Nature Gardens Turn 10

A look back—and forward–at all the nature thriving in NHM’s Nature Gardens.

Published June 7, 2023

Ten years ago, on June 9, 2013, the Nature Gardens opened to the public.

After years of construction—crushing the asphalt parking lot into mounds of rubble, digging and smoothing out tons of dirt, seeding and planting, and building a long stretch of wooden paths across the 3.5-acre space, a verdant urban oasis emerged, one that would transform the visitors’ experience of the Natural History Museum forever. It was an inspired collaboration between NHM scientists and landscape architects, Mia Lehrer + Associates (MLA), a visionary firm that carefully selected plantings to attract birds, ladybugs, and other native wildlife, making the gardens a living exhibition and place of discovery. It was a spectacular way to celebrate the Museum's 100th birthday.

At the time, Kimball Garrett, current Emeritus and long-time Collections Manager of Ornithology, summed up the purpose of the place perfectly. “The idea of the Nature Gardens,” said Garrett, “is to help people see the surprising diversity, fascinating biology, and life history that’s going on, literally, right in their urban park, schoolyard, or their own backyard.”

The Museum’s horticulture experts extended the invitation to the flying and scampering wildlife in the city by planting more than 600 species of native and nonnative plants that mirrored the region's semi-arid Mediterranean climate. These botanical directors planted a meadow, a pond, edible garden, bird viewing platforms, and walking paths that hugged existing trees including oaks and sycamores. Then, they waited.

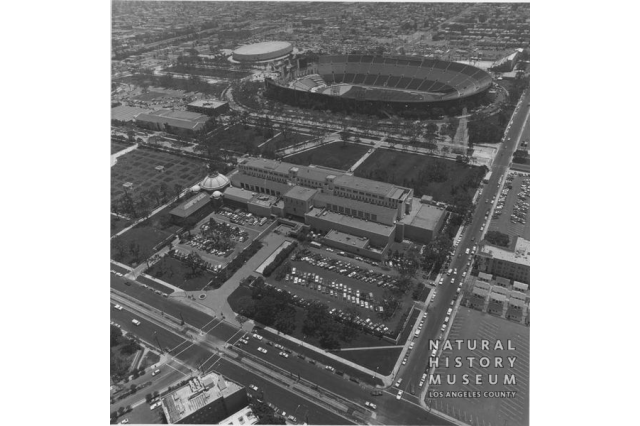

This bird's eye view of Exposition Park during the 1984 Olympics shows why the site was less attractive to animals like birds than it could be. Lawns and parking lots would give way to a thoughtfully planned habitat for urban nature.

Photo courtesy of the Seaver Center for Western History Research

Photo by Cathy McNassor

Bulldozers and earth movers prepare the grounds for the living exhibition to come.

Photo by Cathy McNassor

As many long-standing trees as possible were kept in place even as the former parking lot transformed.

Photo by Cathy McNassor

Rubble obscures the Museum building as the transformation continues.

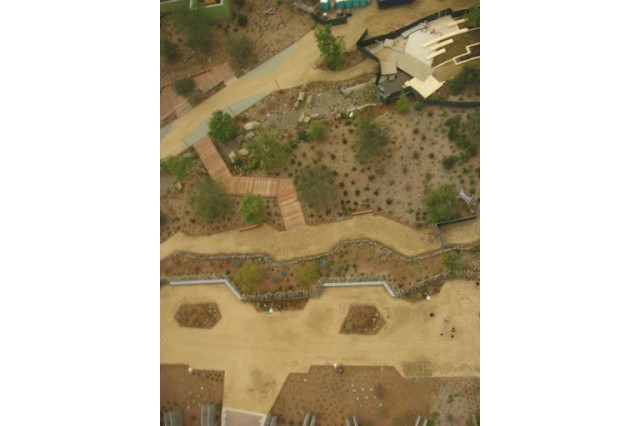

The careful planning behind the planting becomes clear in this aerial shot.

That carefully planned landscape manages to feel wild, attracting urban animals for NHM guests and researchers to observe.

1 of 1

This bird's eye view of Exposition Park during the 1984 Olympics shows why the site was less attractive to animals like birds than it could be. Lawns and parking lots would give way to a thoughtfully planned habitat for urban nature.

Photo courtesy of the Seaver Center for Western History Research

Bulldozers and earth movers prepare the grounds for the living exhibition to come.

Photo by Cathy McNassor

As many long-standing trees as possible were kept in place even as the former parking lot transformed.

Photo by Cathy McNassor

Rubble obscures the Museum building as the transformation continues.

Photo by Cathy McNassor

The careful planning behind the planting becomes clear in this aerial shot.

That carefully planned landscape manages to feel wild, attracting urban animals for NHM guests and researchers to observe.

If You Build It, Will They Come?

Before the parking lot had been dug up and a single plant had taken root, Museum researchers were looking for lizards in the Exposition Park area as part of NHM’s first community science project, Lost Lizards of L.A.—they found very few of the scaly critters despite their being relatively common in other parts of the County.

While the Museum’s Living Collections team could bring in species like the Arroyo chub (a native SoCal fish once common in the L.A. River and now viewable in the Pond) and the Horticulture team choose native plants that would likely bring along or attract local pollinators, no one was sure if other local wildlife would make use of the new habitat, and if so, to what extent. It would be a great place for humans to visit, but what about the animals?

Folks, they came. Local animal Angelenos of all kinds flew, crawled, hopped, fluttered, and buzzed into the Nature Gardens.

“The Nature Gardens were built as an invitation to local wildlife, through carefully selected plantings, to populate a new green space where visitors and scientists can study and experience our urban ecosystem and learn about the amazing biodiversity that surrounds us,” says Daniel Feldman, Senior Manager of Horticulture who oversees the Nature Gardens.

Garrett, who also served on the habitat team, says they created a much better habitat for birds. “What was missing was a shrub layer, any kind of dense shrub layer, and any vertical stratification of the plants.”

The varied height of possible perches, riparian habitat (waterside spaces like the pond and creek), the ample coverage of brush and debris, and the plethora of pollinator-friendly plants have meant a tremendous amount of native insects, mammals, birds, and yes, lizards, have found their way to the Nature Gardens. Except for snails.

"Snails don’t fly,” notes Dr. Jann Vendetti, Associate Curator of Malacology at NHM. “We are stuck with the species that were brought into the Nature Gardens as they were developed, and they were all introduced.”

Even with that limitation, Community Science Senior Manager and member of the habitat team, Lila Higgins made a discovery early on: the first California record of the non-native southern flatcoil snail, Polygyra cereolus. The only new snails that make it into the Nature Gardens are introduced non-natives tagging along on new plants.

NHM researchers and staff recorded what they saw, filling more traditional records like the weekly bird survey done by Garrett for almost the entirety of the first ten years and taken up by his successor, current Ornithology Collections Manager, Dr. Young Ha Suh.

Projects like BioSCAN led by Entomology Curator Dr. Brian Brown and then- Entomology Collections Manager Lisa Gonzalez (Program Manager of Living Collections) captured some of the stunning insect diversity of L.A. County, even discovering a new species of smoke fly.

As a beacon of community science, it’s only fitting that the Gardens have become their own project on iNaturalist, where the current record leader for observations is the relatively new NHM staff member Dr. Vijay Barve, DigIn Digitization Project Manager. Barve has a passion for butterflies and bioinformatics—using computer technology to work with biological data.

Insects at the Nature Gardens

iNaturalist observation by Vijay Barve

Reptiles at the Nature Gardens

iNaturalist observation by Vijay Barve

“When you have such gardens, they become a little oasis for all the biodiversity around. And you have the opportunity to really look at and document what's coming there or what's visiting,” says Barve. The Nature Gardens offer an excellent opportunity to document wildlife in terms of frequency and seasonality because they are monitored every day by staff like Barve and even visitors making observations on iNaturalist. “I can record some biodiversity almost five days a week if I'm around, and that gives me the advantage of good time series data.”

Researchers can get an accurate picture of what animals are residents, just passing through, or one-offs along with a better understanding of their life cycles and how they’re changing from season to season over the decade and into the future.

Birds and Mammals at the Nature Gardens

Thanks to weekly surveys, avian Nature Gardens visitors are particularly well recorded. 103 bird species have been recorded, with house finches being the most abundant with 9,354 counted cumulatively and tying with Allen’s hummingbirds for the most frequently recorded having appeared in every survey.

iNaturalist observation by Vijay Barve

“The song sparrow was perhaps the bird species most emblematic of the habitat improvements associated with the Nature Gardens,” says Garrett. “It went from being a very rare migrant in the Exposition Park area to now a breeding species in the garden; it is still very localized within the urbanized L. A. Basin.”

iNaturalist observation by Vijay Barve

14 species of mammals have been documented visiting the Nature Gardens, including bat species recorded with ultrasonic microphones and nocturnal visitors captured on film via camera traps, but none is more prevalent than the eastern fox squirrel.

iNaturalist observation by Vijay Barve

Captured via a camera trap, a possum visits NHM's Nature Gardens. “I wouldn’t be surprised if someday a fox ended up in our gardens,” says Ordeñana. “They’re really adaptable species, they’re tree-climbing canids that are doing well when they have the amount of tree cover that they need.”

iNaturalist observation by Miguel Ordeñana

1 of 1

Thanks to weekly surveys, avian Nature Gardens visitors are particularly well recorded. 103 bird species have been recorded, with house finches being the most abundant with 9,354 counted cumulatively and tying with Allen’s hummingbirds for the most frequently recorded having appeared in every survey.

iNaturalist observation by Vijay Barve

“The song sparrow was perhaps the bird species most emblematic of the habitat improvements associated with the Nature Gardens,” says Garrett. “It went from being a very rare migrant in the Exposition Park area to now a breeding species in the garden; it is still very localized within the urbanized L. A. Basin.”

iNaturalist observation by Vijay Barve

14 species of mammals have been documented visiting the Nature Gardens, including bat species recorded with ultrasonic microphones and nocturnal visitors captured on film via camera traps, but none is more prevalent than the eastern fox squirrel.

iNaturalist observation by Vijay Barve

Captured via a camera trap, a possum visits NHM's Nature Gardens. “I wouldn’t be surprised if someday a fox ended up in our gardens,” says Ordeñana. “They’re really adaptable species, they’re tree-climbing canids that are doing well when they have the amount of tree cover that they need.”

iNaturalist observation by Miguel Ordeñana

Room to Grow

Despite being an urban oasis for native species, the Nature Gardens are still subject to the same pressures that threaten those animals in our neighborhoods. “Without coyotes in the ecosystem, there’s no top-down control on cats,” says Miguel Ordeñana, wildlife biologist and Senior Manager of Community Science at NHM. “Having outdoor cats in the gardens can almost create an ecological trap for animals like birds and lizards that aren’t well adapted to coexist with this predator, the cat.” Successfully introducing long-lost native species like slender salamanders and tree frogs that have struggled or vanished in the face of our urban sprawl will be hampered as long as cats are stalking the garden.

“We have to remember that flower gardens are habitats on steroids,” says Brown, noting that while the flashier animals like big butterflies and hummingbirds are easy-to-spot crowd-pleasers, the breadth of life is a deeper thing, and many of the lesser-known insect species that make a natural ecosystem buzz aren’t identified in surveys—but additions like rotting oak logs could bring them in. Managing the garden grounds to keep both human and animal visitors happy can be a thorny problem, but NHM’s nature experts are thinking long-term, understanding there’s always room to grow.

Inspiration’s Natural Habitat

Of course, the Nature Gardens are more than a habitat, they’re a place to cultivate inspiration and connections with our natural world. Along with Community Partners and nature lovers of all stripes, NHM specialists in community science and outreach have hosted a menagerie of impressive events that bring the public close to nature. They’ve been a program site, a place to test projects and learn how to do research, to train community scientists on iNaturalist, and even become their own iNaturalist project.

Danielle Aparacio

Nature Navigators practicing how to set up a camera trap in NHM Nature Gardens.

NHM's Nature Gardens provide the ideal field training site for initiatives like Community Science's Super Project now in its fourth year.

LEARN CitSci (Learning & Environmental Science Agency Research Network for Citizen Science), an international partnership of community scientists and educational researchers, was one of the many projects hosted at the Nature Gardens.

1 of 1

Nature Navigators practicing how to set up a camera trap in NHM Nature Gardens.

Danielle Aparacio

NHM's Nature Gardens provide the ideal field training site for initiatives like Community Science's Super Project now in its fourth year.

LEARN CitSci (Learning & Environmental Science Agency Research Network for Citizen Science), an international partnership of community scientists and educational researchers, was one of the many projects hosted at the Nature Gardens.

Encountering wildlife in the Nature Gardens can plant a seed in people. We may never discover what it grows into, but the inspiration folks take home with them has an impact on their lives and our shared home.

Take the case of Nature Navigator Rachel Ann, a nine-year-old who attended one of Ordeñana’s camera trap workshops in the Gardens. She was so fascinated by the technology; she requested a camera trap for her birthday—which she received and then used to create an animal guide for her local nature preserve in Altadena. “She’s a better camera trap photographer than I am now,” says Ordeñana. It’s just one example of how NHM’s Nature Gardens have put down roots in the hearts of our visitors and the larger community.

“The Nature Gardens were established under a period of heavy drought in an area that was devoid of native plants from California and much of the wildlife that now call them home,” says Feldman. “Over 10 years and the challenges that accompanied, a web of life has reemerged and lost relationships have been reestablished, like cedar waxwings returning each fall for the red berries of the Toyon, and the leafcutter bees and sand wasps that emerge each year from their nesting sites. Now, you might find community scientists surveying insects for a project, school groups skimming the pond for aquatic life, and visitors enjoying a lunch outdoors under the shade of an oak tree.”

The gardens, through the dedication of our institution and the Horticulturists that care for the space and the scientists that study the comings and goings, are a thriving example of the resilience of nature in ever-changing environments..