The Pacific Islands

Faitau itulau ile gagana Samoa

Tapa and woven mats are something that you’re raised on, around, and with [. . .] They have their place in creating sacred spaces whether at a family gathering, faith gatherings, graduations, weddings, funerals or any other important life event. They create dialogue among our community about our cultural ties, our ancestral ties, and our current relations that support and sustain our lives. They are just as much about the future as they are about the current and past relationships that we have nurtured.

—Asena Taione-Filihia (Tongan) and Lolofi Soakai (Tongan)

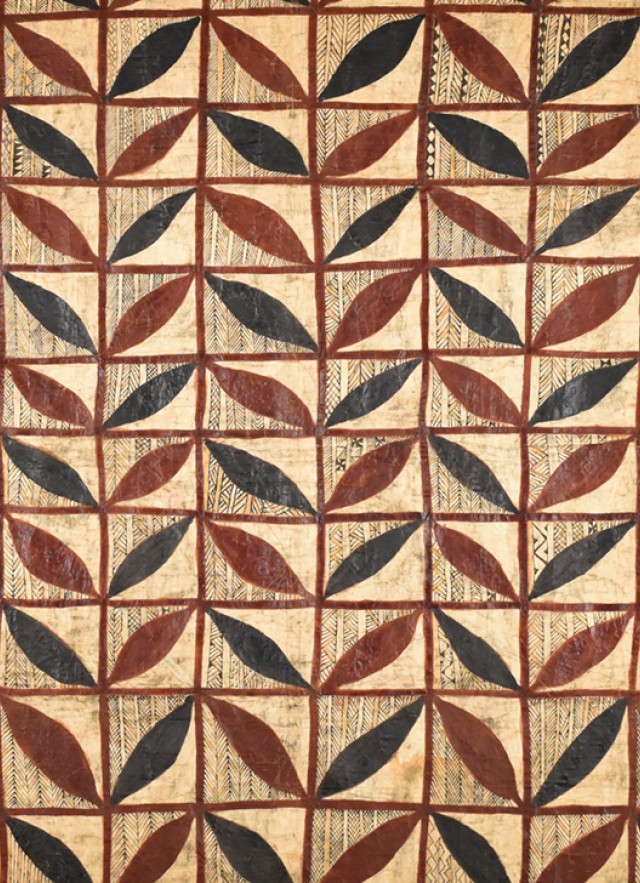

Known by different names in different regions, beaten barkcloth fabric from the Pacific Islands is most commonly called tapa. Along with finely woven mats, tapa were originally used for everything from clothing to ceremonial gifts. Though the creation of these fabrics decreased in the 18th century after the introduction of other textiles from Europe, the tradition of tapa remains strong in Tonga, Samoa, and Fiji, and is experiencing a resurgence in Hawai'i. Known respectively as ngatu, siapo, masi, and kapa, the barkcloth from these Pacific Islands cultures is still used for marriages and funerals, as valued gifts exchanged between families to acknowledge bonds, and in contemporary art.

Historically crafted by women, usually in communal gatherings, these beautiful fabrics take many steps to create. Their designs can be passed among family members or communities living in the same region, and often relate to historical events, the environment, or cultural beliefs.

In many Pacific Island cultures, beating the tapa and adding the design elements is a communal affair. In Tonga, women gather in a 'Koka'anga group.

. . . siapo and 'ie tōga (finely woven mats) symbolize not just family or communal wealth, but Pacific women’s collective power, techniques, and aesthetics.

—Kirisitina Sailiata (Samoan)

While tapa are associated with the Pacific Islands, many cultures also use plant fibers to create mats of various weaves. Finely woven mats are important cultural items for everyday and ceremonial use. Like tapa, they feature in societal rituals such as marriages and funerals, and were also used for sitting and sleeping.

For thousands of years, tapa and finely woven mats have been both everyday and formal items. They have been used as clothing, bedcovers, and room dividers, as well as ceremonial coverings at births, weddings, and funerals. Considered a marker of status and wealth, tapa and finely woven mats were also given as diplomatic gifts and were important trade items. The giving of tapa remains a source of pride and means of honoring the recipient, creating lasting ties.

[Tapa and woven mats] are protective and, to me, symbolize cultural protection and resilience. They mean a connection to a culture and people.

—Katrina Talei Igglesden (Fijian)

The Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County wish to thank the following community members for their support with this project: Audrey Alo, Cindi Alvitre, Juliann Anesi, Katrina Talei Igglesden, Fran Lujan, Kirisitina Sailiata, Tavae Samuelu, Kelani Silk, Lolofi Soakai, Asena Taione-Filihia, and Craig Torres. The Fabric of Community has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH): Democracy demands wisdom. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily represent those of the NEH.