BE ADVISED: The Natural History Museum is not participating in SoCal Museums Free-for-All on Sunday, February 22.

Spaceport Fossils from French Guiana

How one small step for a spaceport in French Guiana led to a giant leap for Pleistocene fossils

Published March 26, 2024

Every fossil offers a glimpse into the past, but a stunning new fossil site—the first from French Guiana— reveals 130,000 years of regional ecosystems never-before-seen in the fossil record with parallels for our warming present.

Explore the study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA.

This coastal assemblage revealed more than 270 species of animals, plants, and microorganisms from the ancient equatorial Atlantic. Improbably, it was the continued exploration of space that spurred this discovery from Earth’s past—the fossils were uncovered during the construction of the launch pad for the Ariane 6 for Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. From 2017 to 2021, researchers excavated tens of thousands of fossils, spreading the love (and work) among a consortium of paleontologists, geologists, and biologists across the globe—including NHM’s Curator of Invertebrate Paleontology, Dr. Austin Hendy.

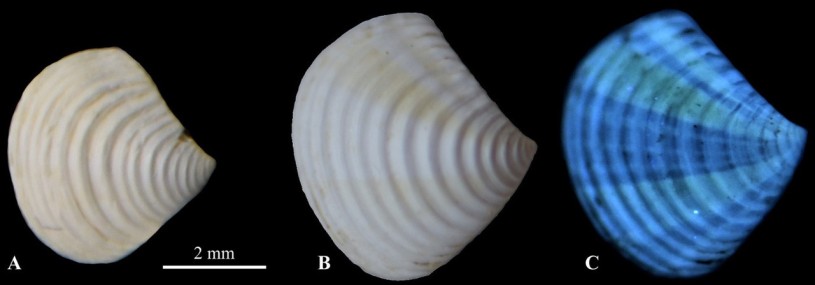

As it’s much more cost-effective to ship tiny shells than a human-sized paleontologist, Hendy’s portion of the work arrived at his office in a box filled with fossil marine invertebrates. With all the anticipation and mystery of opening a gift-wrapped present, he discovered it to contain tens of thousands of mollusk shells, like snails and clams. These turned out to be the most abundant animals in the record, and he immediately recognized them as indicating a shallow marine environment, “much like the mangroves on the coast of French Guiana today.”

"So mollusks are very abundant, but we also have the animals eating the mollusks and it all contributes to build this picture of an ecosystem roughly 120,000 years old." Austin Hendy

Part of what makes the discovery so incredible—beyond the spaceport—is how much of the ancient ecology has been preserved. “All of the ecosystem is represented, from the plants all the way down to little microscopic diatoms,” said Hendy. “So mollusks are very abundant, but we also have the animals eating the mollusks and it all contributes to build this picture of an ecosystem roughly 120,000 years old. So that's pretty cool.”

Ice Age Tropics?

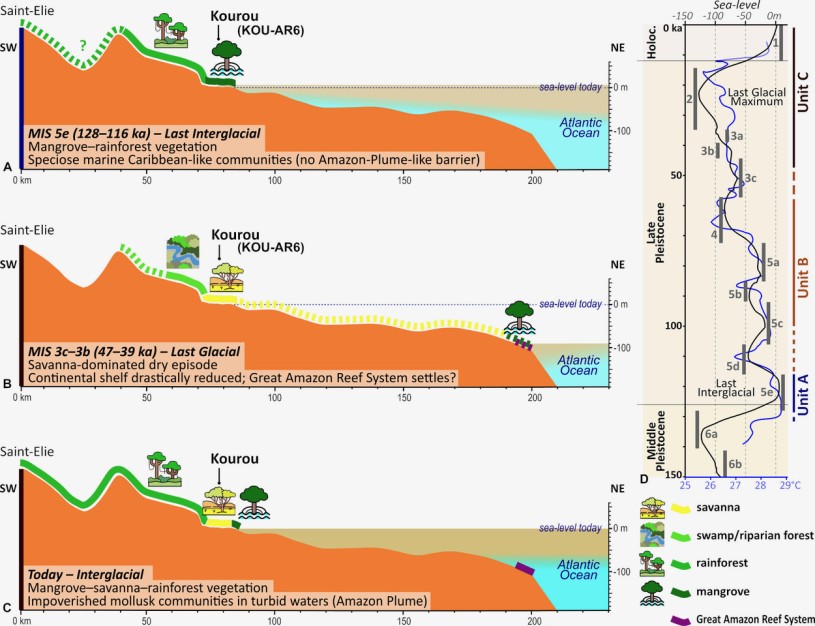

When you think of the Pleistocene, you’re probably thinking of the Ice Age—saber-toothed cats or giant sloths and glaciers in the distance—but the Pleistocene (2.58 million to 11,700 years ago) contained multiple ice ages sandwiched between periods of warming that saw higher sea levels as glaciers retreated. The fossils tell the story of life on French Guiana’s coast both during the last glacial stage from 100,000 to 15,000 years ago, and an earlier much warmer period from 128,000 to 116,000 years ago—the last interglacial. That warming period reflects temperatures in line with predicted human-caused climate change in our not-too-distant future.

“I think it's important because that environment is changing, like many low-lying coastal areas around the world. It's subject to sea level rise, and sensitive to climatic warming, right? When these fossils were deposited it was a little bit warmer than today, so it's kind of a window into what the next hundred years is going to look like,” said Hendy.

From sharks to mollusks, every fossil specimen found represents existing species—some of which are critically endangered. The specimens help us better understand how they lived during a time of parallel heating and elevated sea levels and could help us protect them as human-caused warming impacts the region and the globe.

A New Fossil Frontier

“In a good part of South America, there should not be any fossils,” said Hendy, noting that both the geology and landscape make fossils exceedingly rare in many parts of the continent. Much of it is metavolcanic rock—formed from magma more than a billion years ago. Such settings do not provide the environments needed to preserve and fossilize life from the distant past. “It's not just the geology, it's also the lush rainforest and mangrove swamps, a lack of road outcrops, and beach cliffs. This all makes paleontology more challenging” said Hendy. But this unlikely discovery also points to the possibility of more fossils waiting to be unearthed in the region.

While he continues to expand NHM’s Invertebrate Paleontology Collections, Hendy's focused on growing them in line with the Museum’s mission of being of, for, and with L.A., which means hunting for fossils at sites closer to home, like Palos Verdes. While the Museum will provide the mollusk expert, the mollusks (and other fossils) will be cared for either by affiliated foreign institutions or more ideally local institutions when possible—either France or French Guiana in this case.

As someone committed to supporting researchers local to dig sites and discoveries, he was happy to see that of the international team, six of the 31 researchers were from French Guiana. “Three of them are named Pierre, which made communication a little confusing,” Hendy said. “13 countries were represented as well—truly a diverse and international team.”

The size and scope of the consortium meant that all aspects of the ancient ecosystem could be studied and written up simultaneously, in a single paper, recreating life on French Guiana’s coast during the last glacial and warming period for the first time. That team will stick together as the project moves forward, digging deeper into the fossils’ story for clues about our future. “How different is it from today? Can we make any projections for the future? And I would say at this point that the findings are a little limited to say too much on that but that's why this next phase of the study is going to be quite important,” said Hendy.