Day of Remembrance: Japanese Angelenos at Manzanar

NHM collections recount the unjust WWII internment of Japanese Angelenos through historic photographs and luggage packed for an uncertain future.

In NHM's Becoming Los Angeles exhibition, visitors can see suitcases that Japanese-American families in Los Angeles brought with them to internment camps.

The trunks were donated by Frances (Ban) Hiraoka, daughter of Reverend Takeshi S. Ban, to include the impact of World War II on Japanese Angelenos in Becoming Los Angeles. The collection of trunks confronts visitors with something familiar– packed luggage–to make forced relocation more of an understandable reality. What possessions would you bring knowing you might never see home or the rest of your belongings again? The luggage emotionally anchors the story of the Japanese Angelenos forcibly removed from their homes and relocated against their will without trial or charges.

A display case in Becoming Los Angeles. Fred Asaichi Hiraoka used the green trunk on the right when he was incarcerated at Manzanar. Fred met his future wife Frances Ban, who owned the large trunk at the back, on the train leaving Manzanar. The metal trunk on the right belonged to Fred Asaichi Hiraoka, and the Early Steamer trunk in the back belonged to Frances Y. (Ban) Hiraoka.

Jenn Berger

Unevenly cut strips of wood and metal, mismatching hinges and bottlecap feet suggest that Takeshi S. Ban fashioned the smaller of the two green trunks while he was incarcerated in a concentration camp using whatever material he could get his hands on.

The two trunks in the previous image, labeled T.S.B., belonged to Reverend Takeshi S. Ban—(1884-1956)—pictured here with his wife. He was a leader in Los Angeles's Japanese-American community.

Yuki Llewellyn, a Japanese-American child in Los Angeles, going to an internment camp in the Owens Valley during World War II. This photograph, and historical artifacts related to the Japanese internment, are on view in NHM's Becoming Los Angeles exhibition.

1 of 1

A display case in Becoming Los Angeles. Fred Asaichi Hiraoka used the green trunk on the right when he was incarcerated at Manzanar. Fred met his future wife Frances Ban, who owned the large trunk at the back, on the train leaving Manzanar. The metal trunk on the right belonged to Fred Asaichi Hiraoka, and the Early Steamer trunk in the back belonged to Frances Y. (Ban) Hiraoka.

Unevenly cut strips of wood and metal, mismatching hinges and bottlecap feet suggest that Takeshi S. Ban fashioned the smaller of the two green trunks while he was incarcerated in a concentration camp using whatever material he could get his hands on.

Jenn Berger

The two trunks in the previous image, labeled T.S.B., belonged to Reverend Takeshi S. Ban—(1884-1956)—pictured here with his wife. He was a leader in Los Angeles's Japanese-American community.

Yuki Llewellyn, a Japanese-American child in Los Angeles, going to an internment camp in the Owens Valley during World War II. This photograph, and historical artifacts related to the Japanese internment, are on view in NHM's Becoming Los Angeles exhibition.

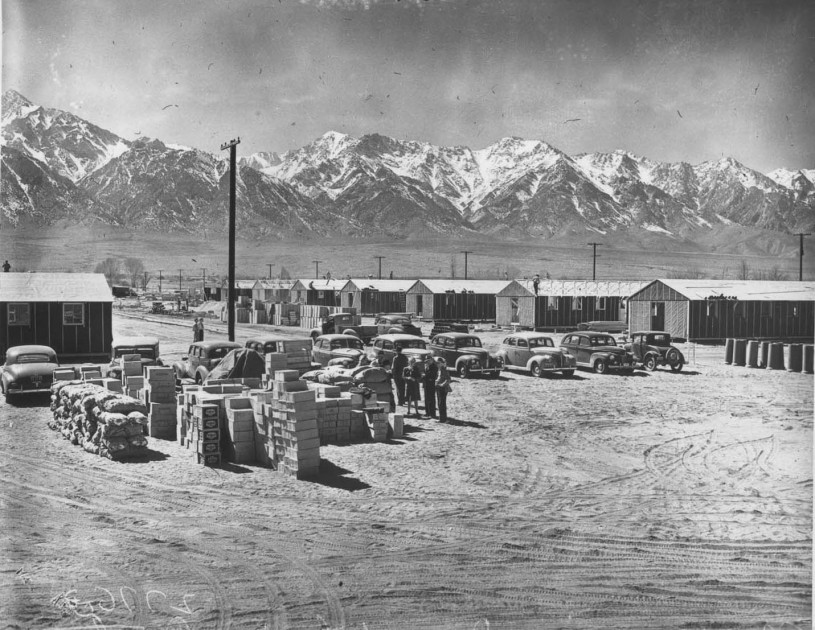

The simple truth is the camp was no more ready for us when we got there than we were ready for it. We had only the dimmest ideas of what to expect.

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, Farewell to Manzanar: A True Story of Japanese American Experience During and After the World War II Internment

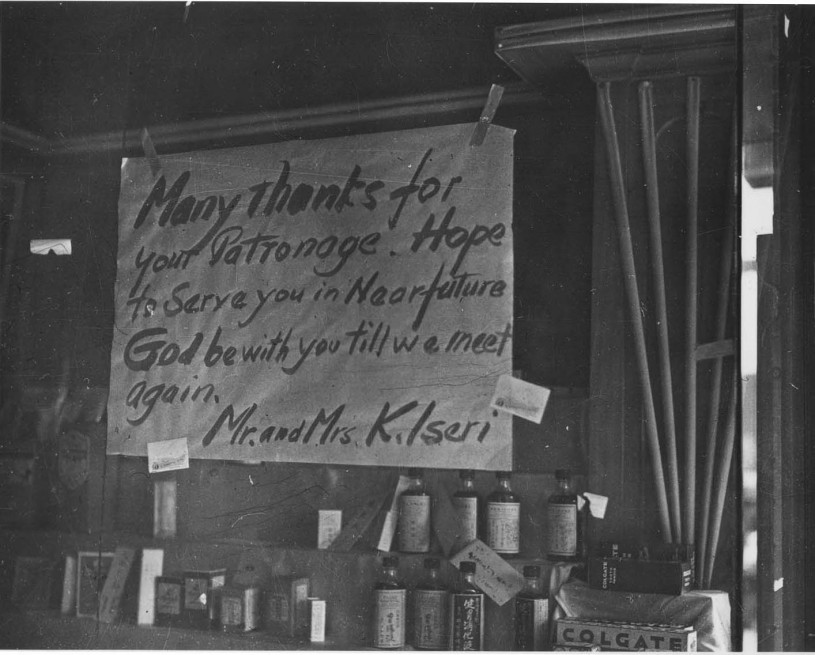

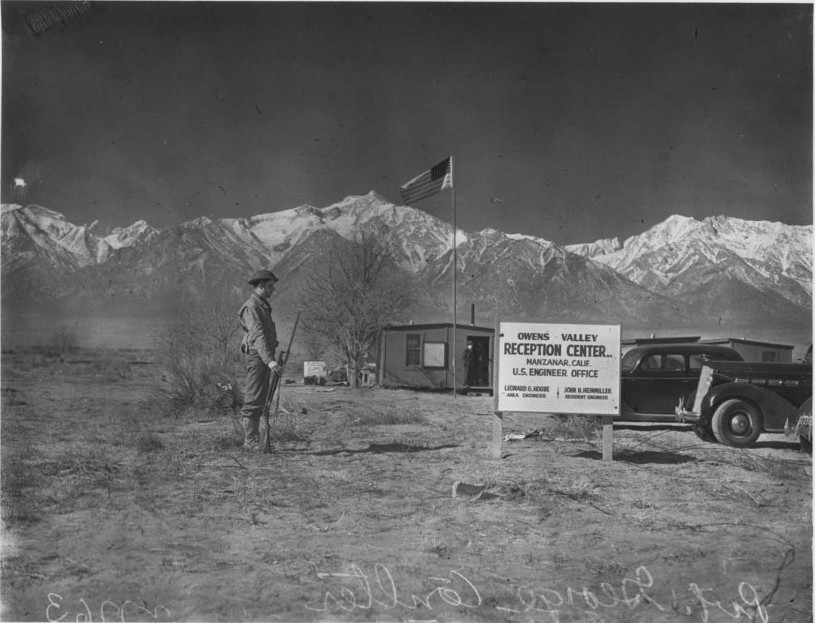

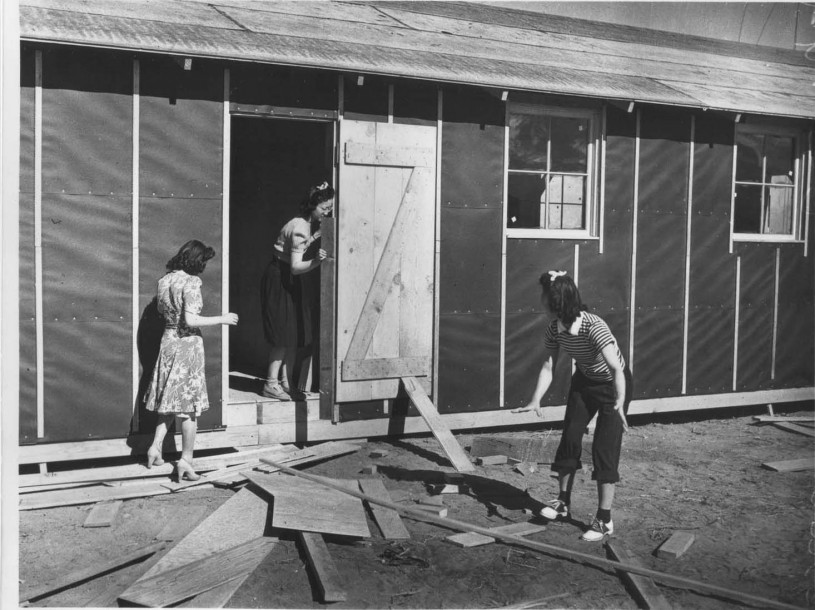

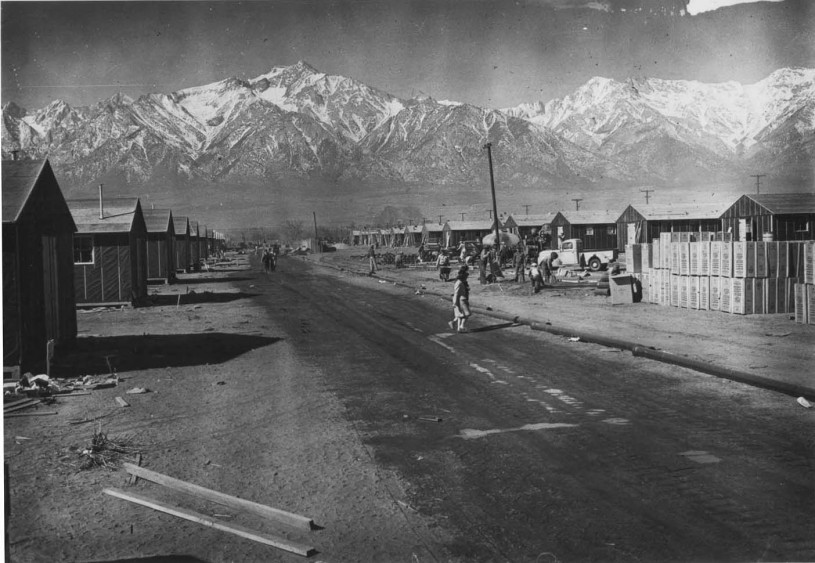

The black-and-white photographs below from the Seaver Center for Western History Research at NHM capture moments both disturbing and heartwarming, showcasing the ease with which a democratic society turned on its citizens and the resiliency of the people so wronged by their government.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, and the United States government forcibly removed more than 120,000 Japanese Americans from their homes along the West Coast in Oregon, Washington, and California, in a shameful cowing to racist hysteria surrounding World War II. Japanese Angelenos were incarcerated in Manzanar and other concentration camps like Heart Mountain in Wyoming, Rohwer in Arkansas, and Poston in Arizona.

NHM's 1971 exhibition Manzanar: Story of a Concentration Camp explored the internment camp through photographs by L.A. photographer and internee Toyo Miyatake, including the black-and-white photos above and below. Miyatake was able to hide a lens in his pocket, slipping it past guards. He went on to construct the rest of his camera from materials found at the internment camp.

An ally smuggled in film, letting Miyatake capture life in Manzanar for posterity. More than half the photographs used in the exhibition were Mr. Miyatake's.

While his photography in Manzanar began in secret, Miyatake would go on to talk his way into becoming the internment camp's official photographer, letting him photograph Japanese Americans who'd volunteered to fight in the war before leaving for service and commemorate momentous occasions, like weddings. Photography was still initially not allowed by internees, so Miyatake would frame the shot, arrange the subjects, and set up the camera, but a white person would have to push the button.

After the war, Miyatake reopened his Los Angeles studio in Little Tokyo, working alongside all of his children who have kept the studio running since his death in 1979. The studio operates to this day, run by Miyatake's grandson at a new location in San Gabriel, California.

The forced evacuations forever altered the landscape of farming in California, where Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans had a tremendous presence, making up, for example, almost 80% of all strawberry farming within L.A. before the war. In the Fall 1971 issue of NHM's magazine Terra, then History Curator William Mason wrote about Miyatake's photographs. Touching on horticulture within Manzanar and the cruel absurdity of the camps, Mason wrote: "The Issei, or Japan-born oldsters, had their moments of satisfaction, too. They were able to grow guayule plants from mere seedlings into mature plants in a fraction of the time estimated by the government. They did so by caring for the plants in a nursery where each plant received much attention and intensive work. The product of their work was the production of synthetic rubber, badly needed by the U.S. during World War II. It is ironic that these men worked so hard for a country which would not permit them to become citizens."

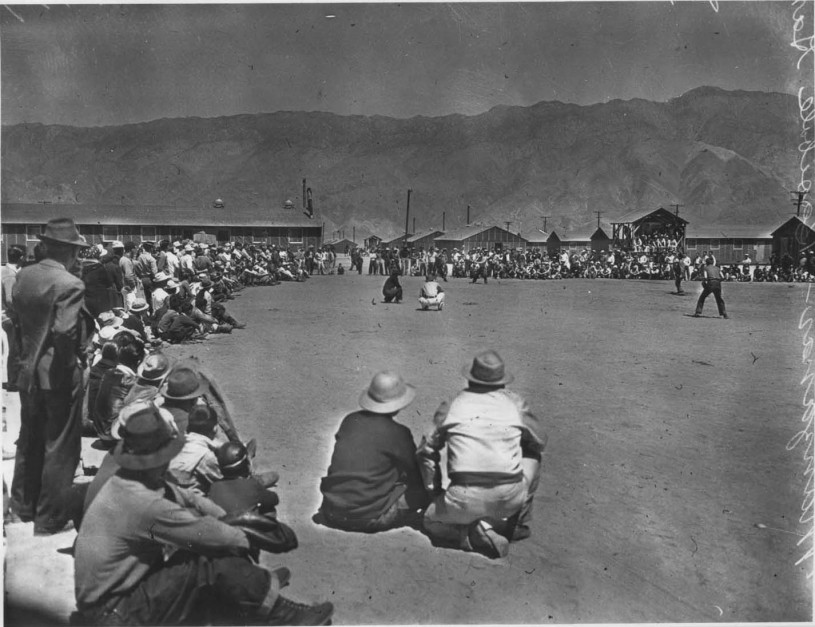

The first of ten internment camps ultimately constructed to house Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals, Manzanar was erected in the shadow of the High Sierras between the towns of Independence and Lone Pine, the largest "town" in Inyo County during its existence.

Citing the above photo, Mason wrote: "One outlet for much of Manzanar's population was baseball. Enjoyed by young and old alike, it was one of the events which helped to relieve the boredom of incarceration. This was the great problem for many people who were accustomed to working hard and who had often been self-employed. There was not enough to do, and time went slowly. In that respect, Manzanar was like any other concentration camp."

The reason I want to remember this is because I know we'll never be able to do it again.

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, Farewell to Manzanar: A True Story of Japanese American Experience During and After the World War II Internment

Los Angeles County, along with the state of California, communities across the country observe a Day of Remembrance on February 19th, the date of Executive Order 9066. Learn more about Manzanar at the National Park Service website and dig deeper into the incredible photographic history of Los Angeles and more at NHM's Seaver Center for Western History Research.