BE ADVISED: On Saturday, February 21, the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum will host the LAFC vs. Inter Miami soccer match. Kickoff is at 6:30 pm. This event will impact traffic, parking, and wayfinding in the area due to street closures. Paid parking for Prehistoric Fight Nights will be offered in the NHM Car Park at Exposition Blvd and Bill Robertson Ln. Please consider riding the Metro E (Expo) Line and exiting at USC/Expo station.

BE ADVISED: The Natural History Museum is not participating in SoCal Museums Free-for-All on Sunday, February 22.

Hidden black and white feathers are the secret behind songbirds' dazzling colors

Colorful songbirds like tanagers use a painterly technique to make their colors pop

How do colorful songbirds like tanagers make their plumage dazzle? With a secret technique shared with painters, black and white layers (of feathers) underneath make the colors extra vibrant.

Published in the journal Science Advances by a team of researchers from Princeton and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, a new study found that colorful songbirds like tanagers, manakins, fairy wrens, cotingas, and more dramatically enhance their brilliant plumage with secret underlayers of white and black plumage—“hidden achromatic feathers”.

“It’s one of those discoveries that you only notice when looking in detail at museum specimens, and that other biologists totally appreciate as soon as we tell them. It’s been right there all along, but no one has noticed,” says Dr. Allison Shultz, Ornithology Curator at Natural History Museum and expert on feather color. “Over the last few years, it’s become apparent that birds are modifying the colors of their feathers in ways that have flown under scientists’ radar for many years. It’s been really exciting in this study to show an additional way that has never been appreciated—by changing what essentially is the color of the base layer that the colorful parts of feathers lay on.”

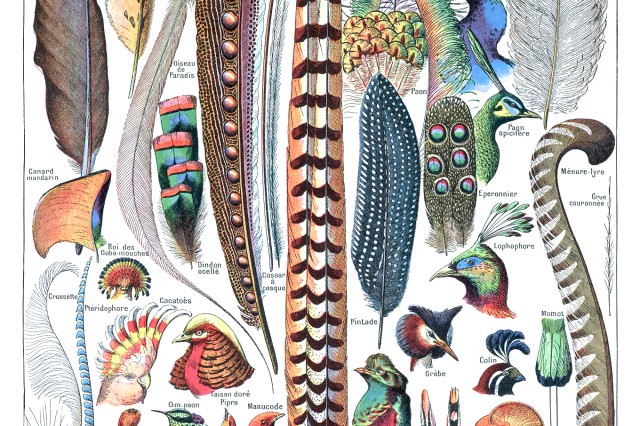

Plumage helps birds find mates, defend territories, and identify members of the same species. It takes thousands of individual feathers overlapping on the body like shingles on a roof to create a smooth and continuous display of color. Individual feathers are generally colorful only at the tip. Beneath the colorful surface of the plumage, the feathers are typically drab, ending in a fluffy, grayish downy base. For decades, researchers assumed the less colorful feather base primarily functions in insulation and has no impact on coloration.

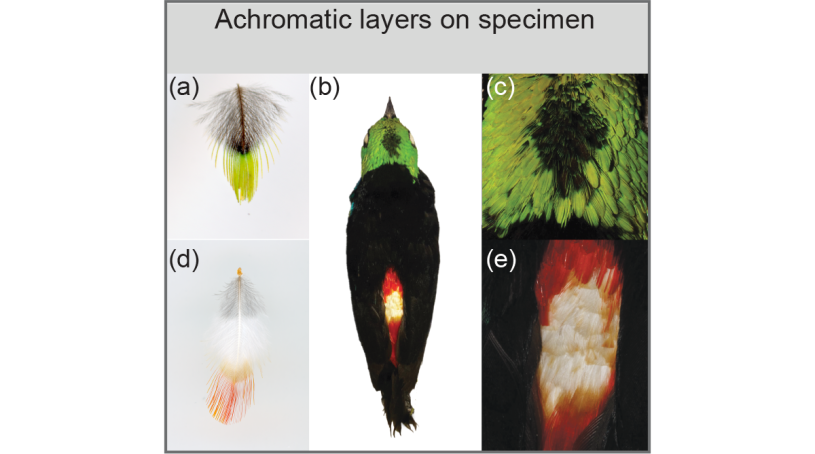

At first, the team noticed the hidden achromatic layers in male Tangara tanagers, a genus of South American songbirds famous for their kaleidoscopic plumage. They examined birds in ornithological collections at NHM, the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, and the Princeton Museum of Zoology with microscopy and photography to document the achromatic layer in Tangara specimens, in some cases removing the colorful feather tips to expose the dramatic white and black layers concealed beneath.

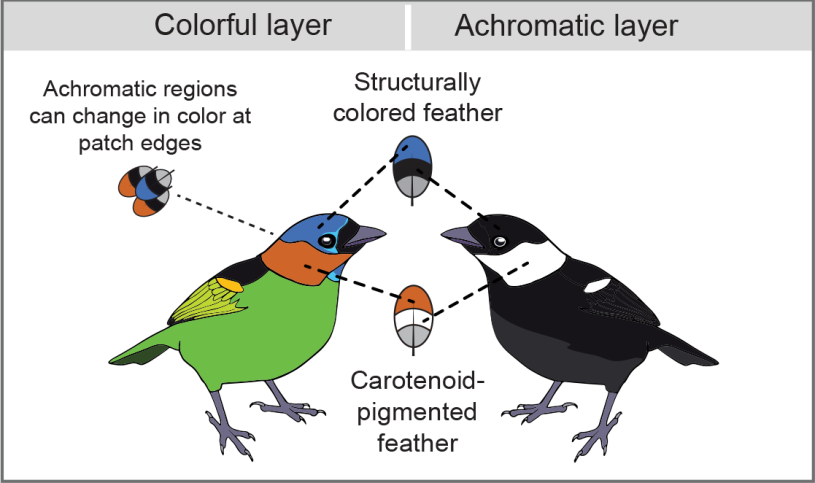

They discovered these hidden layers followed a distinct pattern: white beneath red or yellow feather tips colored by carotenoid pigments—which produce color by absorbing different wavelengths of light—and black beneath blue or violet feather tips colored by nanostructures, whose shape reflects specific wavelengths to produce their colors.

Using a range of state-of-the-art imaging techniques—including multispectral photography, microspectrophotometry, hyperspectral imaging, and optical modeling—to measure how feather tips change in color on white and black backgrounds, they found red and yellow carotenoid plumage is brighter on white backgrounds, while blue structurally colored plumage is more saturated on black backgrounds.

“Tangara females and males tend to look pretty similar, but males usually appear brighter—a phenomenon known as sexual dichromatism,” explains Shultz, and when they compared hidden achromatic layers between males and females, the team found that males had white layers underneath their yellow plumage, but females had black layers. Even more surprisingly, the color of the feathers’ yellow tips was nearly identical between females and males when measured on the same background.

“Without accounting for the effects of white versus black achromatic layers, females and males would look extremely similar,” says Shultz. “That was very unexpected to us. Biologists often assume that sexual dichromatism in reds and yellows is due mostly to the pigment concentration and types in the feather tips. But we found, surprisingly, that these understudied hidden layers can produce substantial and potentially biologically meaningful variation in coloration.”