Their Worlds and Ours

Rewind the clock and peek into the collections from NHM and La Brea Tar Pits to discover how shifts in climate and habitats over time have impacted Earth’s creatures–including us.

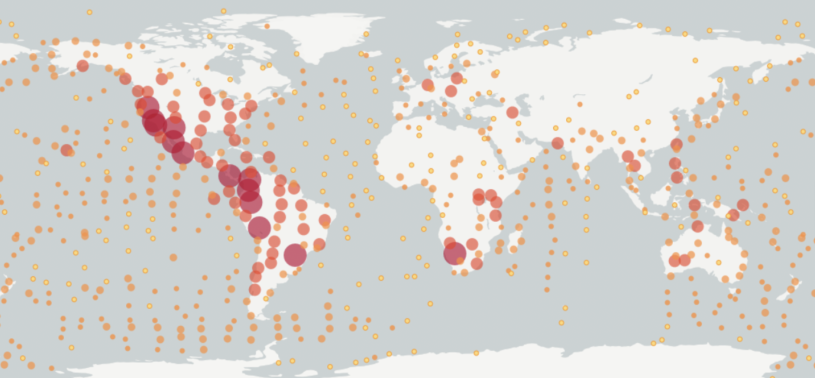

Museum collections are an unparalleled resource tool in our attempts to understand global change and its effects on humans and other species. Our objects and specimens are a historical archive that provides records of biodiversity, human cultures, and earth history to researchers worldwide.

Our collections let researchers rewind the clock to track environmental change and see how shifts in climate, urbanization, land use, and other changes have affected life on our planet. They also let us look forward and sketch future prospects, forecasting weather and how the world will be vulnerable to additional human-generated change.

We asked staff from our Research and Collections Departments to pick objects and specimens from the hundreds of thousands inside cabinets and collections rooms and tell us about their selection.

Ornithology

Submitted by Allison Shultz

The California quail, our state bird, is widespread in oak woodlands, scrub habitats, and grassy savannas, but is not commonly found in urban or urbanizing areas. As urbanization increases, unless they can adapt, they will be increasingly impacted. I chose this specimen because it was collected in 1897 in Pasadena, which looked very different back then. Museum specimens like these show where animals like the California Quail used to live if no longer found in a particular area.

Submitted by Allison Shultz

Cooper’s hawks are an example of an urbanization success story, with the population booming in recent decades following the ban of DDT, an insecticide used in agriculture, and as they have adapted to living with humans. Recent research by our department and UCLA has shown that small hawks with fairly general dietary preferences tend to be particularly successful at living with humans. I chose this specimen because it is a fairly recent addition to our collection, and is an example of how we can grow our collection by salvaging birds that have already died. It is essential that we continue to document not only species in trouble, but success stories so that we can understand what aspects of their ecology or evolution have contributed to that success.

Submitted by Allison Shultz

Museum specimens are now being used in ways their original collectors never could have imagined. For example, traditional study skins are not just sources of trait data, but also of genetic data. Scientists can extract DNA from study skins like this California condor. This is particularly important because this can provide a look at the genetics of a species from the past. I chose this condor, collected in 1898, because it’s been used to help researchers understand how much genetic variation was lost when there were only 22 condors left in the 1980s.

1 of 1

The California quail, our state bird, is widespread in oak woodlands, scrub habitats, and grassy savannas, but is not commonly found in urban or urbanizing areas. As urbanization increases, unless they can adapt, they will be increasingly impacted. I chose this specimen because it was collected in 1897 in Pasadena, which looked very different back then. Museum specimens like these show where animals like the California Quail used to live if no longer found in a particular area.

Submitted by Allison Shultz

Cooper’s hawks are an example of an urbanization success story, with the population booming in recent decades following the ban of DDT, an insecticide used in agriculture, and as they have adapted to living with humans. Recent research by our department and UCLA has shown that small hawks with fairly general dietary preferences tend to be particularly successful at living with humans. I chose this specimen because it is a fairly recent addition to our collection, and is an example of how we can grow our collection by salvaging birds that have already died. It is essential that we continue to document not only species in trouble, but success stories so that we can understand what aspects of their ecology or evolution have contributed to that success.

Submitted by Allison Shultz

Museum specimens are now being used in ways their original collectors never could have imagined. For example, traditional study skins are not just sources of trait data, but also of genetic data. Scientists can extract DNA from study skins like this California condor. This is particularly important because this can provide a look at the genetics of a species from the past. I chose this condor, collected in 1898, because it’s been used to help researchers understand how much genetic variation was lost when there were only 22 condors left in the 1980s.

Submitted by Allison Shultz

Mammalogy

Submitted by Kayce Bell

Mohave ground squirrels (Xerospermophilus mohavensis) are only found in the northwestern portion of the Mojave Desert in California and have lost much of their habitat to development. DNA from specimens like this one help us understand how barriers (such as cities) to movement can impact populations and the levels of population diversity. This specimen is from Palmdale, an area where there are no more Mohave ground squirrels due to human development and habitat loss. This specimen can be used to learn about the squirrels that used to live there.

Submitted by Kayce Bell

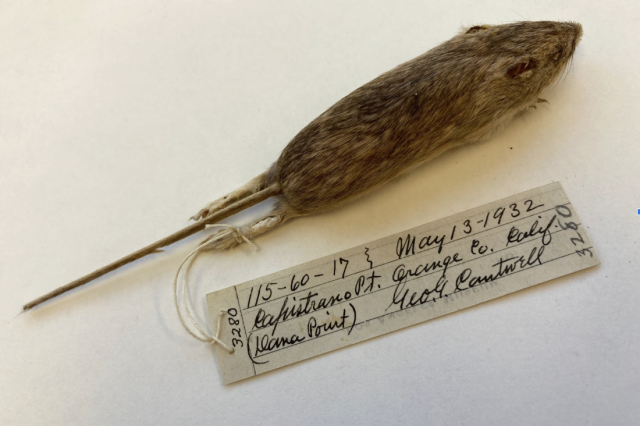

The Pacific pocket mouse (Perognathus longimembris pacificus) used to be common throughout much of Southern California, but it has lost so much habitat that there are only a few populations left. In fact, they were thought to be extinct in the 1970’s but a small remnant population was discovered in Dana Point in 1994. Today, researchers at the San Diego Zoo are using LACM specimens to determine which genetic groups lived in certain areas so that a breeding and reintroduction program can release mice with similar genetic traits in areas where they are not currently found.

Look at this specimen's cheek pockets! Pocket mice are named this because they have an external fur-lined cheek pouch, very similar to a pocket gopher. They are closely related to kangaroo rats and more closely related to pocket gophers than they are to other types of mice, such as the house mouse or deer mouse.

Submitted by Kayce Bell

Museum specimens serve as records of biodiversity in a specific place at a specific time. Researchers have compared historic records (from the early 1900’s) of species occurrences to where they happen today and have found that climate change has impacted some species ranges in the Sierra Nevada. An example of this includes the lodgepole chipmunk, which hasn’t changed its distribution much since the early 20th Century; however, climate change seems to have had a drastic impact. Current populations of alpine chipmunks are restricted to higher elevations and have limited ability to disperse due to the climate and habitat being at lower and inhospitable elevations. I chose this specimen because I study chipmunks and their parasites. Not only can we use these specimens to understand how their populations have changed over time, but I can also recover parasitic sucking lice from the skins to study how the parasites may have changed as well.

1 of 1

Mohave ground squirrels (Xerospermophilus mohavensis) are only found in the northwestern portion of the Mojave Desert in California and have lost much of their habitat to development. DNA from specimens like this one help us understand how barriers (such as cities) to movement can impact populations and the levels of population diversity. This specimen is from Palmdale, an area where there are no more Mohave ground squirrels due to human development and habitat loss. This specimen can be used to learn about the squirrels that used to live there.

Submitted by Kayce Bell

The Pacific pocket mouse (Perognathus longimembris pacificus) used to be common throughout much of Southern California, but it has lost so much habitat that there are only a few populations left. In fact, they were thought to be extinct in the 1970’s but a small remnant population was discovered in Dana Point in 1994. Today, researchers at the San Diego Zoo are using LACM specimens to determine which genetic groups lived in certain areas so that a breeding and reintroduction program can release mice with similar genetic traits in areas where they are not currently found.

Look at this specimen's cheek pockets! Pocket mice are named this because they have an external fur-lined cheek pouch, very similar to a pocket gopher. They are closely related to kangaroo rats and more closely related to pocket gophers than they are to other types of mice, such as the house mouse or deer mouse.

Submitted by Kayce Bell

Museum specimens serve as records of biodiversity in a specific place at a specific time. Researchers have compared historic records (from the early 1900’s) of species occurrences to where they happen today and have found that climate change has impacted some species ranges in the Sierra Nevada. An example of this includes the lodgepole chipmunk, which hasn’t changed its distribution much since the early 20th Century; however, climate change seems to have had a drastic impact. Current populations of alpine chipmunks are restricted to higher elevations and have limited ability to disperse due to the climate and habitat being at lower and inhospitable elevations. I chose this specimen because I study chipmunks and their parasites. Not only can we use these specimens to understand how their populations have changed over time, but I can also recover parasitic sucking lice from the skins to study how the parasites may have changed as well.

Submitted by Kayce Bell

Ichthyology

Submitted by Bill Ludt

These two tiny specimens may not look like much, but they are extremely important. These are juvenile Chinese paddlefishes, which were declared extinct in 2019. This species was native to the Yangtze and Yellow River basins and could grow to over 10 feet in length, but overfishing and changes to the flow of the river by dam construction led to their demise. Museums with large global collections, like our own, are the only way that scientists can study species that are no longer present on our planet and give us perspective on our impact on the natural world. I chose these specimens because they represent the worst-case scenario of global change: extinction. However, they also highlight the importance of broad, global museum collections as the only place to study extinct species.

Submitted by Bill Ludt

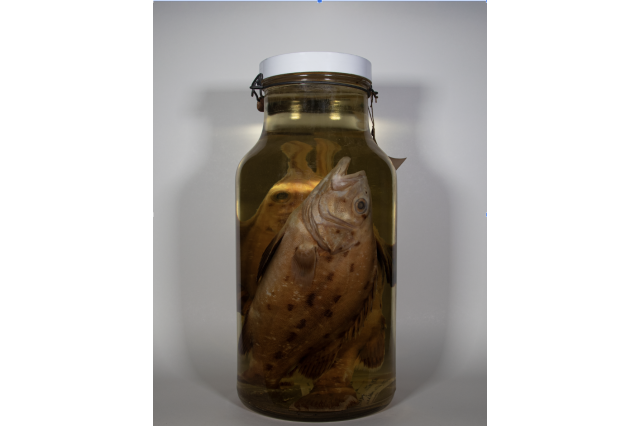

These are two juvenile giant sea bass, one of the most charismatic large fishes along the California coast. This species can grow to massive sizes, exceeding 7 feet in length and weighing more than 500 pounds at their largest. Once imperiled due to overfishing, this species is now making a comeback and represents how it is possible to make positive environmental changes to correct for problems we made in the past. I chose this species because it showcases that while there are many anthropogenic influences that negatively impact wildlife, we can also make positive changes if we collectively coordinate quick responses to at-risk species.

1 of 1

These two tiny specimens may not look like much, but they are extremely important. These are juvenile Chinese paddlefishes, which were declared extinct in 2019. This species was native to the Yangtze and Yellow River basins and could grow to over 10 feet in length, but overfishing and changes to the flow of the river by dam construction led to their demise. Museums with large global collections, like our own, are the only way that scientists can study species that are no longer present on our planet and give us perspective on our impact on the natural world. I chose these specimens because they represent the worst-case scenario of global change: extinction. However, they also highlight the importance of broad, global museum collections as the only place to study extinct species.

Submitted by Bill Ludt

These are two juvenile giant sea bass, one of the most charismatic large fishes along the California coast. This species can grow to massive sizes, exceeding 7 feet in length and weighing more than 500 pounds at their largest. Once imperiled due to overfishing, this species is now making a comeback and represents how it is possible to make positive environmental changes to correct for problems we made in the past. I chose this species because it showcases that while there are many anthropogenic influences that negatively impact wildlife, we can also make positive changes if we collectively coordinate quick responses to at-risk species.

Submitted by Bill Ludt

Anthropology

![Salmon mask by Richard Hunt [Kwakiutl/Kwagiutl (Kwakwaka'wakw)], 2008. Vancouver Island, British Columbia. NHM# F.P.4.2009-26](/sites/default/files/styles/asp_switcher_4_3_med/public/2023-03/Salmon%20mask_Anthropology.jpg)

Submitted by KT Hajeian

Studies show that climate change is leading to declines in salmon populations off the coast of western Canada. A report authored by researchers of British Columbia stated that unless the pace of temperature change slows, about half of the Indigenous fisheries will be lost by 2050. For First Nations peoples who have commercially, culturally, and nutritionally relied on salmon for thousands of years, this decline has major implications for the preservation of their traditions. I chose this item because by literally surrounding the central face with salmon, the artist effectively conveys the significance salmon play in the livelihood of his Kwakiutl/Kwagiutl (Kwakwaka'wakw) community.

Salmon mask by Richard Hunt [Kwakiutl/Kwagiutl (Kwakwaka'wakw)], 2008. Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

Submitted by KT Hajeian

Unexpected changes in environmental patterns greatly impact the lifestyles of pastoral peoples around the world by influencing the behavior and migration patterns of their herds. In Kenya, where severe droughts have depleted water and available land for pasture, many pastoralists are resorting to swapping their long tradition of herding cattle to herding other animals like goats, sheep, and camels who are better equipped at withstanding erratic weather. I chose this cow bell used by a Masai/Massai herder in Kenya because even an unexceptional or commonplace item may come to represent a tradition no longer seen in action.

Submitted by Chris Coleman

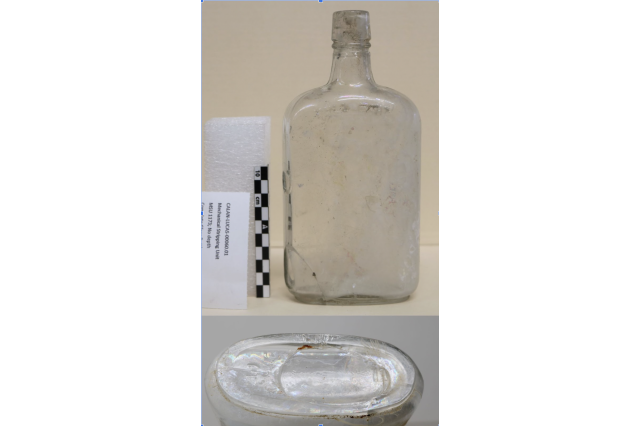

This Dandy Flask (circa 1905-1919 made by the Boldt Glass Co.) from the Lucas Museum site originally contained whiskey. It is an early example of a glass container made by the Owens Automatic Bottling Machine indicated by the basal oval scar. This mechanized method revolutionized the manufacture of glass containers that led to their mass production which has caused major environmental and recycling problems today. I chose this specimen because I am interested in historic glass technology and how historic collections can be used to discuss current events.

1 of 1

Studies show that climate change is leading to declines in salmon populations off the coast of western Canada. A report authored by researchers of British Columbia stated that unless the pace of temperature change slows, about half of the Indigenous fisheries will be lost by 2050. For First Nations peoples who have commercially, culturally, and nutritionally relied on salmon for thousands of years, this decline has major implications for the preservation of their traditions. I chose this item because by literally surrounding the central face with salmon, the artist effectively conveys the significance salmon play in the livelihood of his Kwakiutl/Kwagiutl (Kwakwaka'wakw) community.

Salmon mask by Richard Hunt [Kwakiutl/Kwagiutl (Kwakwaka'wakw)], 2008. Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

Submitted by KT Hajeian

Unexpected changes in environmental patterns greatly impact the lifestyles of pastoral peoples around the world by influencing the behavior and migration patterns of their herds. In Kenya, where severe droughts have depleted water and available land for pasture, many pastoralists are resorting to swapping their long tradition of herding cattle to herding other animals like goats, sheep, and camels who are better equipped at withstanding erratic weather. I chose this cow bell used by a Masai/Massai herder in Kenya because even an unexceptional or commonplace item may come to represent a tradition no longer seen in action.

Submitted by KT Hajeian

This Dandy Flask (circa 1905-1919 made by the Boldt Glass Co.) from the Lucas Museum site originally contained whiskey. It is an early example of a glass container made by the Owens Automatic Bottling Machine indicated by the basal oval scar. This mechanized method revolutionized the manufacture of glass containers that led to their mass production which has caused major environmental and recycling problems today. I chose this specimen because I am interested in historic glass technology and how historic collections can be used to discuss current events.

Submitted by Chris Coleman

Dinosaur Institute

Submitted by Nate Smith

Two hundred fifty million years ago, the Earth was just recovering from the greatest mass extinction of all time, and our distant relative, the weasel-sized Thrinaxodon, was scurrying around Antarctica. During a 2017–18 expedition to the Shackleton Glacier region, Nate Smith and colleagues collected this skeleton, as well as hundreds of other vertebrate fossils that will help us understand how communities in polar regions differed from their low-latitude neighbors, and how they responded to large-scale climate change. I chose this specimen because of the deep-time perspective it offers on life in polar regions, as well as for the critical role our fossil record plays in contextualizing our understanding of modern biotic responses to climate change.

1 of 1

Two hundred fifty million years ago, the Earth was just recovering from the greatest mass extinction of all time, and our distant relative, the weasel-sized Thrinaxodon, was scurrying around Antarctica. During a 2017–18 expedition to the Shackleton Glacier region, Nate Smith and colleagues collected this skeleton, as well as hundreds of other vertebrate fossils that will help us understand how communities in polar regions differed from their low-latitude neighbors, and how they responded to large-scale climate change. I chose this specimen because of the deep-time perspective it offers on life in polar regions, as well as for the critical role our fossil record plays in contextualizing our understanding of modern biotic responses to climate change.

Submitted by Nate Smith

Museum Archives

Submitted by Cyrene Cruz

In the 1960s, NHMLAC took part in “Operation Oryx,” an international effort to establish captive breeding programs focused on returning nearly extinct Oryx populations to their native habitats in Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Oman. While the Arabian Oryx is still listed as endangered, they are no longer considered to be extinct in the wild. NHM worked with the L.A., San Diego, and Phoenix Zoos as a repository for Oryx specimens that died in captivity. I chose this object because it emphasizes long-term connections between conservation, zoos, and museums.

1 of 1

In the 1960s, NHMLAC took part in “Operation Oryx,” an international effort to establish captive breeding programs focused on returning nearly extinct Oryx populations to their native habitats in Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Oman. While the Arabian Oryx is still listed as endangered, they are no longer considered to be extinct in the wild. NHM worked with the L.A., San Diego, and Phoenix Zoos as a repository for Oryx specimens that died in captivity. I chose this object because it emphasizes long-term connections between conservation, zoos, and museums.

Submitted by Cyrene Cruz

La Brea Tar Pits

The fossils at La Brea Tar Pits provide us an amazingly detailed window into the past, and with it, an extraordinary opportunity to study how a past climate change event impacted the plant and animal communities under conditions that were very similar to today. So similar, in fact, that many of the plant and animal species we find at the tar pits still exist in or near the Los Angeles basin today. At the end of the last ice age (~14,000 years ago) the climate became much warmer and drier than it had been before, very similar to what we are experiencing today. That means that paleontological research at La Brea isn’t just about understanding the past, but also about leveraging the past to understand the future.

Two fossilized juniper seeds from La Brea Tar Pits

Submitted by Emily Lindsey and Danaan DeNeve Weeks

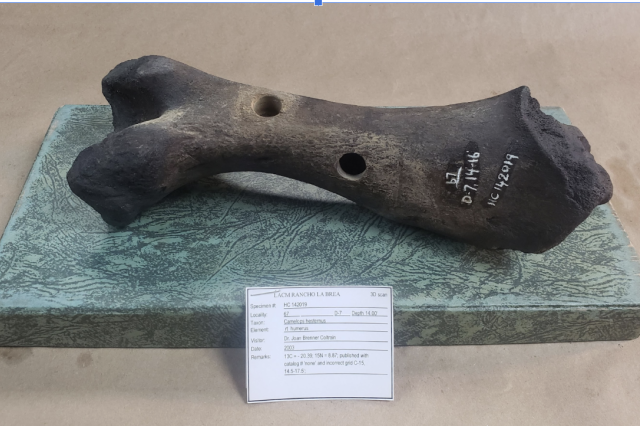

This is the upper arm bone of the last Western Camel (Camelops hesternus) that lived at La Brea. We know from radiocarbon dating (the bore holes in the bone are from the radiocarbon dating process) that this camel lived at La Brea 13,700 years ago, making it the most recent camel fossil we have from the Tar Pits before camels were extirpated from the L.A. Basin and, eventually, from North America. Camels disappear from the fossil record almost a thousand years earlier than the other megafauna, very early in the period of warming and drying. It may be odd to think of a camel going extinct because the climate became hot and dry, but in this case it had more to do with the associated vegetation changes than the camel’s climatic tolerance. As the climate aridified, grasslands proliferated across the western United States. While this was beneficial to some large herbivores, such as horses and bison, it wasn’t so great for camels, animals that primarily browsed on the trees and shrubs that were giving way to grassland. We chose this specimen because this was one of the last members of its species to live in Los Angeles.

Submitted by Mairin Balisi and Danaan DeNeve Weeks

When we think about fossils from La Brea, we usually think of megafauna, and we usually think of extinction. But there is also a story of survival, and of change. These are two of the arm bones of an American Badger. The white bones are those of a modern badger from the LA Basin, and the brown ones are from a fossil badger from the tar pits. Toward the end of the last ice age, badgers appeared in the L.A. Basin, and while they were the same species as modern badgers, they wouldn’t have looked quite the same. The fossils indicate that badgers occupying this region in the early Holocene had longer and more robust forearms and more robust jaws than modern southern California badgers, adaptations suggesting they were better diggers and more carnivorous than modern badgers in this area. The timing and the morphological changes suggest that badgers were responding to environmental change, but there are still a lot of questions, such as: what was keeping them out of this area before, why did they need to be better diggers, and how might they have changed in diet and behavior from then to now?

1 of 1

The fossils at La Brea Tar Pits provide us an amazingly detailed window into the past, and with it, an extraordinary opportunity to study how a past climate change event impacted the plant and animal communities under conditions that were very similar to today. So similar, in fact, that many of the plant and animal species we find at the tar pits still exist in or near the Los Angeles basin today. At the end of the last ice age (~14,000 years ago) the climate became much warmer and drier than it had been before, very similar to what we are experiencing today. That means that paleontological research at La Brea isn’t just about understanding the past, but also about leveraging the past to understand the future.

Two fossilized juniper seeds from La Brea Tar Pits

This is the upper arm bone of the last Western Camel (Camelops hesternus) that lived at La Brea. We know from radiocarbon dating (the bore holes in the bone are from the radiocarbon dating process) that this camel lived at La Brea 13,700 years ago, making it the most recent camel fossil we have from the Tar Pits before camels were extirpated from the L.A. Basin and, eventually, from North America. Camels disappear from the fossil record almost a thousand years earlier than the other megafauna, very early in the period of warming and drying. It may be odd to think of a camel going extinct because the climate became hot and dry, but in this case it had more to do with the associated vegetation changes than the camel’s climatic tolerance. As the climate aridified, grasslands proliferated across the western United States. While this was beneficial to some large herbivores, such as horses and bison, it wasn’t so great for camels, animals that primarily browsed on the trees and shrubs that were giving way to grassland. We chose this specimen because this was one of the last members of its species to live in Los Angeles.

Submitted by Emily Lindsey and Danaan DeNeve Weeks

When we think about fossils from La Brea, we usually think of megafauna, and we usually think of extinction. But there is also a story of survival, and of change. These are two of the arm bones of an American Badger. The white bones are those of a modern badger from the LA Basin, and the brown ones are from a fossil badger from the tar pits. Toward the end of the last ice age, badgers appeared in the L.A. Basin, and while they were the same species as modern badgers, they wouldn’t have looked quite the same. The fossils indicate that badgers occupying this region in the early Holocene had longer and more robust forearms and more robust jaws than modern southern California badgers, adaptations suggesting they were better diggers and more carnivorous than modern badgers in this area. The timing and the morphological changes suggest that badgers were responding to environmental change, but there are still a lot of questions, such as: what was keeping them out of this area before, why did they need to be better diggers, and how might they have changed in diet and behavior from then to now?

Submitted by Mairin Balisi and Danaan DeNeve Weeks

Polychaetes

Submitted by Leslie Harris

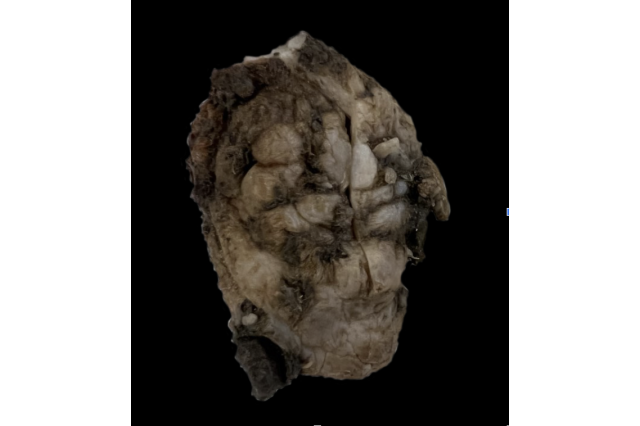

A rare sight nowadays—the sea worm Placostegus californicus (the white tubes) is living on the large red lampshell Laqueus erythraeus. These shells and their hitchhikers live attached to rocks and were once common off Southern California. See the next photo for an explanation.

Submitted by Leslie Harris

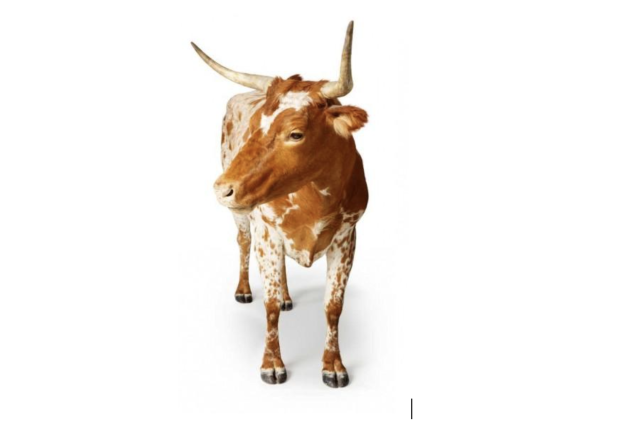

Our Becoming Los Angeles exhibit with its taxidermied cow represents the rancho era and the reason that today this lampshell and its sea worm are rare. Not only did the cows overgraze the landscape allowing non-native grasses to proliferate, sediment run-off from the ground they trampled covered the rocky sea bottom with thick layers of silt. Reefs that the lampshells and worms depended on disappeared thanks to the cows of Los Angeles. I chose this because of how well it demonstrates the often surprising results of human activities in the natural world.

Submitted by Leslie Harris

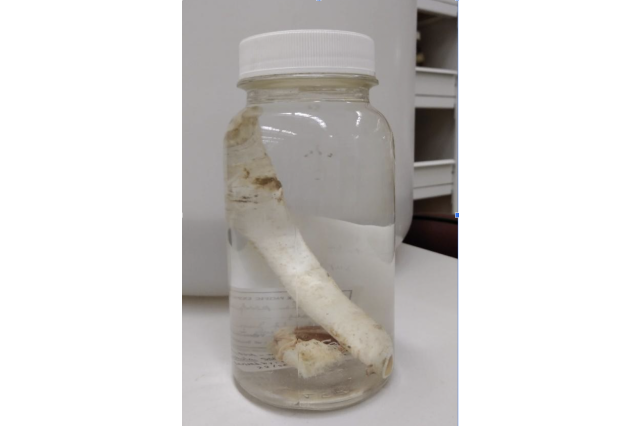

The oldest of these calcium carbonate polychaete worm tubes is nearly 4,000 years old. Fossils are the preserved remains of organisms, but all fossils begin with living specimens and this species persists today. These specimens are old, but old is relative, hence many biologists would call these subfossils, “fossils in the making”. Researchers have examined subfossil and modern tubes from our collection and compared their elemental composition through time. One interesting result is that modern tubes found near sewer outfalls, hypothesized to have higher levels of anthropogenically derived metals, had similar levels to the subfossil tubes. I chose these because they illustrate why we sometimes retain objects that to many may seem to have little value. Empty tubes are normally discarded when sampling the ocean, but even the humblest museum specimen can reveal information useful for understanding our effect on the world around us. The Museum specimen above is Protula superba.

1 of 1

A rare sight nowadays—the sea worm Placostegus californicus (the white tubes) is living on the large red lampshell Laqueus erythraeus. These shells and their hitchhikers live attached to rocks and were once common off Southern California. See the next photo for an explanation.

Submitted by Leslie Harris

Our Becoming Los Angeles exhibit with its taxidermied cow represents the rancho era and the reason that today this lampshell and its sea worm are rare. Not only did the cows overgraze the landscape allowing non-native grasses to proliferate, sediment run-off from the ground they trampled covered the rocky sea bottom with thick layers of silt. Reefs that the lampshells and worms depended on disappeared thanks to the cows of Los Angeles. I chose this because of how well it demonstrates the often surprising results of human activities in the natural world.

Submitted by Leslie Harris

The oldest of these calcium carbonate polychaete worm tubes is nearly 4,000 years old. Fossils are the preserved remains of organisms, but all fossils begin with living specimens and this species persists today. These specimens are old, but old is relative, hence many biologists would call these subfossils, “fossils in the making”. Researchers have examined subfossil and modern tubes from our collection and compared their elemental composition through time. One interesting result is that modern tubes found near sewer outfalls, hypothesized to have higher levels of anthropogenically derived metals, had similar levels to the subfossil tubes. I chose these because they illustrate why we sometimes retain objects that to many may seem to have little value. Empty tubes are normally discarded when sampling the ocean, but even the humblest museum specimen can reveal information useful for understanding our effect on the world around us. The Museum specimen above is Protula superba.

Submitted by Leslie Harris

Vertebrate Paleontology

Submitted by Juliet Hook and Sam McLeod

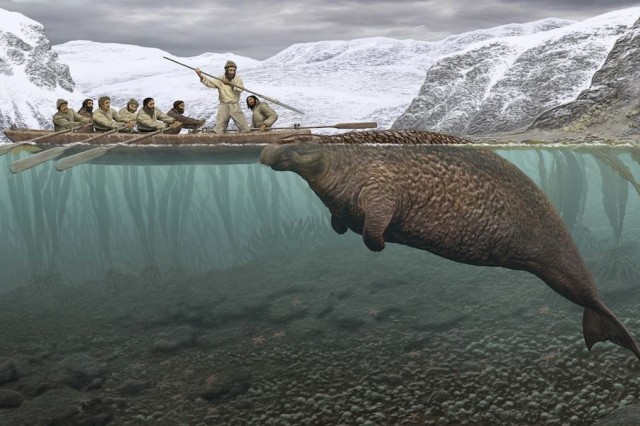

Steller’s sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas), first noted by the European explorer Georg Wilhelm Steller in 1741, swam in docile, bonded packs around the Commander Islands between Russia and Alaska. By 1768, this dugong relative, amongst the largest herbivorous mammals of all time, had been hunted to extinction for meat, oil, and clothing by Russian hunters and explorers.

Submitted by Juliet Hook and Sam McLeod

This skull of a sister species, Hydrodamalis cuestae, in our collection represents a former much greater range for this peculiar marine mammal during differing climatic conditions. The 27 year extinction of the Steller’s sea cow exemplifies the rapid effects of human-generated change and the extreme vulnerability of species to our lifestyle needs and choices. We selected this story because it highlights the sad and tragic consequences, even if unintended, of our actions.

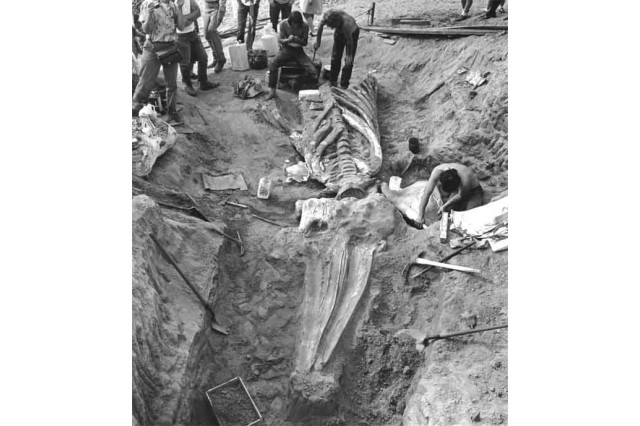

Submitted by Juliet Hook and Sam McLeod

This is a field photo depicting the excavation of a fossil gray whale (Eschrichtius) skull and skeleton that was discovered in the San Pedro area of Los Angeles County in 1971. When this whale was alive, perhaps 80,000 to 100,000 years ago, sea levels were much higher in Los Angeles County and the area of the fossil discovery was under water during different climatic conditions. Fossil specimens provide an opportunity to study extinct animals as well as the environment, ecosystem, and climate in which they once lived. With this knowledge of sea level fluctuation, researchers can study how extinct species adapted and evolved to changes in the environment which can help predict and guide conservation efforts for extant animals in today's changing global landscape.

We chose this specimen because of its discovery in Los Angeles and for the rare nature of this beautifully preserved specimen. Intact or nearly complete fossil whale skeletons are uncommon and gray whale fossils are rare.

1 of 1

Steller’s sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas), first noted by the European explorer Georg Wilhelm Steller in 1741, swam in docile, bonded packs around the Commander Islands between Russia and Alaska. By 1768, this dugong relative, amongst the largest herbivorous mammals of all time, had been hunted to extinction for meat, oil, and clothing by Russian hunters and explorers.

Submitted by Juliet Hook and Sam McLeod

This skull of a sister species, Hydrodamalis cuestae, in our collection represents a former much greater range for this peculiar marine mammal during differing climatic conditions. The 27 year extinction of the Steller’s sea cow exemplifies the rapid effects of human-generated change and the extreme vulnerability of species to our lifestyle needs and choices. We selected this story because it highlights the sad and tragic consequences, even if unintended, of our actions.

Submitted by Juliet Hook and Sam McLeod

This is a field photo depicting the excavation of a fossil gray whale (Eschrichtius) skull and skeleton that was discovered in the San Pedro area of Los Angeles County in 1971. When this whale was alive, perhaps 80,000 to 100,000 years ago, sea levels were much higher in Los Angeles County and the area of the fossil discovery was under water during different climatic conditions. Fossil specimens provide an opportunity to study extinct animals as well as the environment, ecosystem, and climate in which they once lived. With this knowledge of sea level fluctuation, researchers can study how extinct species adapted and evolved to changes in the environment which can help predict and guide conservation efforts for extant animals in today's changing global landscape.

We chose this specimen because of its discovery in Los Angeles and for the rare nature of this beautifully preserved specimen. Intact or nearly complete fossil whale skeletons are uncommon and gray whale fossils are rare.

Submitted by Juliet Hook and Sam McLeod

Seaver Center for Western History Research

Submitted by Betty Uyeda

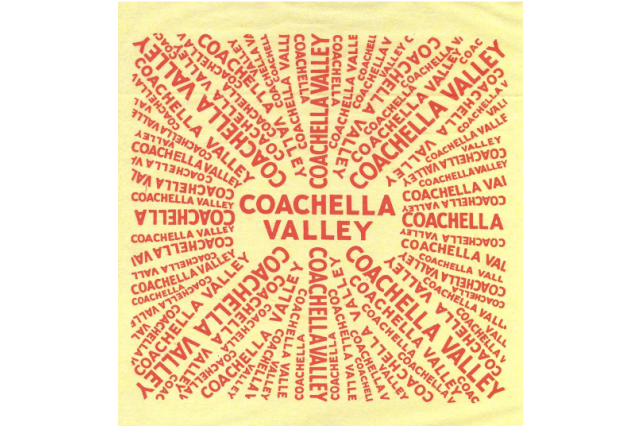

Shown is a produce wrapper from the Coachella Valley agricultural region of Riverside County. The fields were a landing place for American migrants during the Great Depression and, in later years, for foreigners seeking work. Farming here remains vibrant though on the decline. Long grown here are table grapes and dates which today are top crops in value and acreage. Golf course turf grass is not far behind.

The wrapper is from the Produce Labels Collection (circa late 1920s-early 1930s), and its graphic is eye-catching and playful. Not known is the fruit or vegetable which would have required this packaging. The art design could be misconstrued as advertising for today’s well-known eponymous music and arts festival.

Submitted by Kim Walters

The idea of branding cattle for identifying ownership has been used for millennia. This brand is from San Gabriel Mission dates to around 1780. Earthquakes in 1804 and 1812 that damaged its buildings caused it to be known as the “Mission of Earthquakes.” Since cattle roamed freely it was necessary for the missions to brand their cattle. The TS brand for San Gabriel represents “Temblores” the Spanish word for tremors. (A.110.58.1607)

Submitted by Kim Walters

The padres introduced cattle into the local environment which changed it forever. Excrement from newly arrived cattle from Mexico contained non-native seed material. When this sprouted, many of the native plants could not compete. This situation was made worse following Mexican Independence from Spain when 72 large ranchos were established in what is today Los Angeles, and Orange counties. Above: the brand for the city of Los Angeles.

There were thousands of cattle trampling and grazing on the local vegetation. Each of these ranchos and subsequent ones had their own brands to identify their cattle. These brands were recorded in books like the one illustrated below showing the registration for Antonio Coronel. During the 1800s Los Angeles supplied most of the beef, hides, and tallow in California and the U.S. Today the cattle business is not a prominent economic force in LA County, but the environment has been changed forever. Above: The brand for the City of Los Angeles.

Submitted by John Cahoon

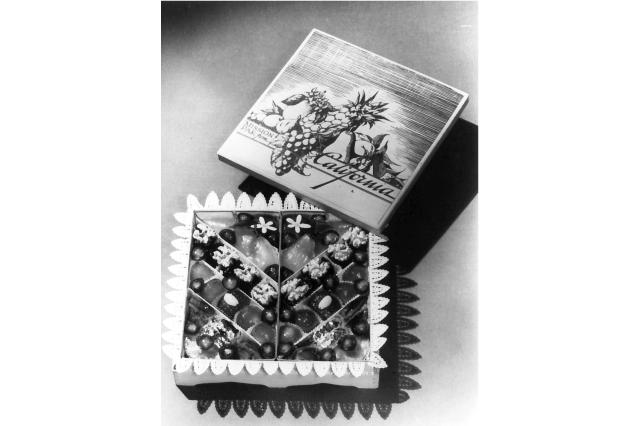

Los Angeles entrepreneur, real estate developer, and philanthropist, George C. Page, is perhaps best known as the benefactor of La Brea Tar Pits in Hancock Park that bears his name. But in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, Americans were more familiar with the company he founded as a 16-year-old: Mission Pak.

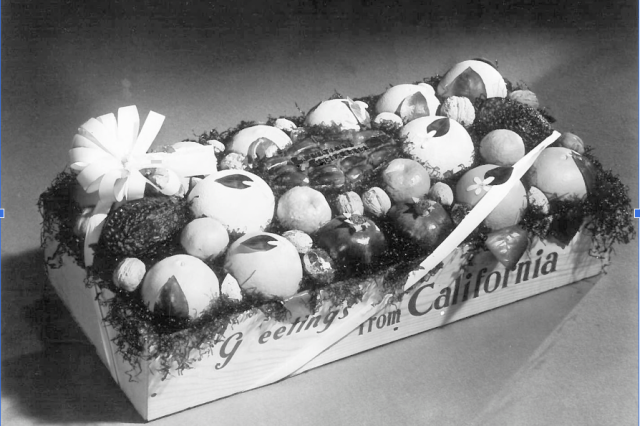

Page pioneered the concept of decoratively packaging California fruits and nuts and shipping them from sunny Southern California to cold weather customers in the east and Midwest. For his first Christmas in California he sent some California fruit in a box with red paper and tinsel to his family in Nebraska. Thirty-seven other roomers in his boarding house were so impressed they had him send packages to their Midwestern relatives too, and Mission Pak was born. Mission Pak recipients back east identified the oranges and walnuts that they received with California. Page himself said when he tasted his first orange at age 12 he hoped someday "I can live where that came from." But the influx of people moving to California over the past century has greatly impacted the agricultural landscape, and orange groves have been replaced by housing developments and shopping malls. And while Southern California produced more that 75% of the state's walnuts when Page arrived, it was less than 15% just 50 years later.

Above: A handsome wooden box featuring the Mission Pak logo top left.

Submitted by John Cahoon

A gift package of oranges and walnuts with "Greetings from California."

Mrs. Julliette Page poses with a very large and elaborate gift basket.

1 of 1

Shown is a produce wrapper from the Coachella Valley agricultural region of Riverside County. The fields were a landing place for American migrants during the Great Depression and, in later years, for foreigners seeking work. Farming here remains vibrant though on the decline. Long grown here are table grapes and dates which today are top crops in value and acreage. Golf course turf grass is not far behind.

The wrapper is from the Produce Labels Collection (circa late 1920s-early 1930s), and its graphic is eye-catching and playful. Not known is the fruit or vegetable which would have required this packaging. The art design could be misconstrued as advertising for today’s well-known eponymous music and arts festival.

Submitted by Betty Uyeda

The idea of branding cattle for identifying ownership has been used for millennia. This brand is from San Gabriel Mission dates to around 1780. Earthquakes in 1804 and 1812 that damaged its buildings caused it to be known as the “Mission of Earthquakes.” Since cattle roamed freely it was necessary for the missions to brand their cattle. The TS brand for San Gabriel represents “Temblores” the Spanish word for tremors. (A.110.58.1607)

Submitted by Kim Walters

The padres introduced cattle into the local environment which changed it forever. Excrement from newly arrived cattle from Mexico contained non-native seed material. When this sprouted, many of the native plants could not compete. This situation was made worse following Mexican Independence from Spain when 72 large ranchos were established in what is today Los Angeles, and Orange counties. Above: the brand for the city of Los Angeles.

There were thousands of cattle trampling and grazing on the local vegetation. Each of these ranchos and subsequent ones had their own brands to identify their cattle. These brands were recorded in books like the one illustrated below showing the registration for Antonio Coronel. During the 1800s Los Angeles supplied most of the beef, hides, and tallow in California and the U.S. Today the cattle business is not a prominent economic force in LA County, but the environment has been changed forever. Above: The brand for the City of Los Angeles.

Submitted by Kim Walters

Los Angeles entrepreneur, real estate developer, and philanthropist, George C. Page, is perhaps best known as the benefactor of La Brea Tar Pits in Hancock Park that bears his name. But in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, Americans were more familiar with the company he founded as a 16-year-old: Mission Pak.

Page pioneered the concept of decoratively packaging California fruits and nuts and shipping them from sunny Southern California to cold weather customers in the east and Midwest. For his first Christmas in California he sent some California fruit in a box with red paper and tinsel to his family in Nebraska. Thirty-seven other roomers in his boarding house were so impressed they had him send packages to their Midwestern relatives too, and Mission Pak was born. Mission Pak recipients back east identified the oranges and walnuts that they received with California. Page himself said when he tasted his first orange at age 12 he hoped someday "I can live where that came from." But the influx of people moving to California over the past century has greatly impacted the agricultural landscape, and orange groves have been replaced by housing developments and shopping malls. And while Southern California produced more that 75% of the state's walnuts when Page arrived, it was less than 15% just 50 years later.

Above: A handsome wooden box featuring the Mission Pak logo top left.

Submitted by John Cahoon

A gift package of oranges and walnuts with "Greetings from California."

Submitted by John Cahoon

Mrs. Julliette Page poses with a very large and elaborate gift basket.

Malacology

Submitted by Lindsey Groves

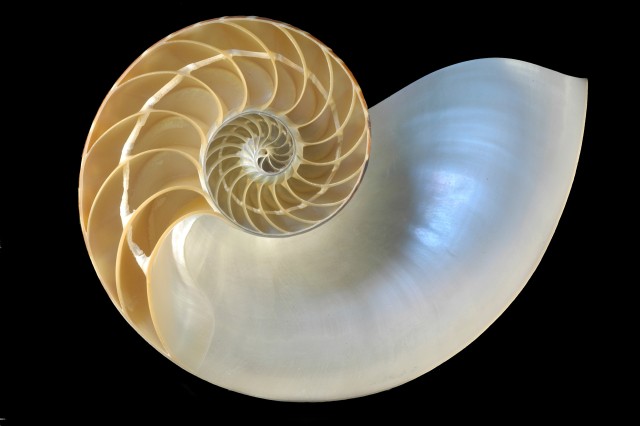

Nautilus pompilius Linnaeus, 1758, Chambered nautilus, Philippines

All invertebrates are threatened by global environmental changes and the chambered nautilus is no exception. They are highly prized by collectors but recently received protection from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) to prevent over-exploitation through international trade.

Submitted by Lindsey Groves

Paupstyla pulcherrima Rensch, 1931, Emerald Green snail, Manus Id., Papua New Guinea: In the past the shells of this species were in demand for making jewelry and were popular with shell collectors. Those factors, plus the fact that their habitat is being destroyed, have led to the species now being considered threatened. Fortunately, it has received protection via CITES.

1 of 1

Nautilus pompilius Linnaeus, 1758, Chambered nautilus, Philippines

All invertebrates are threatened by global environmental changes and the chambered nautilus is no exception. They are highly prized by collectors but recently received protection from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) to prevent over-exploitation through international trade.

Submitted by Lindsey Groves

Paupstyla pulcherrima Rensch, 1931, Emerald Green snail, Manus Id., Papua New Guinea: In the past the shells of this species were in demand for making jewelry and were popular with shell collectors. Those factors, plus the fact that their habitat is being destroyed, have led to the species now being considered threatened. Fortunately, it has received protection via CITES.

Submitted by Lindsey Groves

Marine Biodiversity Center

Submitted by Leslie Harris for Marine Biodiversity Center

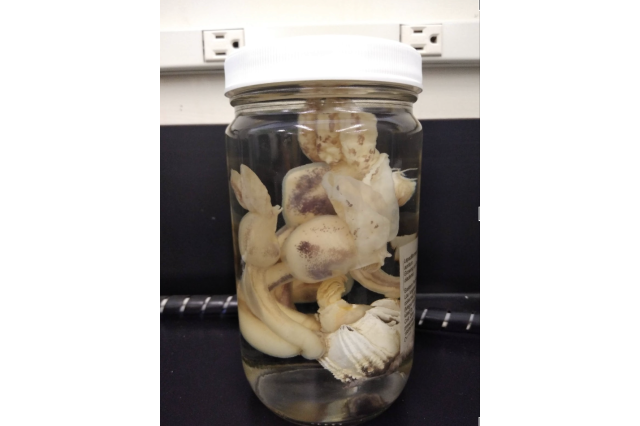

These lumpy bits are not only animals, but they’re members of the phylum Chordata just like us. Styela plicata, a species first introduced to California in 1917 is now a dominant organism in most local harbors. Tunicates are ecosystem powerhouses. They feed on tiny nutritious particles and clean their surrounding water by filtering out bacteria, microplastics, and heavy metals. One study estimated that 200 individuals can process nearly 600 gallons of water each day. I chose this species because it’s an example of how species moved around the world by human activities can have both negative and positive effects. On the one hand, Styela plicata has outcompeted the native species present in the early days of Los Angeles and Long Beach Harbors. On the other hand, these tunicates have helped restore areas of Los Angeles Harbor that were once biological dead zones. The pollutant and heavy metals stored in the bodies of our museum specimens can be used to gauge how pollution has changed over time.

Submitted by Leslie Harris for Marine Biodiversity Center

Say hello to one of the southland’s newest residents. In March 2017 observations of this distinctive anemone with a red-spotted body found in La Jolla were posted on iNaturalist. As of August 2021, it’s been recorded on Anacapa Island and as far north as San Luis Obispo County. Its identity was a mystery until 2020 when Anthopleura mariae was described from the Pacific coast of Baja California, Mexico. Is this a case of a species hitching a ride on boats? Another possibility is that it's been here all along and climate change created an environment more favorable for its northward spread. I chose this anemone because it is spreading so rapidly, and we do not know its impact. It highlights the importance of large museum collections like ours which provide historic evidence of marine biodiversity as well as specimens for comparative morphological and genetic analysis to help solve these puzzles.

Image: Anthopleura mariae (LACM-MBC #20052) by Kellie Uyeda, iNat, CC-by-NC

1 of 1

These lumpy bits are not only animals, but they’re members of the phylum Chordata just like us. Styela plicata, a species first introduced to California in 1917 is now a dominant organism in most local harbors. Tunicates are ecosystem powerhouses. They feed on tiny nutritious particles and clean their surrounding water by filtering out bacteria, microplastics, and heavy metals. One study estimated that 200 individuals can process nearly 600 gallons of water each day. I chose this species because it’s an example of how species moved around the world by human activities can have both negative and positive effects. On the one hand, Styela plicata has outcompeted the native species present in the early days of Los Angeles and Long Beach Harbors. On the other hand, these tunicates have helped restore areas of Los Angeles Harbor that were once biological dead zones. The pollutant and heavy metals stored in the bodies of our museum specimens can be used to gauge how pollution has changed over time.

Submitted by Leslie Harris for Marine Biodiversity Center

Say hello to one of the southland’s newest residents. In March 2017 observations of this distinctive anemone with a red-spotted body found in La Jolla were posted on iNaturalist. As of August 2021, it’s been recorded on Anacapa Island and as far north as San Luis Obispo County. Its identity was a mystery until 2020 when Anthopleura mariae was described from the Pacific coast of Baja California, Mexico. Is this a case of a species hitching a ride on boats? Another possibility is that it's been here all along and climate change created an environment more favorable for its northward spread. I chose this anemone because it is spreading so rapidly, and we do not know its impact. It highlights the importance of large museum collections like ours which provide historic evidence of marine biodiversity as well as specimens for comparative morphological and genetic analysis to help solve these puzzles.

Image: Anthopleura mariae (LACM-MBC #20052) by Kellie Uyeda, iNat, CC-by-NC

Submitted by Leslie Harris for Marine Biodiversity Center

Crustacea

Submitted by Leslie Harris for Marine Biodiversity Center

Did you know that barnacles are crustaceans related to crabs, shrimp, and lobsters, eating with their feet—hardly looking anything like their relatives? Some attach to boat bottoms and can be common on rocks. Others only attach to other animals and only on specific species. The Museum’s giant fin whale soaring overhead in the Otis Booth Pavilion probably once carried hundreds of pounds of these two barnacle species on its body as it traversed the seas. I chose these specimens because even the oddest invertebrates are important in what they can tell us. Oxygen isotopes sequestered in their calcium carbonate exoskeletons can be traced to the water masses they came from, charting a whale’s movement from feeding grounds to calving grounds. Looking at the isotopes from fossils enables researchers to determine how whale migration evolved and how whales responded as the climate changed, giving us clues to the future.

Image above: The barnacle Conchoderma auritum on top of the barnacle Coronula diadema, taken from a humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae).

1 of 1

Did you know that barnacles are crustaceans related to crabs, shrimp, and lobsters, eating with their feet—hardly looking anything like their relatives? Some attach to boat bottoms and can be common on rocks. Others only attach to other animals and only on specific species. The Museum’s giant fin whale soaring overhead in the Otis Booth Pavilion probably once carried hundreds of pounds of these two barnacle species on its body as it traversed the seas. I chose these specimens because even the oddest invertebrates are important in what they can tell us. Oxygen isotopes sequestered in their calcium carbonate exoskeletons can be traced to the water masses they came from, charting a whale’s movement from feeding grounds to calving grounds. Looking at the isotopes from fossils enables researchers to determine how whale migration evolved and how whales responded as the climate changed, giving us clues to the future.

Image above: The barnacle Conchoderma auritum on top of the barnacle Coronula diadema, taken from a humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae).

Submitted by Leslie Harris for Marine Biodiversity Center