Cave Dive Into Arachnids With Dr. Rodrigo Monjaraz-Ruedas, Our New Entomology Curator

Welcome one of NHM’s two new Entomology Curators and explore the secret biodiversity of arachnids deep below the Earth’s surface

Published November 10, 2025

Leer in español

Spiders and scorpions, deep dark caves, advanced mathematics—what many people consider nightmare fuel, NHM’s new Assistant Curator of Entomology, Dr. Rodrigo Monjaraz-Ruedas, calls work.

He’s NHM’s first arachnologist and speleologist (somebody who studies arachnids and caves, respectively) and one of two new curators to join the Entomology Department in early 2025, and he’s gearing up to explore NHM’s collections of arachnids and limestone caves for new discoveries about their misunderstood denizens.

Underground Islands

The prospect of delving into Earth’s dark places and the eight-legged arachnids he primarily researches have never frightened Monjaraz-Ruedas. As a young undergrad, he joined the mountaineering club and started visiting and exploring caves in the mountains of Central Mexico.

“There are a lot of people who have arachnophobia and then claustrophobia, but for me, going into caves was really exciting. That feeling of just turning off your light and then just entirely absolute darkness, it's really good for me. The silence and then listening to drops of water falling. It's kind of really exciting,” says Monjaraz-Ruedas. “So I was never afraid of caves; it was more peaceful just going there. It was pretty relaxing just disconnecting from everything.”

Many of those caves and the biodiversity inhabiting them remain unexplored, and the arthropods—the group of animals that includes insects and arachnids like spiders and scorpions—crawling the cave walls are sometimes found in a single cave and nowhere else on the planet. These insects and arachnids are short-range endemics, animals restricted to small habitats, like caves or specific valleys or mountain meadows (and could also include vertebrates like salamanders or other invertebrates like snails, for example). Monjaraz-Ruedas brought some of the arthropods collected from caving back to his university professors. “They were super stoked about it because a lot of the things I was collecting there were pretty much new species all the time,” says Monjaraz-Ruedas. “Arthropods that are adapted to caves usually don't have coloration, so they're all kind of pale and they have these incredibly elongated appendages.”

Sharing the specimens he recovered from various cave visits with his professors led him to earn a master’s degree and a PhD from the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. He also learned specialized techniques like cave diving to collect specimens from some of the most remote places on the planet.

“From a biological point of view, caves are really unique. Usually, they are completely isolated environments, and they've been playing important roles as refuges for a lot of species during mass extinctions or glaciation events,” says Monjaraz-Ruedas. Animals entered to escape the cold of the Ice Ages, for example, and stayed there, changing over the ensuing millennia into entirely new species. The opening of cave mouths can serve as geological time markers in the evolutionary history of the animals that call them home.

“Caves are like underground island laboratories. They're isolated, and some have their own trophic chain. For example, bats bringing all the poop into the cave creates a whole environment for microarthropods to live there and then a lot of arachnids actually feed on all those microarthropods, and then other bigger animals can feed on those arthropods to create a whole environmental chain and a whole habitat that it's self-sufficient so that there's no need for other external resources other than the bats for example just going outside and inside.”

Understanding these poorly studied short-range endemic arthropods is crucial, because any damage to their habitats could mean the eradication of an entire species. Beyond caves, environmental disasters like wildfires and our changing climate could threaten isolated species in less remote but more vulnerable habitats.

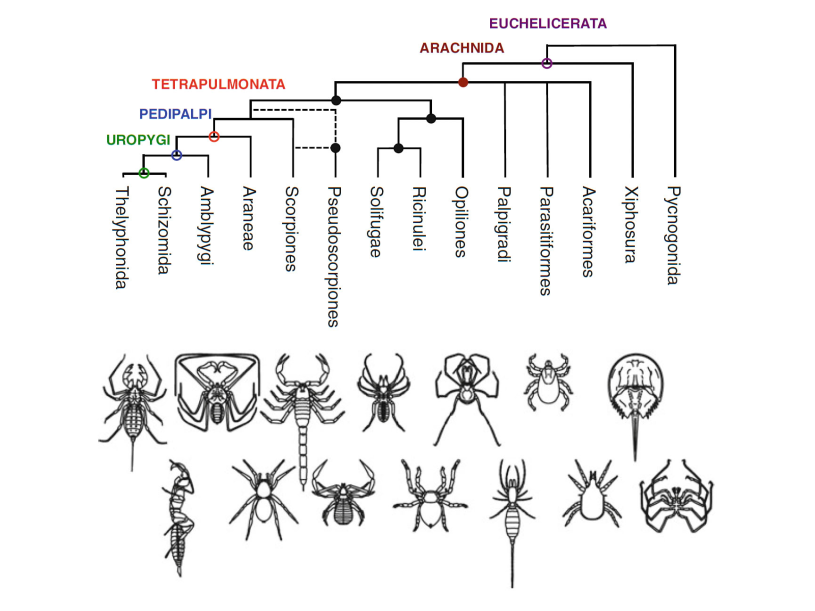

“As part of my current research. I've been working on something that we call the spatial phylogenetics, and what this is looking at is diversity, but from an evolutionary perspective,” says Monjaraz-Ruedas. This involves collecting carefully and examining the biogeographic and evolutionary history, along with phylogenetic trees—diagrams of how closely species are related—to better understand species diversity in a geographic area. This could help make conservation strategies as effective as possible, preserving more genetically diverse species when possible.

“There's a lot of knowledge about that in California for vertebrates and plants, but there's nothing for arthropods,” says Monjaraz-Ruedas.

Tangled Webs of Data

Studying the evolutionary biology and the systematics of short-range endemic species is much more than exploring remote caves. His research combines fieldwork, museum collection data, morphology, and phylogenomics to address specific questions about how new species arise, how we classify them, morphological evolution, and biodiversity. To untangle this complicated web of data, much of his research also emphasizes conservation biology, taxonomy, and bioinformatics, a discipline combining mathematics, statistics, and computer science to solve complex biological problems.

“Statistics are really important in biology,“ says Monjaraz-Ruedas. Biodiversity decline, possible species extinctions, even the relationship between species—family trees called phylogenies—are all hypotheses, or predictions about what’s happening with arthropod life. Building the bases for these predictions means getting as much data from things like physical and digitized museum collections, genetic data, and environmental factors to build complex computer models to then test those hypotheses, all of which means you’re just as likely to find Monjaraz-Ruedas behind a computer screen coding as you are in some cave hunting for blind scorpions.

Spinning Spiders

Most of Monjaraz-Ruedas’ research has focused on poorly known arthropod groups, which have been forgotten by the scientific community and are in desperate need of study. As a result, one of his main goals as curator and researcher is to share his passion for arthropods with the community.

Part of that means curating specimens in the Entomology Collection into a dedicated arachnid collection to be a resource for the arachnologist community. Promoting the collection in this way will help NHM become a recognized leader among arachnology experts and further elevate the collection through ensuing publications and research collaborations.

Monjaraz-Ruedas also wants to capture the hearts of Angelenos in the web of spiders (and other arachnids) by showcasing their incredible diversity and how they benefit us. “Cellar spiders, for example, are common and they’re excellent at controlling mosquito populations," says Monjaraz-Ruedas. “If you kill all the spiders in your house, you’re probably going to start having issues with insects. You can imagine the important role they’re playing in nature more broadly.”

Monjaraz-Ruedas hopes to help people see both how incredible and essential arachnids are for our ecosystems to help shift public perception of these misunderstood creatures from objects of fear to animals in need of conservation, study, and discovery, in line with their value and threatened status in our changing world.