Bats in the Classroom

NHM Scientist, Miguel Ordeñana, finds bats and introduces them to classrooms in South L.A.

Bats are mysterious and often misunderstood creatures due to their nocturnal behavior and controversial reputation. This reputation is especially prevalent in South L.A., which includes some of the most park poor and industrial neighborhoods in L.A. These are the last neighborhoods most people, including even some scientists, expect to find wildlife. This reputation lowers the nature-viewing expectations of residents who have lived in these communities, in many cases, for many generations.

One of the primary goals of the Backyard Bats Survey, is to use community science to prove that even some of the most elusive species of the natural world exist everywhere, including within the most concrete-filled regions of L.A. In order to be successful, the project needed all hands on deck as Natural History Museum scientists and educators entered uncharted territory.

Now in its third year, the Backyard Bat Survey is significantly scaling up its sampling effort as it focuses on southern Los Angeles. Thanks to a generous grant from the Disney Conservation Fund, the study went from having 4 bat detectors to now having 20. We needed to install around 20 bat detectors at private residences that cover neighborhoods with varying amounts of tree canopy cover with wide geographic distribution in order to sample bats within a diversity of habitat types that exist within L.A.

We chose a subset of participants who were already involved in the SuperProject and BioSCAN, two projects that were sampling their backyards and neighborhoods for wildlife. Certain regions such as Culver City had received many volunteers for the SuperProject, but neighborhoods like Compton and Watts fielded far fewer potential candidates. That differential stems from a lack of awareness of our urban biodiversity research. Unfortunately, all of the funding in the world can’t buy you relationships that have been historically neglected for many years.

Our study had already incorporated public parks within these underrepresented neighborhoods, but we suspected that this sampling might not be representative of what we might find in residential areas. After a few families in Watts and South Central L.A. declined to participate, we decided to reach out to schools. The involvement of schools added much needed data points, and also gave us the opportunity to introduce our museum as a resource to faculty, students, and local families -- many for the very first time.

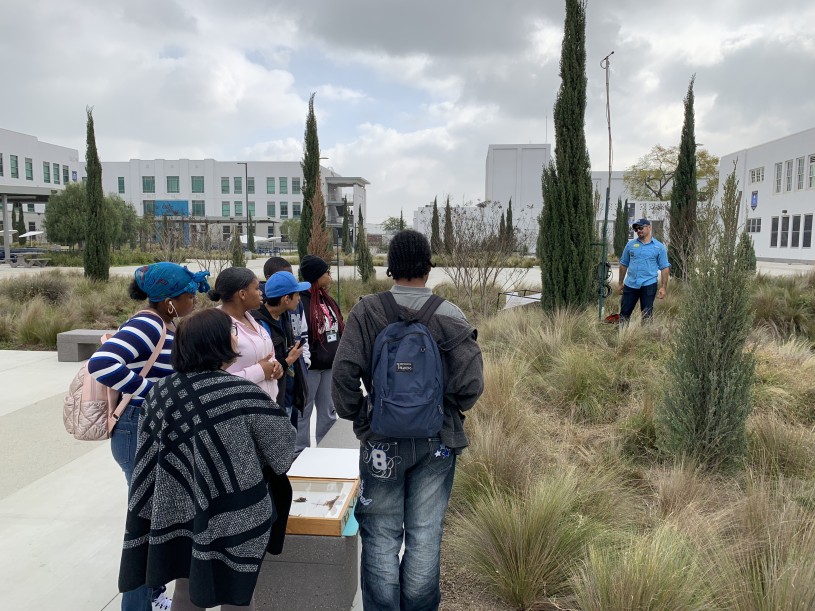

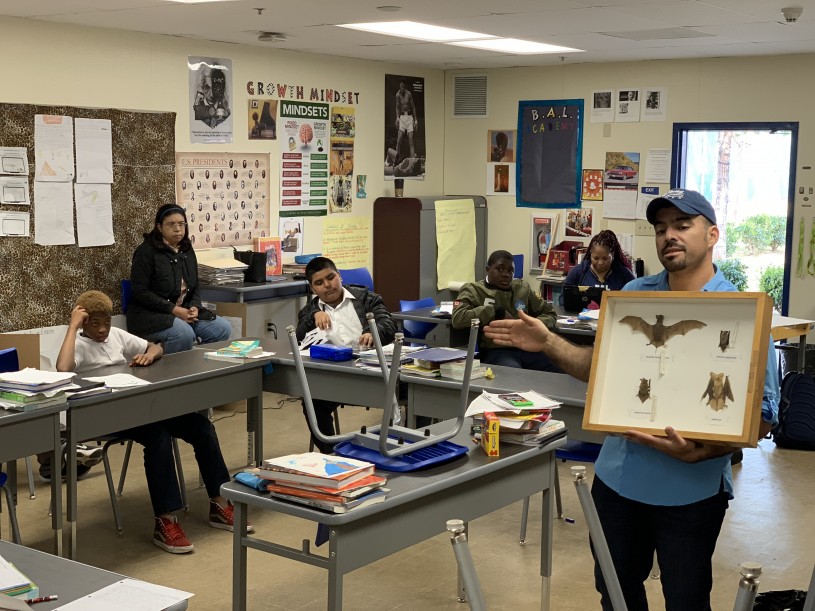

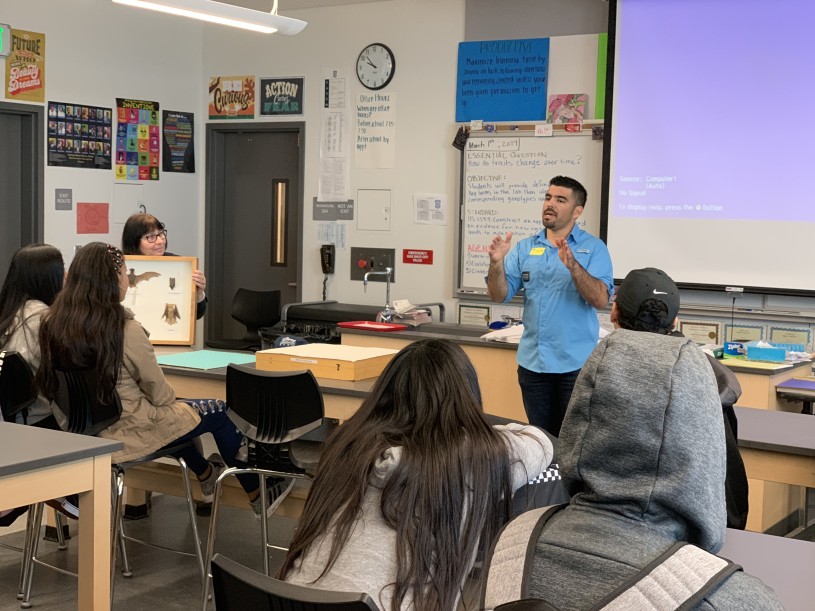

We ended up recruiting Jordan High School, Boy’s Academic Leadership Academy (BALA), and Animó Jackie Robinson Charter School. The teachers who were our contacts at each school enthusiastically volunteered their campuses to bat detection. It was great to now have data from these neighborhoods to compare to nearby parks, which capture the maximum number of bat detections for the area since they are oases for bats. Our school interactions began with the simple installation of a bat detector, but we are happy to report that these partnerships have grown into opportunities to share our work with multiple classes, including class visits and career talks. Our ability to inform the students of not just what species were found nearby but which bats were actually flying over their campuses, adds an impactful personal touch for these students. Additionally, our unique ability to show real museum specimens from our collections makes our discoveries more tangible and significantly increases the wow factor.

Our teacher contact at Jordan High School, Yolanda Grisolia, sent us a thoughtful message following one of Miguel’s career and local bat talks to a class. Her kind words suggest that our outreach and engagement are headed in the right direction toward building lasting relationships:

“Thank you so much. It was very helpful. You are helping to accomplish a worthy goal of exposing our underserved youth to things they would never know about otherwise.” - Yolanda Grisolia

Our next steps are to integrate this relevant local data into curricula so the impact of this survey is sustained long after the detector is moved to a different school or backyard. The success of our interactions with schools demonstrated so much potential that the Natural History Museum’s School Programs funded an additional bat detector that will be dedicated to sampling at schools. We also received invitations to record bats at high school football games, after one school’s students enthusiastically shared stories of watching bats hunt moths that were attracted to the stadium lights during a game. Does that seem familiar? Although some of these outcomes were unplanned, they were inspiring and hopefully mark the beginning of genuine long-lasting relationships between the Natural History Museum and local families who deserve a stronger connection with their Museum and wild neighbors.