Vive la Cinema!

Now on view, a new installation in Becoming Los Angeles spotlights the French innovations at the heart of film history

Published February 7, 2024

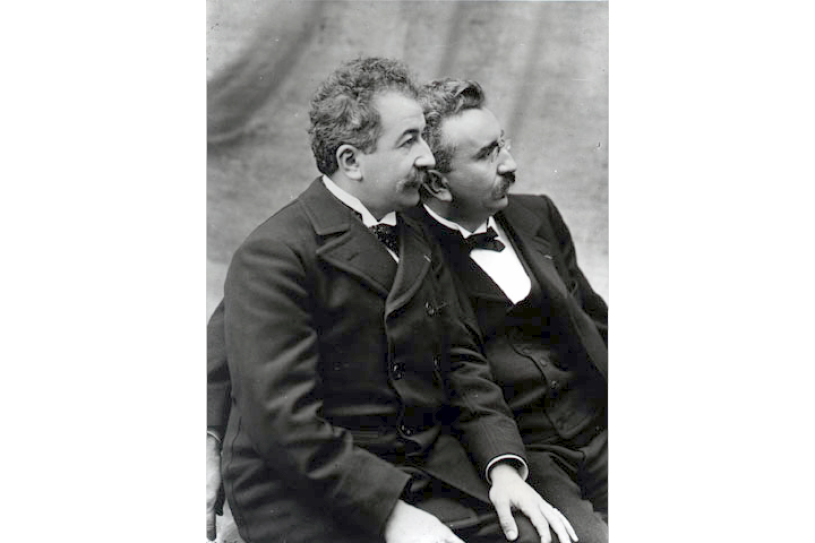

In 1896, so the story goes, the Lumière brothers debuted a short film that frightened French audiences out of their seats.

The 50-second silent film L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat in English) delivered so well on the premise that viewers supposedly stampeded away from the oncoming train. While the fleeing filmgoers may just be a legend, the story persists because it spotlights both the power of film to move people like no other medium—and the very real centrality of French innovation in film history.

“When you think of the film industry and movies everybody worldwide thinks of Hollywood first, but that wasn't the case—originally it was France and French films,” says NHM History Collections Manager Beth Werling. “Not only the film directors, producers, and studios, but also the first successfully manufactured equipment.”

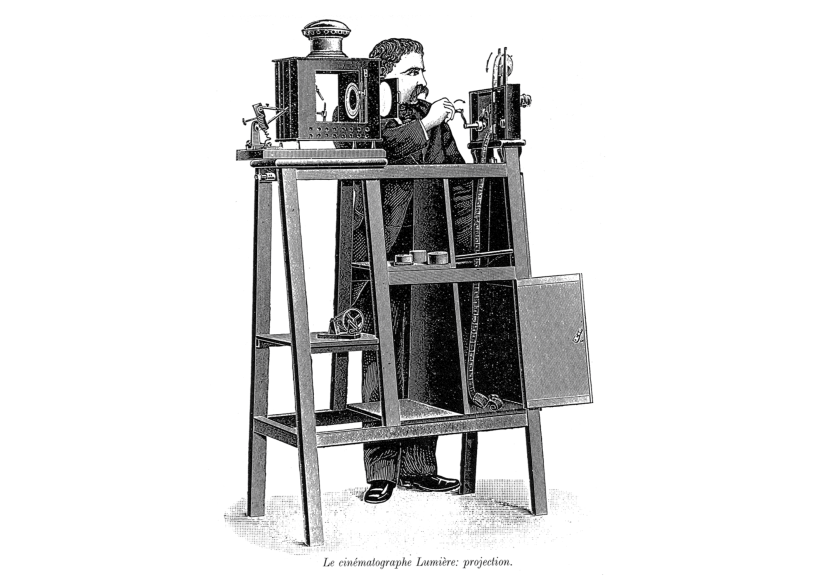

Now on view, the new installation highlights the leading role French innovation played in the birth of the movie business. On display are four French film cameras and a projector that trace the development of film technology. These cameras and projectors would shape the early film industry around the world, with a majority of American studios filming with French equipment.

“The Lumière brothers were the first to develop a movie camera projector and printer that was successful enough to be commercially sold”, says Werling. “It was sold here in the United States—New York and other places—and that was the impetus really for the French developing motion picture technology.”

While famous for their early films, Auguste and Louis Lumière were engineers at their core. Practical design improvements helped their Cinématographe perform better than Thomas Edison’s kinetograph, considered to be the first motion-picture camera. The Cinématographe was smaller and lighter and thus easier to transport and place. Surprising for our electrified times, the hand-crank powered Cinématographe was more practical for shooting on location. Unlike Edison’s earlier device, the Lumières also included a projector that let them showcase their sharper images.

“They did primarily travelogs,” says Werling, making it possible to see the world from a theater seat. “They sent cameramen throughout the world so audiences could see what other people and other nations actually looked like and this was in addition to what were called actualities, which were short films.”

The Lumières made a point of capturing daily life in these actualities, filming their families gardening or playing cards, or factory workers leaving for home at the end of the day. “Their most famous film along these lines was just filming a train coming into a train station and seeing the train coming at you if you were seated in a movie theater. It looked like the train was coming right at you was going to mow you down,” says Werling. “These were all new experiences for people, and it created a cinematic language.”

Courtesy of the Seaver Center for Western History Research

An original Lumiére film strip captures workers leaving the factory. These frames are identifiable as originals (as opposed to later reproductions) by the sprocket holes on each side of the frame.

Courtesy of the Seaver Center for Western History Research

A hand-colored frame depicting a fairy tale couple from one of the Pathé company's narrative films. Pathé acquired the Lumières' patents in 1907.

Courtesy of the Seaver Center for Western History Research

Another hand-colored Pathé film frame, likely from a travelog.

1 of 1

An original Lumiére film strip captures workers leaving the factory. These frames are identifiable as originals (as opposed to later reproductions) by the sprocket holes on each side of the frame.

Courtesy of the Seaver Center for Western History Research

A hand-colored frame depicting a fairy tale couple from one of the Pathé company's narrative films. Pathé acquired the Lumières' patents in 1907.

Courtesy of the Seaver Center for Western History Research

Another hand-colored Pathé film frame, likely from a travelog.

Courtesy of the Seaver Center for Western History Research

While the cinematic language originated in France, world events would shift the heart of the film industry to the United States. “World War I shut down the European studios in Germany, England, France, and Italy—and it left the field wide open for the American film industry,” says Werling. Hollywood would come to dominate the film industry, producing both blockbusters and film innovations to the present day.

“If you look at what defines Los Angeles and Southern California, it's the movie industry, freeways, traffic jams, and palm trees,” says Werling. “So when this Museum was founded in 1910 and opened its doors in 1913, one of the History Department’s missions from the very beginning was to collect artifacts from businesses and industries from the area that define the region and certainly Hollywood has more than any other industry.”