Year of the Snake

Celebrate the 2025 Lunar New Year, Year of the Snake, with highlights from the collection

The Lunar New Year 2025 ushers in the Year of the Snake, which is celebrated in many Asian countries such as China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia. In the story of the Jade Emperor’s race, the snake compensated for his lack of swimming skills by hitching a ride. Unbeknownst to the horse, the snake hid on its hoof. It jumped out as the horse approached the finish line, spooking the horse and winning sixth place. Those born under the Snake are thought to be mysterious, charming, and wise.

Celebrate the Lunar New Year with us as we invite you to slither into a snake-inspired tour through the Museum's collections!

An Introduction to Snakes

Snakes are fascinating creatures with a natural history spanning over 100 million years. They evolved from burrowing or aquatic reptilian ancestors during the Late Jurassic or Early Cretaceous period, gradually losing their limbs to adapt to their environments.

Today, with nearly 3,000 different species, they inhabit diverse ecosystems worldwide. Ranging from deserts and forests to oceans and wetlands, they’ve adapted to a remarkable variety of environments, showcasing specialized behaviors, diets, and physical traits that allow them to thrive.

Snakes at the Museum

Slithering Through History

Beginning the tour is our Vertebrate Paleontology department. Vertebrate Paleontology is the study of ancient animals that have a vertebrate column, otherwise known as a spine or backbone. Our collection is the fifth largest in the nation and a research standard for universities and colleges in the Southern California region.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Vertebrate Paleontology

Mummified Trans-Pecos rat snake (Bogertophis subocularis)

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Vertebrate Paleontology

Mummified Trans-Pecos rat snake (Bogertophis subocularis)

1 of 1

Mummified Trans-Pecos rat snake (Bogertophis subocularis)

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Vertebrate Paleontology

Mummified Trans-Pecos rat snake (Bogertophis subocularis)

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Vertebrate Paleontology

This mummified Trans-Pecos rat snake (Bogertophis subocularis) had been preserved in a cave by the dry heat of the Chihuahuan deserts of New Mexico. Although remaining mostly intact, the snake was last alive during the late Pleistocene age, about 126,000 to 11,700 years ago.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Vertebrate Paleontology

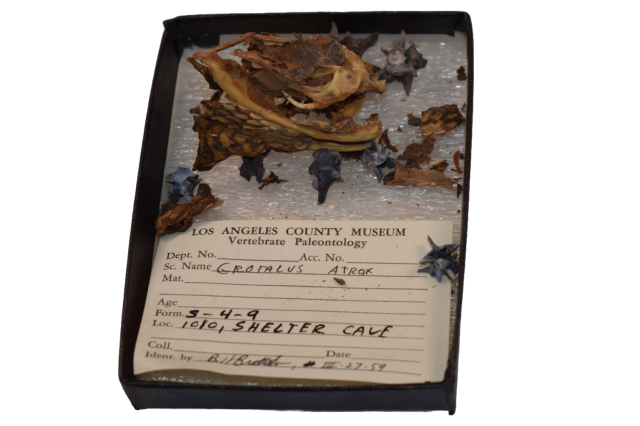

Mummified western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox)

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Vertebrate Paleontology

Mummified western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox)

1 of 1

Mummified western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox)

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Vertebrate Paleontology

Mummified western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox)

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Vertebrate Paleontology

This mummified head of a Western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox), dating back to the late Pleistocene, was discovered in the same cave as the previous snake specimen. Unlike its more docile cave companion, this rattlesnake species is known for its defensive nature, often striking when its characteristic rattling warning is disregarded.

Stone Cold Snakes

Next, we visit the Invertebrate Paleontology Department, which houses and cares for fossils of animals without a backbone (invertebrates), including arthropods (e.g., crabs and shrimp), mollusks (e.g., clams and snails), echinoderms (e.g., sand dollars and sea urchins), and corals as well as ichnofossils—trace fossils of past life. With over seven million specimens, the Invertebrate Paleontology collections rank as the third largest in the United States.

While snakes are vertebrates and so never found in invertebrate collections, ammonites are a common presence in these collections. These extinct cephalopods, related to octopuses and squid, thrived in the oceans during the Age of Dinosaurs.

In medieval Europe, fossilized ammonites were often mistaken for coiled snakes, believed to have been turned to stone by the divine powers of St. Hilda of Whitby or St. Keyne of South Wales and Cornwall in the United Kingdom. These fossils were commonly referred to as "snakestones" or "serpentstones," with traders occasionally carving snake heads onto the wide ends of ammonite fossils to enhance the resemblance.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Invertebrate Paleontology

An ammonite (Nodicoeloceras incrassatum)

Micktherocktapper, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A carved ammonite, made to look like a snake, known as a snakestone or serpentstone. Specimen in the Natural History Museum, London.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Invertebrate Paleontology

Ammonites (Dactylioceras commune) from NHMLAC Collection that highlight how similar the fossilized shell resembles a coiled serpent.

1 of 1

An ammonite (Nodicoeloceras incrassatum)

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Invertebrate Paleontology

A carved ammonite, made to look like a snake, known as a snakestone or serpentstone. Specimen in the Natural History Museum, London.

Micktherocktapper, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ammonites (Dactylioceras commune) from NHMLAC Collection that highlight how similar the fossilized shell resembles a coiled serpent.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Invertebrate Paleontology

Snakeskin Chic

Next, we glide over to the Malacology Department, which focuses on the study of mollusks—a diverse group of animals that includes snails, clams, octopuses, and more. The Museum's malacological collection is global in scope, with a particular emphasis on species from the eastern Pacific Ocean. This extensive collection comprises an estimated 500,000 individual lots, representing approximately 4.5 million specimens. Among the treasures housed here, we encounter several mollusks whose striking patterns bear a remarkable resemblance to the scales and markings of serpents. These species not only showcase the extraordinary beauty of mollusks but also highlight the natural world's interconnectedness through their shared aesthetic themes.

Dr. Jann Vendetti

The Hawaiian snakehead cowrie (Monetaria caputophidii) is among the most common cowrie shells found in its endemic waters near Hawaii. While the juvenile shell, with its muted gray tone and a brown band, exhibits a very subtle likeness, the adult shell develops intricate patterns that strikingly resemble the head of a serpent, enhancing its allure and earning its evocative name.

Gizzardscout, iNaturalist

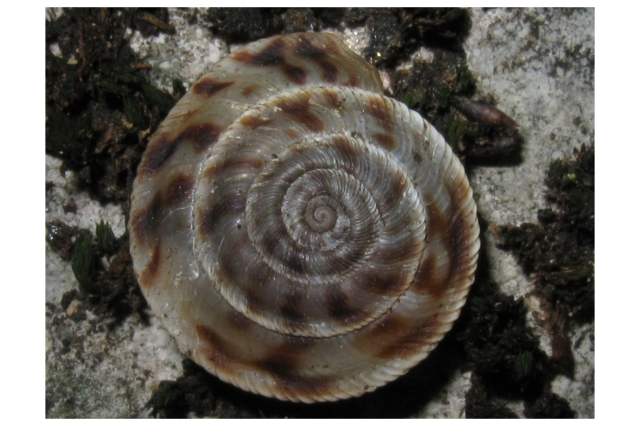

The Painted snake-coiled forest snail (Anguispira picta) is a rare species of air-breathing land snail, found exclusively in a secluded cove southwest of Sherwood in Franklin County, Tennessee. It's six, spotted whorls bear a striking resemblance to a coiled serpent, a characteristic that inspired its descriptive common name.

Martin Predavec, iNaturalist

Snakeskin chiton (Sypharochiton pelliserpentis) is a marine mollusck, in its own class of mollusk called chitons, with a protective dorsal shell. The shell is made up of 8 separate plates, or valves, and encircled by a skirt, known as a girdle. As suggested by this species common name, its girdle is made up of a pattern of overlaying scales resembling snakeskin.

1 of 1

The Hawaiian snakehead cowrie (Monetaria caputophidii) is among the most common cowrie shells found in its endemic waters near Hawaii. While the juvenile shell, with its muted gray tone and a brown band, exhibits a very subtle likeness, the adult shell develops intricate patterns that strikingly resemble the head of a serpent, enhancing its allure and earning its evocative name.

Dr. Jann Vendetti

The Painted snake-coiled forest snail (Anguispira picta) is a rare species of air-breathing land snail, found exclusively in a secluded cove southwest of Sherwood in Franklin County, Tennessee. It's six, spotted whorls bear a striking resemblance to a coiled serpent, a characteristic that inspired its descriptive common name.

Gizzardscout, iNaturalist

Snakeskin chiton (Sypharochiton pelliserpentis) is a marine mollusck, in its own class of mollusk called chitons, with a protective dorsal shell. The shell is made up of 8 separate plates, or valves, and encircled by a skirt, known as a girdle. As suggested by this species common name, its girdle is made up of a pattern of overlaying scales resembling snakeskin.

Martin Predavec, iNaturalist

Serpentine Fliers

It's in the Museum’s Entomology Department that we find our next snake-like specimen. One of the larger collections at the museum, it has approximately six million specimens of insects, spiders, and other terrestrial arthropods. It is the largest in Southern California and has specimens from all over the world. Here we find the snakefly, in the order Raphidioptera.

Serpent Slayer

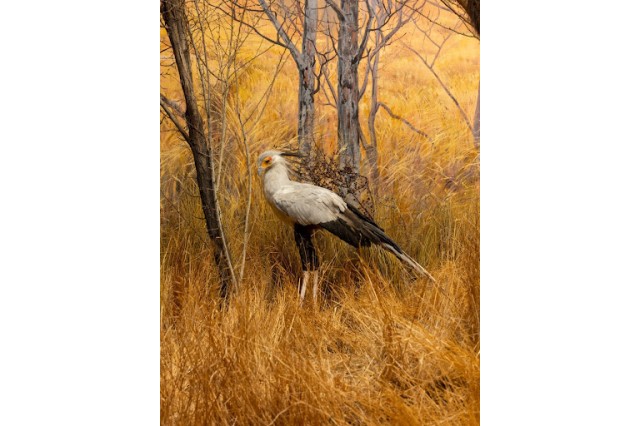

Soaring into the Museum’s Ornithology collections, we encounter a specimen that would haunt a serpent’s dreams. This remarkable bird is one of 121,000 specimens in our collection, representing over 5,400 species. The scope of the collection is particularly rich in species from North America, Africa, South America, and the Pacific Ocean. Among these treasures is the secretary bird (Sagittarius serpentarius), renowned for its lethal kick that makes quick work of snakes.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

The secretary bird, named for the quill-like resemblance of its crest to a pen tucked behind a clerk’s ear, is one of only two terrestrial birds of prey. With their striking long legs, these birds elegantly stalk through grasses, hunting small mammals, reptiles (including venomous snakes), birds, and large insects. Their powerful kick delivers a force five times their body weight in just 10–15 milliseconds—swifter than the reaction time of their slithering prey.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

At the Museum, you can marvel at the secretary bird on display in the African Mammal Hall, where it stands proudly alongside the majestic sable antelope.

1 of 1

The secretary bird, named for the quill-like resemblance of its crest to a pen tucked behind a clerk’s ear, is one of only two terrestrial birds of prey. With their striking long legs, these birds elegantly stalk through grasses, hunting small mammals, reptiles (including venomous snakes), birds, and large insects. Their powerful kick delivers a force five times their body weight in just 10–15 milliseconds—swifter than the reaction time of their slithering prey.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

At the Museum, you can marvel at the secretary bird on display in the African Mammal Hall, where it stands proudly alongside the majestic sable antelope.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Secretary bird (Saggitatius serpentarius)

Henggang Cui, iNaturalist

Meet Rabbit: Our Living Collections Resident

Among the Museum’s many educators is Rabbit, our resident Colombian red-tailed boa (Boa constrictor imperator), who has been a beloved member of the NHMLAC family since 2016. While he may not be covered in fur, Rabbit still lives up to his charming name!

Many visitors are curious about the story behind Rabbit’s unique moniker. Before joining us, Rabbit lived with a previous owner who noticed his fondness for another snake in her care—Ixchel, named after the Mayan moon goddess. In Mayan mythology, the goddess Ixchel is often depicted with a rabbit companion. Rabbit quickly became Ixchel’s steadfast companion, and his name was inspired by their unique bond. The name stuck, and he’s been Rabbit ever since!

Rabbit now serves as an important representative of his species, helping to educate visitors about Columbian red-tailed boas, their habitats, behaviors, and vital roles in the ecosystem. Rabbit is a favorite among guests and staff alike.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Living Collections

Rabbit, the Colombian red-tail boa (Boa constrictor contsrictor), is cared for by the Museum's Living Collections staff.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Living Collections

Rabbit lives behind the scenes but he often guest stars at our special events like Haunted Museum, Dino Fest and our daily 3pm Animal presentations.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Living Collections

Rabbit the boa uses his tongues to collect chemical particles from the air, water, or ground. The tongue's forked shape allows it to pick up odor molecules from two different spots at once. Rabbit then brings his tongue back into the mouth, where it fits into the Jacobson's organ, a special smell sensor on the roof of its mouth.

1 of 1

Rabbit, the Colombian red-tail boa (Boa constrictor contsrictor), is cared for by the Museum's Living Collections staff.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Living Collections

Rabbit lives behind the scenes but he often guest stars at our special events like Haunted Museum, Dino Fest and our daily 3pm Animal presentations.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Living Collections

Rabbit the boa uses his tongues to collect chemical particles from the air, water, or ground. The tongue's forked shape allows it to pick up odor molecules from two different spots at once. Rabbit then brings his tongue back into the mouth, where it fits into the Jacobson's organ, a special smell sensor on the roof of its mouth.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Living Collections

The Study of Reptiles & Amphibians

Wrapping up the tail end of our tour is NHMLAC's collection of amphibians and reptiles containing approximately 195,000 catalogued specimens from around the globe. Herpetology, the study of reptiles and amphibians, includes approximately 3,600 skeletal preparations, 545 cleared and stained specimens, a growing frozen tissue collection, digital and slide photographs, histology slides, and gut contents from a number of species. The associated section library includes a large collection of herpetological reprints.

Caecilians: The Snake-Like Amphibians

Among the intriguing specimens housed here are not only snakes but also their lesser-known amphibian counterparts—caecilians. Often mistaken for snakes due to their elongated, limbless bodies, caecilians differ significantly in several ways. Unlike snakes, which are covered in scales, caecilians possess skin with distinctive folds called annuli. Another key distinction lies in their vision: where snakes have brilles—thin, transparent membranes shielding their eyes—caecilians have minuscule, underdeveloped eyes. These eyes are designed primarily for detecting light and shadow, making them well-suited for their subterranean lifestyles.

Jacqueline Estrada

The ringed caecilian (Siphonops annulatus) is a species endemic to South America. It's believed to have the broadest known distribution of any terrestrial caecillian species.

Jacqueline Estrada

Female ringed caecilians have the ability to produce a milk-like substance to feed their young. Their hatchlings have been known to beg mothers to release more milk, through touch and sound, a behavior that has never been found in amphibians before.

Jacqueline Estrada

These ringed caecilians are preserved in jars of alcohol here in our Herpetology collection.

1 of 1

The ringed caecilian (Siphonops annulatus) is a species endemic to South America. It's believed to have the broadest known distribution of any terrestrial caecillian species.

Jacqueline Estrada

Female ringed caecilians have the ability to produce a milk-like substance to feed their young. Their hatchlings have been known to beg mothers to release more milk, through touch and sound, a behavior that has never been found in amphibians before.

Jacqueline Estrada

These ringed caecilians are preserved in jars of alcohol here in our Herpetology collection.

Jacqueline Estrada

Speed Demons

As we shift our focus to the stars of this Lunar New Year, let’s highlight some of the fastest snakes found within this extraordinary collection. The sidewinder (Crotalus cerastes), a desert-dwelling rattlesnake, holds the title for the fastest snake in the world, achieving speeds of up to 18 miles per hour, using its unique sideways locomotion to traverse sandy terrain with ease. Close behind is the black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis), famed not only for its agility—reaching speeds of 12 miles per hour—but also for its potent venom and elegant, streamlined form.

Jacqueline Estrada

Sidewinder (Crotalus cerastes) in NHMLA's Herpetology collection.

Jacqueline Estrada

A preserved juvenile sidewinder, carefully coiled, rest in the gloved hand of the Senior Collections Manager of Herpetology.

Jacqueline Estrada

Preserved sidewinders in specimen jar at NHMLA

Jacqueline Estrada

Black mambas are named for the black color inside their mouths, which they display when threatened.

Jacqueline Estrada

Preserved Black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) in specimen jar

1 of 1

Sidewinder (Crotalus cerastes) in NHMLA's Herpetology collection.

Jacqueline Estrada

A preserved juvenile sidewinder, carefully coiled, rest in the gloved hand of the Senior Collections Manager of Herpetology.

Jacqueline Estrada

Preserved sidewinders in specimen jar at NHMLA

Jacqueline Estrada

Black mambas are named for the black color inside their mouths, which they display when threatened.

Jacqueline Estrada

Preserved Black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) in specimen jar

Jacqueline Estrada

Black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) in Tshukudu Game Reserve

Marius Burger, iNaturalist

These collections not only celebrate the diversity of our Museum collections but also provide critical insights into their cultural and ecological significance. Whether studying caecilians’ specialized underground existence or marveling at the unmatched speed of the sidewinder, NHMLAC's collection and archives continue to inspire awe and advance scientific understanding.