Dive Into the Weird Miocene World of Aquatic Sloths

A new paper by an international team of researchers, including NHM's Curator of Marine Mammals, Dr. Jorge Velez-Juarbe, uncovers more secrets of aquasloths with one of the most complete skeletons ever discovered

Published October 2, 2025

Things got weird for mammals during the late Miocene epoch (roughly from 11.6 to 5.3 million years ago), especially for marine mammals.

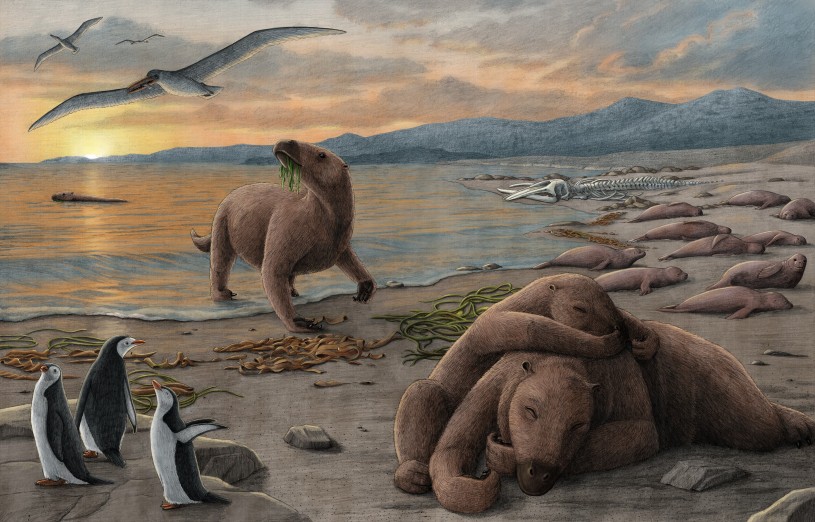

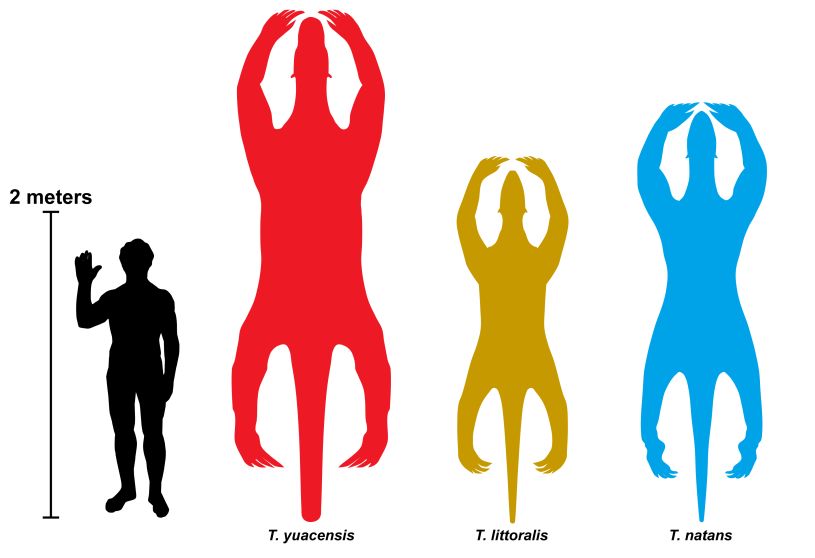

“The South Pacific is particularly interesting because there's a lot of normal-sized animals closely related to modern species, but there's also mini versions,” says Dr. Jorge Velez-Juarbe, vertebrate paleontologist and Curator of Marine Mammals at NHM. “There's a mini version of a true seal, pygmy sperm whales, and smaller versions of baleen whales.” And on top of that, there were aquatic sloths: the genus Thalassocnus. “Currently, there are five known species of these sloths, which, over time, show an increase in aquatic adaptations.”

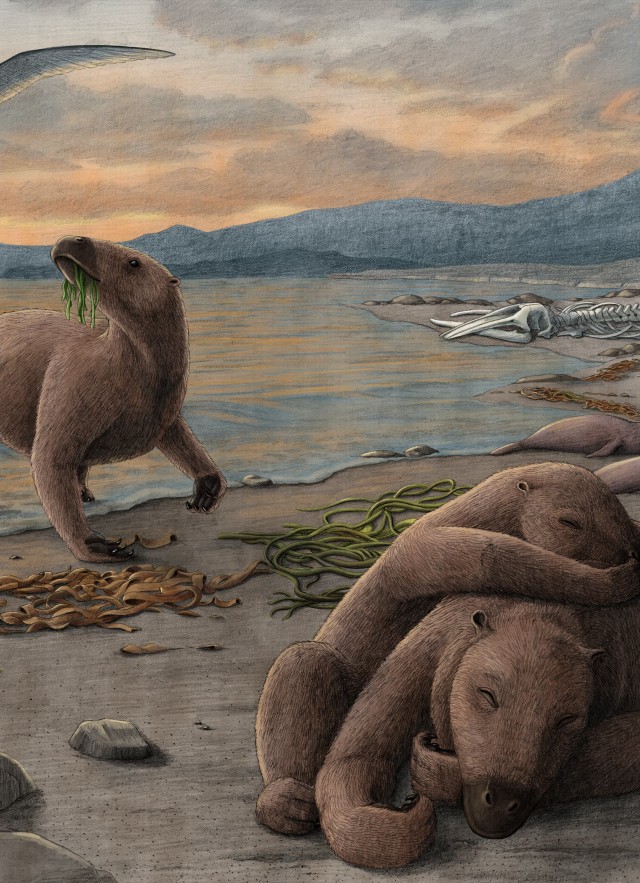

Along with an international team of researchers, Dr. Velez-Juarbe described one of the most complete skeletons yet found in Chile of these peculiar creatures, Thalassocnus natans, in a new paper published in the journal Peer J.

“They were not as large as some of the sloths from La Brea Tar Pits,” says Velez-Juarbe, but the newly-described fossil reveals big changes in the bodies of these aqua sloths. Finding fossil skeletons this complete is incredibly rare, and one of the benefits is a clearer picture of how these strange animals pursued life in the water. The new paper describes the skeleton in detail, including some adaptations for life at sea, some of which bring this sloth’s bones more in line with sirenians, the group of mammals that includes dugongs and manatees, commonly called sea cows. “Animals like dugongs have bones that are dense and bloated to help when they're diving, like a human diver might use a weighted belt. It gives them what's called neutral buoyancy, which means they can go up and down with relative ease.”

Some of these swimming sloths’ adaptations included denser bones like sea cows, but that wasn’t the only one. “You can see it in one of the ankle bones—the shape is changed completely over time, being more evident in later species,” says Velez-Juarbe. “When we think of ground sloths, many of them walk kind of like on the side of their palms, and that's true for the earlier species of Thalassocnus, but as they progress over time, their hind feet in particular become more plantigrade (flat, basically), and we think that made it easier for them to swim.” The one described in this recent work is one of the earliest species, so it doesn’t show some of these adaptations yet.

The researchers behind the paper think aquatic sloths were doing down south what the equally strange desmostylians—imagine a sort of longer-limbed hippo kind of (or visit the L.A. Underwater exhibit to see one in action)—were doing off the coast of North America. Both animals were probably munching on as many marine plants as they could get.

“The North had sea cows and desmostylians, and the South had sea cows and Thalassocnus,” says Velez-Juarbe. “It is mindblowing to think that a few million years ago, there were multiple species of herbivorous marine mammals along the Pacific coast of North and South America, but none nowadays.” The researchers found that aquatic sloths never reached the body size of their northern counterparts, highlighting once again how fascinating and strange marine life in the Miocene was—and hints at how much we still have to learn.