History of Archaeological Research

Archaeological fieldwork conducted by the Anthropology Department staff during the late 1920s and 1970s is responsible for thousands of artifacts housed in our collections. This work was conducted locally both on mainland California and on the various Channel Islands although important work was done in Arizona and Utah. Probably the most significant group of collections comes from Daisy Cave, Big Dog Cave, Dutch Harbor, Mugu, and the Grewe Site in Arizona. It can be divided into five periods.

1926 Expedition to San Nicolas Island

When the Museum opened in 1913 there was no formal Anthropology Department though some of the first acquisitions to the Museum were of an archaeological and ethnographic nature. Museum archives mention that by 1925, C. W. Hatton, was an early Curator of History, and a member of the Museum's "Indian Department," a forerunner of the Anthropology Department.

In 1926, Bruce Bryan was hired as the Museum's first Staff Archaeologist. In that same year, the Museum launched its first archaeological expedition to San Nicolas Island led by Bryan with C. W. Hatton and A. R. Sanger as field assistants. This expedition lasted from October 15 to December 14. The field party conducted surveys and excavations and brought the artifacts back to the Museum for analysis and display. According to a 1926 article in Museum Graphic, a publication of the Natural History Museum, this fieldwork brought back “one of the largest and most complete collections ever obtained from one of the Channel Islands.” This expedition caused a lot of local excitement and a full-page article about it was published in the Los Angeles Sunday Times on February 6, 1927.

Bruce Bryan tried to publish a book on the results of the expedition called the Archeology of San Nicolas Island but it was never published. Eventually in 1970 Bruce Bryan was able to publish a manuscript regarding the 1926 fieldwork through the Southwest Museum, whose collections are now owned by the Autry Museum of the American West.

Early Fieldwork in California and Arizona, 1928-1929

In 1928 Arthur Woodward was hired as a Curator of History and Anthropology. He soon began archaeological field surveys with some limited excavations in California and Arizona. This fieldwork was based on tracing known Chumash village sites gathered from early Spanish historical accounts. This research was confined to private land with landowner permission. While surveying in San Luis Obispo County one of the landowners J. L. Newton put Woodward in contact with one of his friends in Arizona J. A. Christensen who had “Indian Mounds” on his land in southern Arizona. Woodward began survey and excavation at the Christensen Ranch Site during 1929 after securing permission and limited funding from the Museum and the idea that he could recover interesting archeological specimens for the collections. This was a common rationalization for fieldwork at the time.

Woodward was impressed with the results of this fieldwork and recognized that he was dealing with a culture similar to that which H. S. Gladwin in 1928 had uncovered and published on at Casa Grande. Woodward even dubbed the culture he encountered at the Christensen Site the "Casa Grande Culture" since the name Hohokam was not in use as yet. In writing to the Museum's director W. A. Bryan during this first field season, Woodward stated that archeological work in the Gila Valley was important since the area was largely untouched except by Gladwin and the Museum should continue further investigation. Frank Pinkely the Superintendent at nearby Casa Grande at the time and a colleague of Woodward's also encouraged this view.

Van Bergen-Los Angeles Museum Expeditions to California, Arizona, and Utah, 1929-1932

At about this time in 1929 Woodward by a chance encounter met Dr. Charles Van Bergen a retired wealthy medical specialist from New York who had some archelogical experience in Egypt. Dr. Van Bergen made two visits to the Museum in 1929. He enjoyed the Museum so much that he returned for a third time and asked to see the director about sponsoring archeological field research. The director, W. A. Bryan, knew that Arthur Woodward had an interest in archeology and the desire to conduct further fieldwork. W. A. Bryan introduced Van Bergen to Woodward and his offer was promptly accepted.

This chance encounter benefited the Museum greatly. Records indicate that Van Bergen was serious about supporting field research and by the latter part of 1930 he had spent $20,000 of his own money for expeditions to Arizona, California, and Utah. These funds paid for three field vehicles, camping gear, wages, and supplies for 17 men in the field. Quite a sum during the Depression! For his generosity the Los Angeles Museum Board of Governors made Dr. Van Bergen an honorary field associate in 1930 and in 1931 he was made an honorary curator of archaeology.

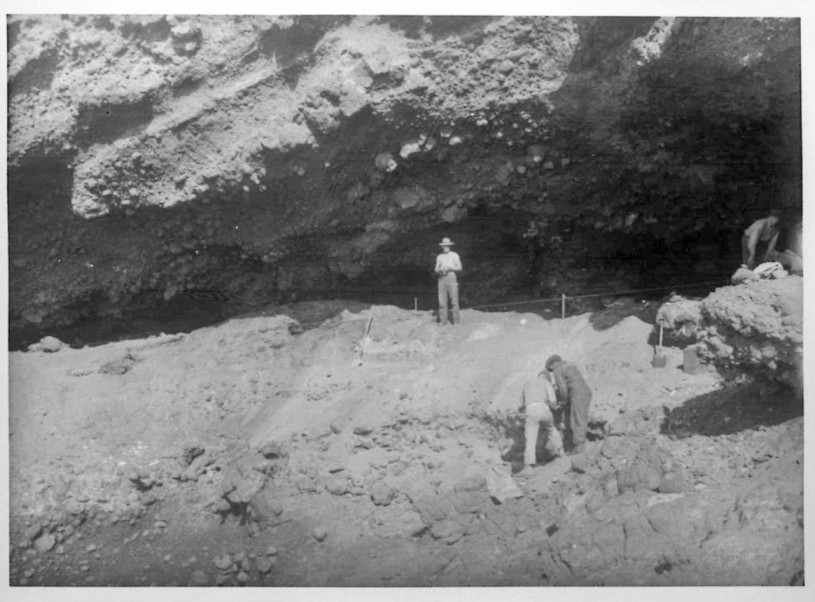

Van Bergen and Woodward's first project was the partial excavation of the Chumash Village of Muwu in Ventura County, California in the fall of 1929. However, by January 1930 Woodward was able to convince his patron Dr. Van Bergen that he should fund field expeditions to Arizona and Utah. This financial backing enabled the Museum to continue archaeological work both in California and in the southwest. Thereafter, field work funded by Van Bergen was known as the Van Bergen-Los Angeles Museum Expeditions or VB-LAM.

Between 1929 and 1932 Woodward participated as a field supervisor in the Van Bergen-Los Angeles Museum Expeditions to California, Arizona, and Utah. During this time, he was particularly well known for his work at the Grewe Site in Arizona, and his excavations in California at Muwu (1929 and then again in 1932), Simo’mo 1932, and Helo.

Unfortunately, the Great Depression caught up with Dr. Van Bergen and he began to experience financial difficulties. The Arizona contingent of the VB-LAM expeditions came to an end in January of 1932 although work still continued in California. Dr. Van Bergen hoped that this would be only a temporary reversal of fortune and planned to get the party back into the field within the next year. However, this did not happen and the VB-LAM expeditions in Arizona were never resumed; by the end of 1932 California operations had ceased as well.

Los Angeles Museum-Channel Islands Biological Survey,1939-1941

From 1939 to 1941, Woodward was involved with the Los Angeles Museum-Channel Islands Biological Survey. This survey involved Natural History Museum staff from various disciplines studying the biology, history, and archaeology of the Channel Islands. Woodward worked on the archaeological sites of San Clemente, San Miguel, San Nicolas, Santa Cruz, and Santa Rosa Islands. The survey proceeded along successfully during 1939, 1940, and throughout most of 1941. With the outbreak of WW II in December 1941 the Los Angeles Museum-Channel Islands Biological Survey came to an end.

San Miguel Island Fieldwork,1960s and 1970s

Charles E. Rozaire began working for the Museum in 1965. Prior to his tenure with the Natural History Museum Charles worked at the Southwest Museum and conducted excavation and testing on San Nicolas and San Miguel Islands.

His primary responsibility upon being hired as a Curator at the Natural History Museum was to create and install a hall depicting Latin American Prehistory, which opened in October of 1966 and closed in 2008.

As his Curatorial duties would permit during the 1960s and 1970s Charles Rozaire conducted extensive research regarding the archaeology of San Miguel Island. Most of this work involved archaeological surveys and the testing of various sites.

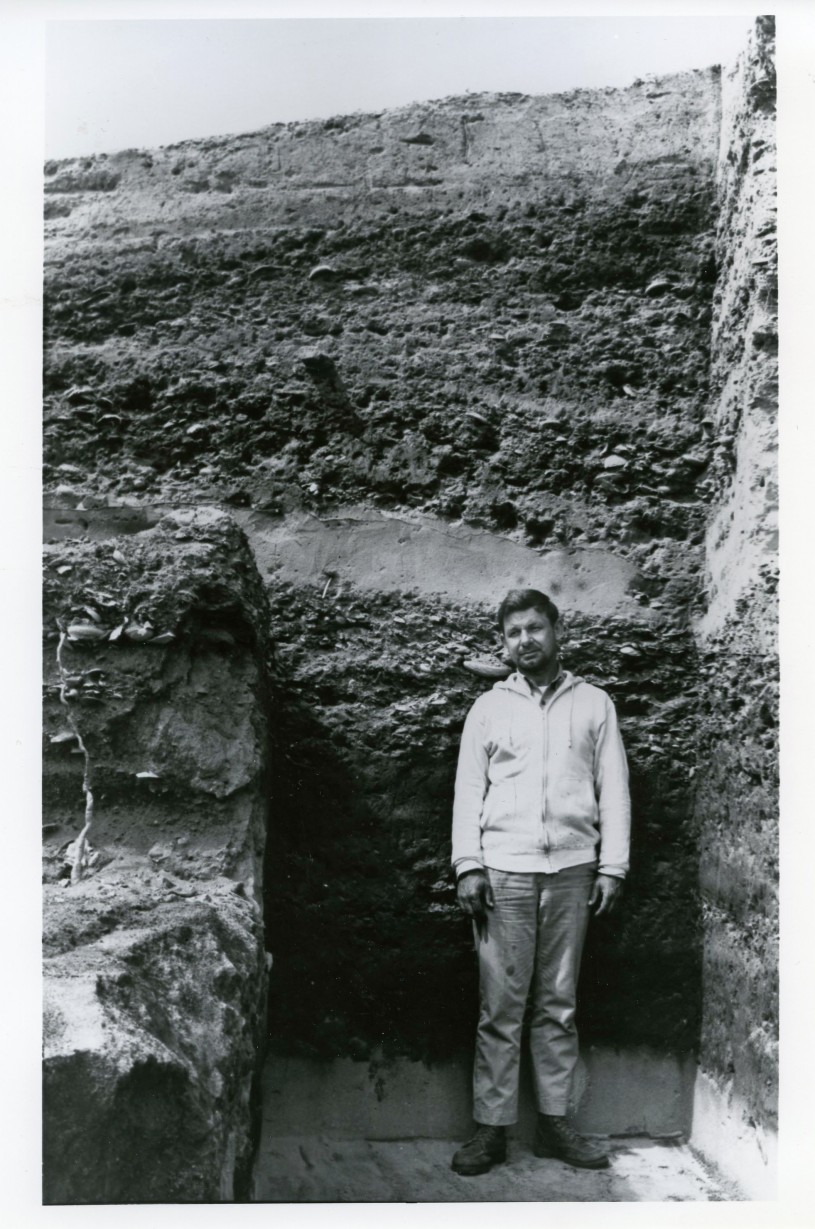

During this work, on San Miguel Island, Rozaire located a cave site he recorded as SMI-261 otherwise known as Daisy Cave. He and his crew partially excavated this site and believed at the time it dated to about 3,000 years ago.

During the 1990s Jon Erlandson from the University of Oregon conducted some additional testing and reanalysis of Rozaire’s work at Daisy Cave and determined that SMI-261 was a very significant site. Erlandson’s analysis indicated that the lowest occupational levels of the cave dated to the terminal Pleistocene at about 11,000 to 12,000 years ago making it one of the oldest cave sites in western North America.

Evidence from the cave showed that the inhabitants were making cordage and basketry, exploited the nearby marine resources for food, and probably would have had watercraft to travel to and from the island.