BE ADVISED: On Saturday, February 21, the Natural History Museum will be closing at 4 pm. The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum will host the LAFC vs. Inter Miami soccer match, with kickoff at 6:30 pm. This event will impact traffic, parking, and wayfinding in the area due to street closures. Please consider using public transportation or rideshare.

BE ADVISED: The Natural History Museum is not participating in SoCal Museums Free-for-All on Sunday, February 22.

Wonder Girls

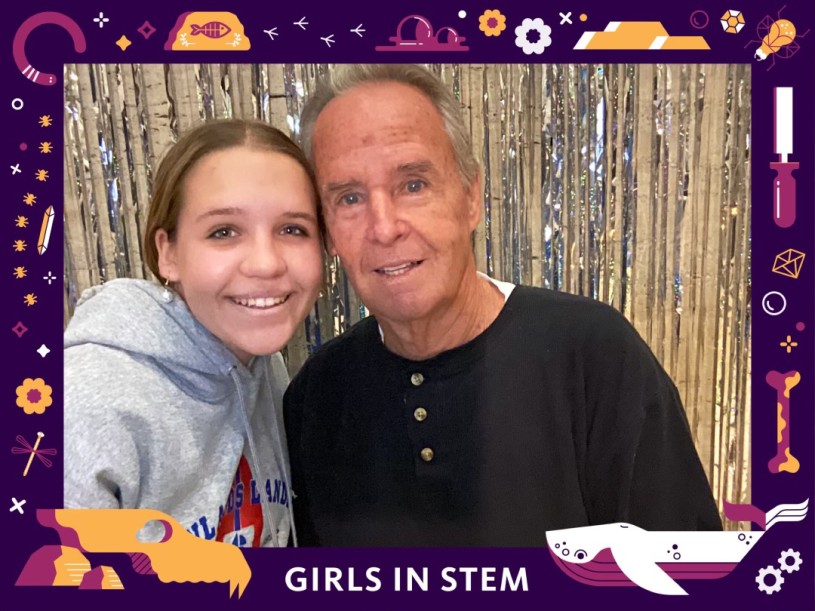

A contingent of 8 to 18-year-olds spent three inspirational days at NHM learning from experts about fossils, mammals, and oceans, and discovering the many stepping stones to careers in science, technology, engineering and math.

Published May 5, 2023

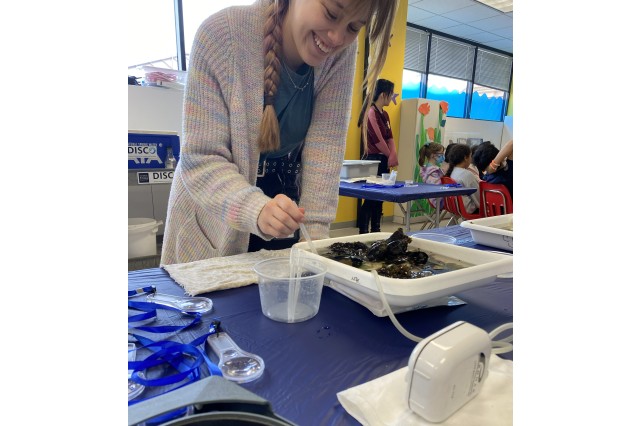

Hundreds of 8-18-year-old girls spilled into the Natural History Museum over the last few months for a series of all-day science-infused inspirational gatherings created just for them. At these Girls in STEM Days held in February, March, and April, participants picked a bat alter-ego, dipped their fingers into slimy aquaria, and learned how to excavate fossils. There was so much joyful juvenile discovery, artistic intention, and mind-enhancing problem solving in the halls and galleries that the cerebral synapse-firing was palpable.

During these STEM (Science Technology Engineering and Math) workshops and activities, the girls, broken up into the younger (8-12-year-old) and older (13- 18-year-old) cohorts worked elbow to elbow alongside NHM women scientists and museum educators, exploring one fascinating topic each month. February was Oceans. Fossils ruled March. Mammals governed April. Here’s a recap of those three electric days through the eyes of museum scientists and educators and their fellow, and future, voyagers, excavators, and urban nature explorers.

1 of 1

The Shallows and the Deep

During the oceans-themed February day, girls joined hands-on workshops with the scientists from the NHM’s Marine Biodiversity Center (MBC). They saw and touched real marine specimens from local coastal California environments, and learned how steadfast methodical research is illuminating more about the diversity of aquarian denizens just offshore. Becca Prater, a Museum Educator and Certified Interpretive Guide set up the tide-pooling experience for the kids to observe marine life up close.

“A lot of them wanted to spend the entire time looking through the kelp to find more critters. We focused on sparking that curiosity and showing them new animals they had never seen before.” Prater’s favorite part of the day was recreating the "dance moves" of polychaetes (segmented worms) that shimmy and wiggle in their deep sea habitats. There was also an art station where the kids could color or draw animals and add them to a large collaborative mural depicting life in the sea.

“They really loved seeing photos from the MBC's work out in the field and making the connection that the people working with them also spend time scuba diving and collecting specimens for study.”

Caroline Haymaker, Associate Collection Manager with the MBC, also said it was a joy to participate in the day.

"I was eager to see if I could inspire any participants the way the ocean's creatures inspire me," she said. "It's hard not to be amazed by the tiny organisms that make their way out of clumps of kelp, mussels, and barnacles. It was a delight to see their reactions to these live invertebrates, that they otherwise may not have the chance to see."

Leslie Harris, NHM’s Polychaetes Collections Manager, talked with the girls about the behavior, habitat, and life history of the specimens on display. Some of the family members also asked about climate change, pollution, and invasive species.

“Talking to kids and their families is great fun and I always hope for a couple of "sparks"—kids and teenagers who are sincerely interested in science of any type, and involved adults who follow their kids.”

Diana Sanchez, Program Manager, School and Teacher Programs at the La Brea Tar Pits remembers how deeply engaged the girls were in the invertebrate sorting activity, which involved meticulously separating out the spineless wonders. Sanchez recalls one particular girl, perhaps a junior or senior in high school, who volunteered that she was drawn to studying heavy metals and their effect on ocean life.

“We encouraged her on her path and reiterated the importance of studying biodiversity to try to best understand the relationships plant and animal species have with their environment; especially as many scientists are looking at marine animals as our next major food source for a growing human population.” Eight-year-old Sabrina Romo, a third grader from Glen Oak Elementary in Covina, who attended all three STEM days, graded the oceans day as well above average.

“The undersea experience was really good,” Sabrina said. “You had two choices. You could either color or suck up the animal with an eyedropper from a jar. There were snails in there and tiny starfish but the water itself had animals in it and you can see them using a magnifying glass…Some were camouflaged to protect themselves from predators, so they could swim by them without noticing.”

A participant in Girls in STEM Fossil day inspects a real Allosaurus femur

Participants learned field techniques, how to sort fossils and prepare them for study

1 of 1

A participant in Girls in STEM Fossil day inspects a real Allosaurus femur

Participants learned field techniques, how to sort fossils and prepare them for study

Fossil Dig Indoors

In March, another crew of girls showed up at NHM’s door to dig into paleontology. NHM's Dinosaur Institute’s experienced fossils hunters were their guides for the day. In hands-on workshops, they plumbed for answers about ancient life, working with real fossils and tools alongside scientists with immense knowledge about our planet's prehistoric past. In the bustling “STEMinist Lounge” the kids examined specimens brought out from collections rooms behind the scenes.

They learned about career opportunities from representatives from the Western Science Center, California Geological Society, Southern California Paleontological Society. Erika Durazo, Senior Paleontological Preparator in the Dinosaur Institute, who has personally unearthed untold numbers of bones in dusty quarries over the years, was thrilled to share her field experiences and expertise with the crew of curious potential fossil hunters.

“We bought a large pack of random fossils, including mosasaur teeth and snake vertebrae. We set them in plaster, gave them dig kits (dental pics and brushes) and taught them how they could use different tools and techniques and apply different pressures” to separate the surrounding dirt from the bones cradled in a plaster jacket. “I told them 'these are millions of years old so no rush!’ ” Still, some of them were aggressively excavating so the bones crumbled. When that happened, the lowkey Durazo recognized the teaching moment. “I showed them that things do break, and how to fix it. I would have a little kit and be the fossil nurse, and put it back together piece by piece.” If they didn’t finish prepping the bones, they could bring the fossils home, along with their hand-drawn quarry maps and a newly acquired skill set.

“Dinosaurs were not in my radar when I was a kid. Personally I like to be part of things like this because any bit of exposure is so important. Even if they don’t go to paleontology, it’s great for them to just know that there’s another option for a career path that they didn’t know existed.”

Erika Durazo, Senior Paleontological Preparator in the Dinosaur Institute

In-the-Field Trainees

These quarry stories were valuable nuggets of knowledge to 13-year-old attendee Piper Agee.

“They talked about how sometimes they would go out and they would find small pieces of bone, and how it would suddenly complete a fossil,” said the 7th grader who goes to Tuffree Middle School. It could help to indicate certain previously undescribed functions, she said.

“It would tell them how the dinosaurs would live or where they lived even. I just find it really interesting that we have the ability to restore the bones of animals that lived so long ago.”

Learning about the stepping stones to a career in paleontology was another nifty pickup. “She told us about how she worked in the field and took some pictures out on trips when she'd go and dig for these bones. I thought it was really cool to listen to how she got there, and how she went to college and got her degree and now does what she loves to do.”

Mammals Are Us

Trina Roberts, Associate Vice President for Collections, spent the April Girls in STEM day with the younger group of 8-to 12-year-olds eager to know all about their warm-blooded neighbors.

“We chose a selection of skulls, pelts, and a few other kinds of objects from the mammal collection and the educators' collection and asked the participants to look at the skulls on their tables, and see if they could infer from the teeth and the size and shape of other parts of the skull how that mammal made its living.”

There was a lot of good observation and inference about sharp biting teeth vs flat or ridged grinding teeth, front teeth vs molars, and a lot of interest in some toothless mammals. They considered the kinds of food mammals might eat and why some skulls might look so different from others. They also considered the what and whys of fur—skunks with warning coloration, both predators and prey decked in camouflage, aquatic otters with dense fur. Participants were encouraged to take notes or sketch their observations. They also were invited to "build a mammal" on a sketching worksheet, imagining where and how their dream mammal lived and what physical characteristics it possessed. What was its shape and size and color/pattern? Did it have teeth, antlers or horns, feet or claws?

“The results of that were wonderfully thoughtful and creative, and gave them something to take with them to show their grown-ups,” Roberts said. “Of course we also asked them what their favorite animal was, and had solid representation from mammals as well as a smattering of other things (dinosaur, crocodile, snake, birds...). Roberts also showed the group photos of the mammalogy collection, specimens that museum scientists use and also loan to other people who want to do science, just like the participants can borrow books about their favorite animals from a library.

“I was interested in being part of the day because a lot of kids know a ton about animals from TV shows and books, but might not have ever had a chance to get up close to a platypus or a lion's skull. I wanted them to see that doing science includes skills that they already use all the time, is fun, and is done by people who are like them and enjoy asking questions about how the world works.”

Bat Girls

Shannen L. Robson, NHM’s Mammalogy Collections Manager, was with the 13- to 18-year-old group on Mammals day and took them on a mini-tour of the collection. Then the group worked together in the prep lab measuring bat specimens and identifying the furry neighbors based on some visible characteristics.

“I was interested in participating because there aren't typically direct pathways into museum science and most students don't realize this is a professional track until well into college. I think it's important for students to be aware that museums employ scientists and share that experience with them.” Learning about bats was Piper’s favorite part of the day. “We looked at bats and how some had different types of ears for echolocation—how some bats had huge ears that faced forward and some had smaller ears that didn't stick out as much.” They measured forearm length, wingspan, total length of the bat, tail length—all information that can signal habitat and behaviors. With Robson as guide, the teens chose from a "which bat are you" list and made a button to wear home with a picture of the bat that matched their interests and personality.

Mexican free-tailed bats, for example, are social (they roost in large colonies). Western Red-tailed bats “love to wear interesting styles and bright colors” (their orange fur acts as camouflage in autumn leaves.) California Myotis are “tree-huggers” (they prefer forested areas and roost in the barks of dead trees.) “If you felt like that was true to your personality, you could make a badge,” said Piper. “That way we could find out more about what each girl was like.” At the end of the final Girls in STEM Day, the organizers felt confident that they’d achieved their main goal—to foster the “I see myself as a science person” identity. For many of these girls, the day they spent at NHM was a springboard to a pursuit they’d never before dreamed of.

“Personally, I’d like to be part of things like this because any bit of exposure is so important,” said Durazo, the paleontologist-adventurer. “This lets them know there are other career paths, and it’s worth asking people what they do because it can take you anywhere.”