outside feather to really crank up the volume.

image by iNaturalist user Andy Kleinhesselink

Doves and pigeons are some of the birds that produce sound to startle would-be predators while they escape, and at least one bird uses its feathers to ‘sing’—like a cricket. The club-winged manakin rubs its feathers together to make a high-pitched call, vibrating its wings faster than hummingbirds.

Each of these sound production methods is made possible by feathers with modified shapes, sometimes greatly changed and other times so slightly different that they might be hard to notice. Scientists think that most feathers used for flying can make some sounds, so more birds might be working on their demos as you’re reading this, even while some birds are using their feathers to hear.

Nocturnal owls do their hunting at night without the benefit of a bird’s eye view, relying instead on finely attuned hearing. Barn owls have turned feathers into a heavy-duty listening device, using a facial disc of feathers to amplify the sounds of prey and pinpoint their location in complete darkness. These concave feather structures funnel sound directly to the owl’s inner ear while velvety feathers on the wing smother the swooshing sound of the bird’s dive bomb.

Feathers are more famous for their flashy colors than sound manipulation, but feathers can go even further than colors (and colors go a lot deeper than you might think). Here are just some of the under-appreciated ways birds make themselves seen with feathers.

image by iNaturalist user Claudia Schipp

Birds molt throughout the year, losing and gaining brighter feathers to attract mates or make stronger feathers to support long migrations. But some birds get real fancy. They have specialized down feathers that they crush with their bills and then apply to their feathers. Think of it like rouge or highlighter, concentrated color to help a bird stand out among the flock. Some of the birds using this feather-made self-care routine are cockatoos and parrots, but herons are the best-known examples of birds that like to get their feathers done.

While many young birds use feathers to blend in with their surroundings (a strategy of camouflage called crypsis) some chicks take it way in the other direction. Juvenile cotinga from South and Central America use their plumage to produce bright colors and patterns, becoming more visible, but visibly resembling toxic caterpillars (a cross-species copying called Batesian or Mullerian mimicry) Nestlings appear to also move like the caterpillars to really sell the ‘I’m a poisonous larval butterfly and not a delicious, helpless, baby bird’ act.

Other birds use feathers for more than looking poisonous. Birds in the genus Pitohui from New Guinea actually have toxic feathers, a surprisingly recent discovery—and the first known instance of a bird having a toxic chemical defense, a well-known tool in reptiles like cobras; amphibians like poison dart frogs; and mammals like duck-billed platypuses. Pitohui’s feathers contain a neurotoxin—the same kind found in poison dart frogs. Touching their feathers can lead to numbness and tingling, and burning. Exactly what these birds are doing with their poison feathers is still being studied. Are they deterring predators or parasites? Females impart the poison onto their eggs, and researchers have recorded snakes vomiting up those eggs, so it could be used to protect their young, or maybe it’s for all of the above. They’re at least deterring the locals who only eat what they’ve dubbed the "rubbish bird” as a last resort.

Feathers For All Functions

Birds in the sandgrouse family use their earth-toned plumage to hide in their dry environments, but those camouflaging feathers are hiding a secret all their own. Grousing through the sand is thirsty work, and these birds typically nest far from water sources. To keep their thirsty chicks hydrated, male sandgrouse bring water back to the nest—with their feathers.

image by iNaturalist user Jan Ebr CC BY-NC

If you’re picturing a bird holding water in its wings, stop right there. Sandgrouse water-carrying feathers work through the structure of their barbules—the filaments extending from the larger barbs that branch out from the central shaft—structures way too small to see without a microscope. The coiled barbules unfurl when wet to collect water through capillary action—the same action that lets butterflies collect liquid with their mouthparts. The male sandgrouse will then carry its precious fluids back to the nest for its thirsty offspring. Water carrying is rare enough in the animal kingdom, but the tool for carrying water in these birds is the same tool other birds use for waterproofing, staying afloat, and swimming, highlighting the fluidity of function only feathers can achieve. Hundreds of millions of years of adaptation have produced feathers capable of darn near everything while human ingenuity is still catching up.

Feathered Mammals

If you’re reading this, it’s almost certain that you’ve already integrated feathers into your life for similar reasons as the animals that produced them. Flashier feathers that might attract mates among birds are used in our clothing and costumes to draw attention to us. Feather functions like insulation used in lining nests and just plain insulation have already made their way into human technology. The highest-quality puffer jackets and duvets are still stuffed with down, a feather-like structure found in birds like geese that have yet to be matched by human ingenuity.

“We need to study what nature is doing and how it's doing it—that can really advance discoveries in the human world.”

Dr. Allison Shultz

“The biomimicry possibilities of feathers to benefit humans and technologies is pretty immense,” says Shultz. Bird scientists like Shultz uncovered the intricate nanostructures that help leafbirds create their eye-popping hues could help all sorts of light-conducting technologies—everything from fiber optics to solar cells—be more efficient. “People are trying out new ways of printing things based on how birds put their pigments down. The way that structural color forms in the feathers is being used to influence how fiber optic cables get created because bird nanostructure within their feathers is self-assembling.” Birds don’t need advanced mechanical productions to create advanced light conduction technology. “It just does it on its own. We need to study what nature is doing and how it's doing it—that can really advance discoveries in the human world."

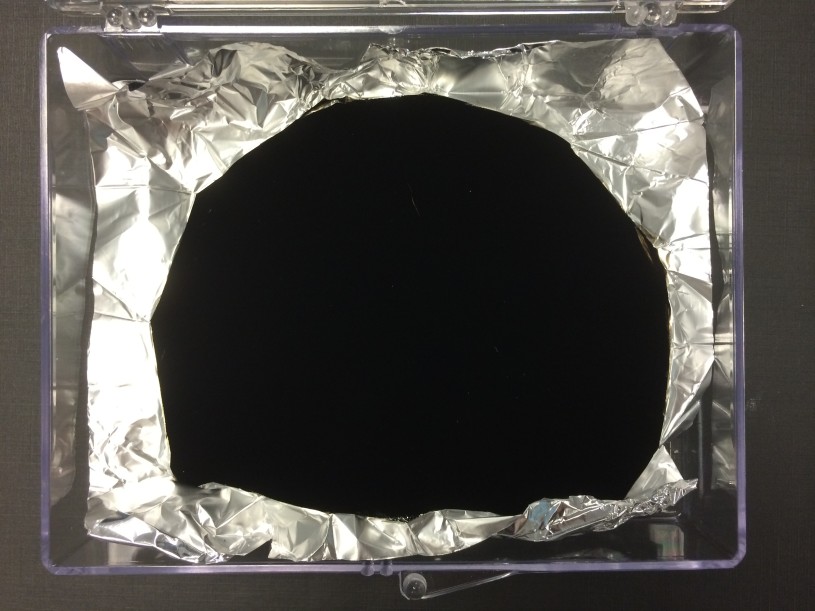

image by Surrey NanoSystems CC BY-SA 3.0

Shultz’s own research has helped unlock the secret of how birds have achieved mind-bending dark super black, a hue we’ve only been able to produce since 2014. “There are examples where humans have come up with something—things like Vantablack paint—that uses the same kind of concepts, but birds had already done that millions of years ago,” says Shultz. Advanced microscopy and other analysis tools will only add to the growing list of how feathers can help humans.

image by Allison Shultz

Ducks and Covers

While we isolate the functions we find most useful to us, birds are constantly using their feathers to do it all. So arranging all of these functions together is more than just an impressive display.

“So many of us scientists focus on one aspect at a time,” says Shultz. “Whether that be what color the birds are and how feathers are producing that color or how feathers are enabling birds to fly. But the fact that feathers are doing all of these things simultaneously has really demonstrated to me the importance of considering all of the different things that feathers do and how they might be influencing each other.”

image by iNaturalist user gtguy CC BY-NC

Consider the mallard. Better yet, head out to your closest park with a pond and take a gander at one yourself. These ducks are so common, it’s easy to forget how vivid and rich their feather coloring is. You’ve probably noticed the male’s distinct shiny green heads or maybe even the iridescent blue color popping from their wings. These glamorous feathers conflict somewhat with life in the pond. “Why wouldn't ducks necessarily be that colorful all over their body?”

“The structure that creates iridescent color actually makes a feather less waterproof, “says Shultz. “If there were selection for a trait to make a bird be more iridescent, that's actually at odds with them being able to be waterproof. You might change one trait to be a certain way, but actually, selection might be acting in another direction. Those different functions that might be at odds with each other.”

None of a feather’s functions happen in a vacuum and pushing towards say flashier feathers might make it harder to keep dry, but they could have even more interactions we’re still learning about. “A recent study found that actually iridescent color also absorbs more heat than other sorts of coloration mechanisms and because of what's called the melanin pigments, which are pigments that tend to absorb a lot of light that's important in iridescent colors.”

Iridescent color also interacts with functions like regulating heat—keeping warm or cool enough to survive the climate, so that’s at least three different impacts shiny feathers have on mallards. Recognizing the balancing act birds are doing with feathers helps Shultz and other bird researchers think about the push and pull of different feather functions, informing their understanding of how well birds might be able to adapt—or not—to our changing climate and other environmental disturbances like urbanization and habitat destruction.

image by iNaturalist user Andy Wilson

Shultz and other bird researchers will continue to unlock new discoveries about feathers, helping humans achieve things birds have been doing for millions of years and how we can make sure they’re still around to inspire and amaze us into the future. So be on the lookout for new feather finds, and the next time you see your favorite bird, ponder the power of its plumage.