Behind the Scenes With The Flesh-Eating Beetles Preparing Museum Specimens

Meet the smallest and possibly most gruesome members of NHM's collection staff: flesh-eating Dermestid beetles. CONTENT WARNING: Specimen preparation is metal. There are a lot of images of dead animals in different states of decay and preparation below.

Published October 3, 2025

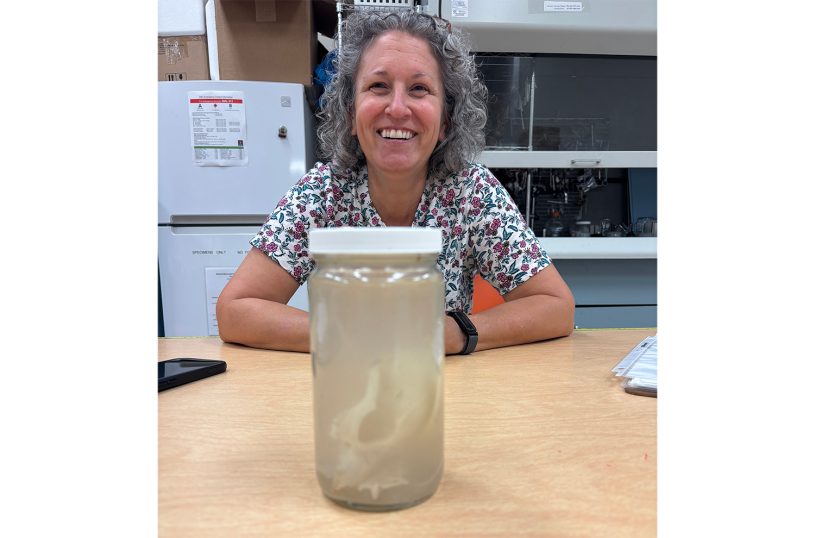

Once a week, NHM’s Collections Manager of Mammalogy, Dr. Shannen Robson, faces her biggest (professional) fear. “I’ve spent most of my career trying to keep bugs away from the collection because they’re one of the worst possible risks to the dry specimen.”

Far from the colorful Joro spiders and dazzling orb weavers in the Spider Pavilion, deep in the bowels of NHM lies the Museum’s insectary, where the spiders and insects showcased at NHM are taken care of behind the scenes. Besides the stars of our seasonal pavilions, there are insects that are decidedly not on display—but they are on staff.

Dermestid beetles are a group of flesh-eating beetles. But whose flesh are they eating? And why? And why don’t they share it with the rest of us? We’ll get to that.

Do you take your specimens wet or dry?

Behind the exhibitions and diorama halls that visitors know and love, the Museum’s collections are no less than a library of all life on Earth. They fuel incredible research that helps us understand our changing planet’s future and past, and instead of books, this library is full of dead animals.

Most specimens that arrive for preparation in the Mammalogy Department are whole carcasses from collection, donation, or salvage. Once the specimen reaches NHM, Robson and other staff record data and decide on how to prepare it, taking measurements and preserving tissues during that process.

Collections of vertebrates like mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles often have whole animals in jars of alcohol to preserve them for researchers into the future. These jarred specimens maintain more information about the specimen for study, things like connective tissue and muscles, for example, and the whole specimen can be CT scanned for further analysis, but Robson notes: “The major limitation there is the jar size. The best way to store a specimen is in glass, and glass is big and heavy, and there's a size limit.”

For a long time, the standard dry specimen preparation for mammals involved keeping the skull and making a study skin, a cotton-stuffed hide that kept information like coat color and facial features for future reference. Though skins and skulls are important, Robson says they’re keeping more of whole skeletons these days to allow researchers to investigate how animals moved in life.

“If we decide to skeletonize it and keep the skull and skeleton, then we take all the large muscle masses, all the organs, all the soft tissue off the carcass until it's basically down to the bone. And then, if it's larger than a raccoon, I'll take it out to the off-site mammal collections center for maceration, which is just putting it in a tank of water and letting bacteria do the work of rotting the remaining tissue and leaving bones clean. And if it's smaller than that, we'll put it in a drying rack and once it’s dry, then feed it to the bugs.”

Dermestid beetles take care of the fine, detail-oriented work of digging through the nooks and crannies of these animal corpses to remove the flesh.

Dermestid beetles derive their name from the Greek word for “skin”, and they're commonly called skin beetles (among other things). The origins of their use in museum specimen preparations definitely starts much earlier, but a 1933 article in the Journal of Mammalogy entitled “Dermestid Beetles As An Aid In Cleaning Bones” lays out their usefulness in the museum field, and how collections managers can start “employing dermestid beetles to remove the flesh”, describing the ideal conditions for the beetles to thrive: “84 degrees Fahrenheit" and “a pan of water placed on a the radiator” for the “necessary humidity”. A warm, steamy room to get the bugs in the meat-eating mood and also stay alive—just happens to perfectly describe NHM’s insectary, where Robson brings the specimens for the final stop on their journey into the collections.

Removing the lingering flesh from these specimens is much more than a good meal; it means that the bones will be ready for storage and study by future researchers. Cleaned skeletons like these are vital for progressing conservation science and anatomical study. Inside the collection, these bones represent population trends, the ranges of animals impacted by things like climate change and habitat loss, and evolutionary changes.

The scoured bones are left with a distinct yellow color, as opposed to the white bones prepared with bleaching agents. These chemical processes take valuable information along with a skeleton’s color. Bleaching destroys organic components of specimens, weakening their structural integrity and reducing their usefulness for genomic analysis. Bones prepared in this way degrade faster, become brittle and are less able to withstand the ravages of time.

Nature's Perfect Undertakers

“Beetle cleaning is the most efficient way to clean a skeleton,” says Robson. “All the other options are either expensive or full of chemicals that either modify the skeleton or make it dangerous for the preparator. If you can get a colony up and running, it's definitely the best option.”

The beetles are a stunning example of preserving natural history with natural means. While solutions don’t get much more elegant, the beetles' work behind the scenes presents its own set of challenges. Unlike other collection tools, they need to be kept alive. Microscopes don’t get parasites or bacterial infections, but the beetles can, so Robson makes sure they don’t get anything raw that can introduce problems. They can also be picky eaters.

Getting the bugs to do their jobs can be more of an art than a science. Collections staff at other institutions have reported soaking specimens in bone broth to whet the beetles’ appetites or ethanol to get them a little tipsy, which Robson notes has no scientific basis, though it does dry out the specimens. Robson has her own secret trick, too.

“I put in a peccary skull down there, and peccaries have this really hard palette on the top of their mouths,” Robson tells me. “The bugs don't like that. But other specimens, like a recent, horribly disgusting, rotten Channel Islands fox, they devoured.” She also swears by “fatty treats”, noting that the beetles particularly like the brain.

For something that’s been used in natural history museums for more than a century, you might think that we know an exhaustive amount about them—not so. Robson notes that it’s not clear why some colonies in museums die off in winter despite being kept completely out of the sun. It’s not even clear what species the beetles are. Research is just getting started to identify the beetles working in museum collections by studying their DNA and gut microbiome to understand how they digest carrion.

They aren’t particularly fast or mobile, but dermestids and some other beetles would threaten collections like Robson’s if they escaped, so NHM staff take special precautions to keep them focused on the right meals. The beetles are kept covered safely in terrariums, and additional enclosures are used when specimens are added or removed. Visitors are strictly limited, and as with the non-native species displayed in the Butterfly and Spider Pavilions, humans are carefully checked for any hitchhiking insects because museum science needs these beetles to stay right where they are, hard at work.

It’s a dirty meal, but someone has to eat it—for science.