BE ADVISED: Monday, February 16, the north entrance on Exposition Blvd will be closed. Visitors may access the Natural History Museum via NHM Commons or the south entrance, facing the L.A. Memorial Coliseum.

Off to Anacapa!

Our Anthropology Curator heads to the Channel Islands on an unprecedented underwater archaeology expedition to find evidence of the first people to set foot on these shores

Published February 1, 2022

Under a sky stacked high with fog, NHM’s Associate Curator of Anthropology, Dr. Amy Gusick, and her fellow scientists embark on an unprecedented research cruise from the Santa Barbara Harbor towards the Northern Channel Islands. These aquatic cartographers are exploring a submerged portion of the coastline and scouting for ancient landscapes to construct a detailed undersea map of the past. Indigenous peoples arrived on those verdant islands at the end of the last ice age. But since they landed 13,000 years ago, the sea level has risen 300 feet—about the height of the Statue of Liberty—rendering three-quarters of the Northern Channel Islands underwater.

“What blows my mind is the fact that in Southern California and in the Los Angeles area, there has been habitation for over 13,000 years and probably longer,” said Gusick. “Right now the Northern Channel Islands are four separate islands, but when people first arrived there, they were all connected, forming one big super island called Santarosae. I think that's pretty amazing. We want to find some of these habitation sites that the initial settlers created, but, at this point, we do not know enough about the submerged landscape to locate these sites.”

What they hope will emerge from these sails—six so far—will be key to how this plunging coastline set humans on the move during the Pleistocene and early Holocene. Knowing how humans adapted then to sea level rise and climatic changes could provide insight into the population shifts and human migration being triggered today by global warming. Those shifts, with people on sunken islands heading to more hospitable terrain, will undoubtedly continue in the current geological period, the Anthropocene.

Channel Surfing

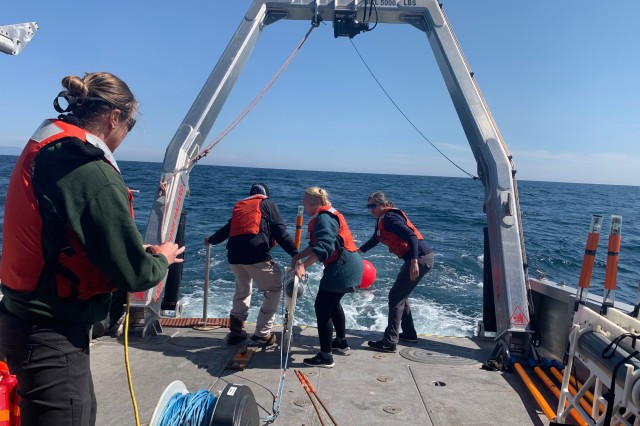

Keeping steady in rocky waters, Dr. Amy Gusick, left, and her colleagues deploy imaging equipment built to detect underwater tar seeps and evidence of ancient shorelines.

Since humans arrived there about 13,000 years ago, the sea level has risen 300 feet, rendering three-quarters of the Channel Islands underwater.

A undersea gusher. The team has already identified tar seeps, bubbling oil that oozes up from the fissures in the seafloor.

1 of 1

Keeping steady in rocky waters, Dr. Amy Gusick, left, and her colleagues deploy imaging equipment built to detect underwater tar seeps and evidence of ancient shorelines.

Since humans arrived there about 13,000 years ago, the sea level has risen 300 feet, rendering three-quarters of the Channel Islands underwater.

A undersea gusher. The team has already identified tar seeps, bubbling oil that oozes up from the fissures in the seafloor.

Motoring out on a 42-foot research catamaran that is pounding the four-foot swells like a rambunctious bronco, the sailor-scientists bring to mind the fictional ocean explorers scanning for the mythical lost civilization of Atlantis. The brave seafaring team includes marine geologists, geophysicists, biologists, and tribal knowledge holders. Dr. Gusick, an archaeologist, is joined by Dr. Jillian Maloney, Associate Professor of Marine Geology at UC San Diego, Roslynn King, PhD Candidate at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and Andrew Mendoza, a project intern and representative from the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. This nautical enterprise received funding from the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration.

By mid-morning, the fog has lifted, and as the sun-soaked vessel approaches Anacapa’s deep green hills, the captain stops the engine and deployment begins. As a team, Gusick, King, Gustafson, and Mendoza carefully release a bright blue cable out into the choppy water. It supports red plastic buoys spaced a few feet apart, warning Saturday sailors to avoid that particular patch of sea where the crew has planted their scientific-research-in-action flags.

They are deploying two imaging instruments that will help them to paint their geological treasure map. One, an acoustical monitoring device, will send sound waves bouncing beneath the surf. With every ping, it records data about elevation and sediment porosity, sketching the contours of an ancient landscape shrouded over centuries in thick layers of marine sand.

A few years ago, Gusick and colleagues from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography developed a special electromagnetic instrument that affords them another way to visually explore. The technology, nicknamed “CUESI”, sends back images as deep as 40 meters (or about 2,000 feet) below the seafloor. It can detect porosity, gaps, or patterns in the earth that could indicate the existence of ancient channels, rivers, estuaries, cliffs, and shorelines—the earliest SoCal beachfront property. It can even detect hydrocarbon (aka tar seeps), and distinguish between ordinary rocks and the shells that once glistened on the island’s rocky shoals.

Pinging the Deep

The team has already identified tar seeps, bubbling oil that oozes up from the fissures in the seafloor, a phenomena likely due to earthquakes triggered by a shifting Santa Rosa Island Fault. Tar was an essential tool for the tribal communities who lived on the islands. It served as a waterproofing agent for cooking vessels, water bottles, and boats and was used as an adhesive to affix a spear point or arrowhead to a shaft, among other uses. “Fishing was a very important aspect to the daily life of people that lived on the Northern Channel Islands and we've found fishing implements that still have tar on them, such as shell fishhooks, and even seagrass cordage with tar that may have been used to attach a hook to the line,” said Gusick. “Anything that you use tape or glue for now, or anything that you waterproof, the islanders would have used tar for that same purpose.”

That ultra-sticky substance also likely contains an ecological goldmine: microfossils. The infinitesimal bits of fossilized insects and preserved pollen can tell our paleoecologists what was buzzing and growing in the ancient environment, helping us understand what type of resources islanders had for daily living. In a follow-up island cruise this spring, the scientists will use an ROV to image and sample tar and minerals to bring back to the lab for study at NHM and La Brea Tar Pits.

Ancient Beachfront Property

The tribal communities in Southern California today have ancestors that lived on the islands; the Northern Channel Islands are the ancestral territory of the Chumash. In any projects the Museum embarks on, whether underwater, on the mainland, or the islands themselves, Gusick works with the tribes and tribal individuals. “I'm an archaeologist and I can understand specific things about archaeological sites and where they may be located across the landscape. Along with this type of information is another important type of knowledge needed to understand these sites, tribal knowledge. And that's something that I don't possess.”

On this latest sail, three Native American participants were part of the journey and two came on board the ships. They shared native histories, including information about seafaring and resource gathering that have been passed down from generation to generation to generation. “We're discovering multiple lines of evidence, multiple ways of knowing, and that makes projects stronger.”

One of the crew members on this particular sail was Andrew Mendoza, Project Intern from the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. On the ship, as the electromagnetic instruments were busy scanning the sea floor below, he said he was excited at the prospect of finding chert quarries. The hard, fine-grained super-sharp rock was used by Chumash people for the construction of stone tools and was heavily traded.

“No one has ever mapped this ocean floor. These are all big things for us because it’s telling us about our past, about who we are connected to. We know we were very social people and were able to learn from fishermen or hunters in different tribes,” said Mendoza. “It’ll be interesting to hear a little more about what we were doing back then. There are a lot of missing links to the story so this kind of fills it in.”

Watch this video to hear more from Gusick about this expedition and what's in store for the crew's next undersea adventure in 2023!