BE ADVISED: On Saturday, February 21, the Natural History Museum will be closing at 4 pm. The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum will host the LAFC vs. Inter Miami soccer match, with kickoff at 6:30 pm. This event will impact traffic, parking, and wayfinding in the area due to street closures. Please consider using public transportation or rideshare.

BE ADVISED: The Natural History Museum is not participating in SoCal Museums Free-for-All on Sunday, February 22.

Digitized Mammals

How the new digitization project Ranges is unlocking the potential of NHM's Mammalogy Collection

Updated September 10, 2025

NHM’s vast collections are nothing less than a library of life on Earth, but when it comes to our Mammalogy Collection, much of the finer details of those specimens remain offline.

Through digitization, the National Science Foundation-funded program Ranges is bringing the traits of Mammalogy specimens online to become tools for transformative conservation science in areas like the biodiversity crisis and climate change.

Outlined in a new paper published online in the Journal of Mammalogy, the Ranges Digitization Network (Ranges) will bring even more detail to digitized mammal collections in western North America, including biodiversity hot spots like Los Angeles, where mammals are notably diverse and particularly threatened by human-caused climate change.

“By connecting the granular information of mammal specimens from 23 institutions, museum collections like NHM’s can become even more crucial to combating biodiversity loss by informing policy and research with a more detailed picture than ever before of how mammals are responding to things like habitat loss and the climate crisis,” says co-author, Dr. Kayce Bell. “We can more easily tell, for example, if a bat species' reproductive patterns have changed, and then policy makers and the public can better know what management strategies might help the species in a changing landscape.” Fellow co-author and Mammalogy Collections Manager Dr. Shannen Robson adds, "These digitized traits are a tremendous resource that has already been accessed to better understand biodiversity in places like the Channel Islands."

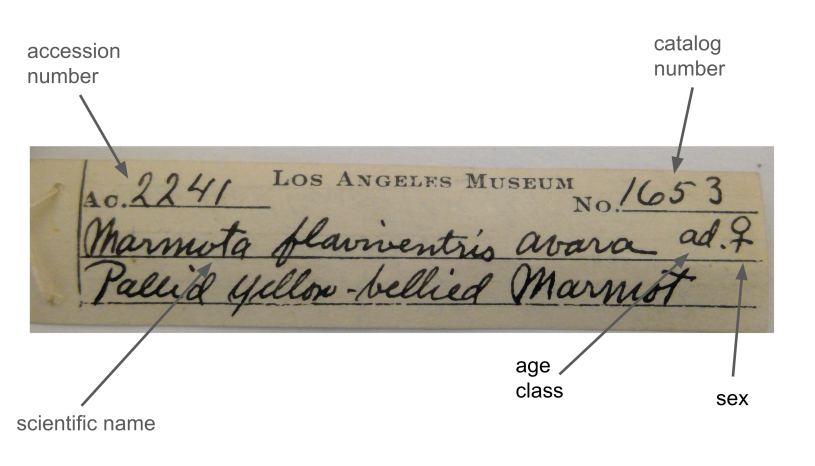

“Traits in this instance are any physical characteristic,” says Dr. Kayce Bell, who’s not only NHM’s Curator of Mammalogy but is also a mammal herself. “So that's everything from standard measurements, from total tail length, hind foot, ear, and weight to sex and reproductive condition.” Those traits are stored on specimen tags like the ones below.

The specimens are already invaluable tools for research, but Bell recognized that making more of their information available could increase their usefulness for science. For example, by capturing changes in a given species over time, the data on collection tags lets researchers track how they might be impacted by environmental factors like climate change.

“Those traits are interesting from a climate change perspective just because we know that there's all sorts of different biological responses to different climate scenarios,” says Bell. “One of the well-established trends in mammals is larger body size in cooler climates at higher latitudes or higher altitudes and smaller body size in warmer climates which is lower altitudes and lower latitudes. So with climate change, it's actually been documented in some cases that animals are getting smaller.” Having this data online will let researchers compare it across collections, helping to discover with more certainty how climate change is affecting mammals in Los Angeles and across the globe to help us better understand the threats they face and how we might protect them.

Working with volunteers through the Zooniverse platform, Ranges is focused on 49,500 mammal specimens from the Western United States to digitize trait data on those tags. Digitization might make you think of hi-tech advancements, but in this case, the task is deceptively simple: transcribing the information from the tags onto the website.

While the transcription itself is technically simple—no lasers, 3D computer modeling, or artificial intelligence needed—it still takes a team of volunteers and paid staff to prepare the information on these critters to be uploaded. Led by Assistant Collections Manager Amanda Killian, the Ranges team has to determine which specimens have digitized data, verify that data, photograph the tags, group the images by animal, edit those images, and upload images to Notes from Nature. That’s where you come in.

You can help the scientists of the future (and the mammals they study) by transcribing on Zooniverse! Click here to get started.

Growing the Value of Collections

At the heart of all this digitization is a relatively new way to look at collection specimens—the extended specimen. Open any drawer of the Mammalogy Collection, and you’ll likely find the furry skin and cleaned bones of an individual animal alongside dozens of the same species (depending on the size of the drawer), and that was a specimen for a century, Bell explains. “The extended specimen really just means more data.”

“In the late 80s, they started to realize you could collect more data. So you could take tissues and you could do an assay which is this old school way of doing genetic studies with proteins and then they added onto that with DNA and then viruses, and now things like parasites,” says Bell. Extended specimens mean more data and more data means greater possibilities for more science. The metadata of life recorded in museum collection tags has become increasingly important to untangling complex questions around ecology and conservation on our planet shaped by human-caused climate change, habitat loss, and other factors.

“I record the exact latitude and longitude within three meters of where every single animal was collected and then we can look that up on Google Earth and be like, " That was right next to a stream and that's where we caught this species," says Bell. That information could let future researchers address things like habitat restoration or have a better idea how changes are affecting any given animal population, or any number of possibilities. Every piece of data opens a new avenue of potential research. “It's adding value to the specimens by collecting as much data as we possibly can.”

One of the most powerful things about museum collections is that we can’t predict exactly how they’ll be used in research. The researchers who brought back bats, marmots, and gophers a hundred years ago couldn’t conceive of the research tools we have today or the ecological issues we face. In the same way, we can’t know exactly how future generations will use the collections and their digitized data. We can be sure that more data expands the range of possibilities.