Backyard Bats

The Bat Roost Count is a community science project led by Miguel Ordeñana and other bat scientists where teams of community scientists watch bat roost sites—where bats rest during the day—to count how many emerge as dusk drifts into night. The project currently focuses on the L.A. River, San Gabriel River, and other locations in LA County. Every year, the first count is timed around the birth of bat pups, and the second count happens when these pups take flight to compare what roost numbers look like pre-pup and post-pup season.

Counting these bats gives biologists, policymakers, and activists important information about bat populations and activity in the city. While community scientists count, researchers take readings of the ultrasonic calls happening outside our human range of hearing using bat detectors. These devices record their calls which are later matched up to species, giving even more crucial information. Learn more about the Bat Roost Count below!

What is the Backyard Bat Survey?

In this project, museum scientists partner with residents in understudied neighborhoods to track and record bat activities for the first large-scale study of bat habitat usage in urban and suburban habitats.

Led by NHMLAC’s Community Science Manager Miguel Ordeñana, the Backyard Bat Survey is an opportunity to broaden awareness and interest in conserving species found in urban areas and to inspire city dwellers to become stewards of the environments in which they live. While most scientific research on wildlife is concentrated in “natural” areas where discoveries are frequent and spectacular, urban areas are often considered not worthy of study. This lack of data, and difficulties in accessing L.A.’s private property and developed landscapes, means there is insufficient information to inform land planning for the benefit of conservation.

Bats play an important role in the world’s ecosystems as seed dispersers, pollinators, and as efficient and successful insectivores, keeping insect numbers at sustainable levels. In Southern California, the majority of bat species are insectivorous and are effective in pest control. Bat colonies eat millions of insects a night, keeping vectors of disease (e.g., mosquitoes) under control and saving the agricultural industry billions of dollars a year in pesticide costs and crop damage. Bats also act as indicators of environmental health. For instance, species like the hoary bat only roost in foliage, allowing their presence or absence in an area to act as a sign of habitat quality. Most bat species are intolerant of urbanization, though 16 known bat species persist in the L.A. area, thanks to special habitat modifications that allow roosting and foraging. Previous local studies focused on large urban wilderness areas, and little is known about bat habitat use of the urban core. In addition to filling major data gaps for the L.A. area, the data collected in this project will be incorporated into the Bat Acoustic Monitoring Portal (BatAMP), providing insights for the broader bat research community to develop an improved understanding of seasonal and migratory patterns across North America.

The Backyard Bat Survey is a project within a larger NHMLAC urban biodiversity study called the SuperProject. In 2016, the Backyard Bat Study joined RASCals (Reptiles and Amphibians of Southern California), SLIME (Snails and slugs Living in Metropolitan Environments), and the Southern California Squirrel Survey to form the NHMLAC's first ever SuperProject. The current phase of the project began in Fall 2018 and features a gradient of sites across Southern L.A., including San Pedro, Torrance, Carson, and Long Beach.

Batters Up!

Join the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Backyard Bat Survey team by finding and sharing bat hot spots and potential roost locations to help our local bats. NHM is partnering with L.A. County residents to track and record bat activity through community science-based acoustic monitoring and roost mapping.

As part of the first large-scale study of bats in urban and suburban habitats, beginning in October 2020, NHM and community scientists will partner with the SoCal Bat Working Group and the USGS to map bat roosts in our local communities. For the safety of the bats,the locations of these roosts will not be shared publicly. Bat roost mapping and monitoring will provide the conservation community with unprecedented information on bat roosts and their structures that can inform conservation-focused policy decisions.

HOW TO PARTICIPATE

1. Locate bat habitat. Bats are most active on warm nights, and are often found near water sources (artificial lakes, reservoirs, pools, rivers, drainages or storm channels), but can also be found in commercial/residential neighborhoods and parks or natural areas with little or no water.

2. Find potential roosts: Go out about 30 minutes before dusk to monitor natural habitat (palm trees, large old trees with cavities, dead trees, cliff faces, rock outcroppings) or human structures (houses, underpass, abandoned warehouse, bridge), parks and hiking areas.

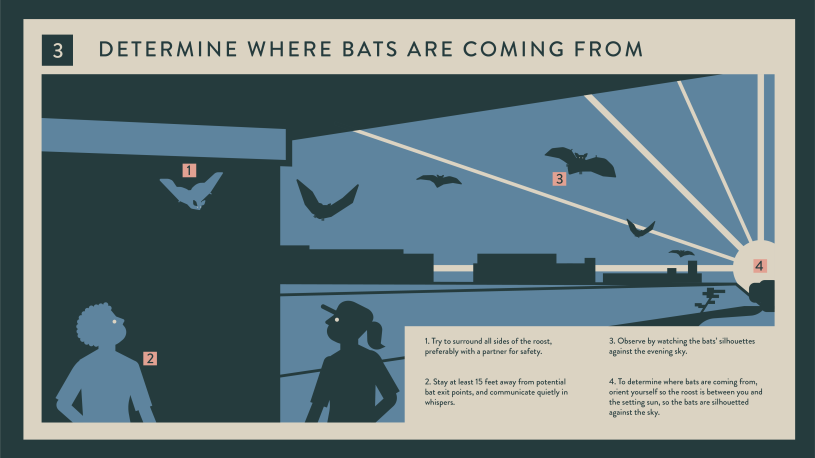

3. Determine where they’re coming from: Try to surround all sides of the roost, preferably with a partner for safety. Stay at least 15 feet away from potential bat exit points, communicate quietly in whispers, and try to observe by watching their silhouettes against the evening sky. to determine where bats are emerging from. Orient yourself so that the roost is between you and the setting sun, to make the bats silhouetted against the sky.

4. Click this link for the bat observation form, let us know what you saw, when and where you saw it, and an NHM staff member will follow up with you within a week.

Thank you and happy batting!

Bats in Southern california Backyards

The most common species of bat in the Los Angeles area is the Mexican free-tailed bat, a medium-sized brown bat with a tail that conspicuously extends beyond the tail membrane. Populations of Mexican free-tailed bats that live in southwestern U.S. migrate annually to overwinter in Southern California and Baja California. Our surveys have documented this species at every location that has detected any bats. A particularly gregarious species, it is often found roosting in huge colonies. Bracken Cave in San Antonio, Texas, is famously home to 20 million Mexican free-tailed bats. The species has narrow wings which limit it to straight, rapid flight. It’s been clocked at speeds of about 100 mph. It feeds primarily on moths, foraging at heights varying from a few feet up to hundreds of feet. Some biologists have noted that Mexican free-tailed bats smell like old Corona beer.

The canyon bat is the smallest bat in the L.A. area, and is the second most commonly detected species in the L.A. area after the Mexican free-tailed bat. Its small body has blonde fur that contrasts with blackish ears and wings. Canyon bats feed on small insects like flying ants, mosquitos and small moths. They emerge early in the evening with an erratic, fluttery flight pattern similar to that of butterflies.

This is the largest bat found in the U.S., with a conspicuous wingspan of up to 2 feet. It ranges from Southern California south to Argentina and east through the southwestern US to Texas. Its large size and narrow wings mean it must launch itself from a high point to gain momentum for flight. Because of this, their roosts are usually 15 feet or more above the ground. They roost in rock crevices, trees, tunnels and human-made structures such as buildings. Miguel and his colleagues with the U.S. Forest Service used a bat detector to document this species in Griffith Park (LA Zoo) near the L.A. River. Western mastiff bats were thought to have been extirpated from the L.A. Basin 10 years before this detection. Since then, Western mastiff bats have been detected in several of our backyard study sites. The presence of the L.A. River and other large bodies of water may be critical to its persistence.

The big brown bat has a wide distribution throughout North America and is one of the most common bat species observed in the Midwest and eastern United States. It is a well-known urban bat that readily roosts in buildings and other human-made structures. Surprisingly, big brown bats have not been detected in our backyard bat surveys as frequently as expected. Our bat researchers are curious why.

The Yuma myotis occurs in western North America from British Columbia to central Mexico, and is highly associated with riparian areas near streams and other water bodies. Their natural roosts include caves, rock crevices and tree hollows, but they can also be found roosting in buildings, below bridges, and just about any human-made structure. They are also opportunistic in their diet, feeding on whatever insects happen to be around.

This is one of several species of myotis, or “little brown bats” that occur in our area, and one of the more commonly detected bats. Despite its common name, the California myotis is actually found throughout western North America, from Alaska to Mexico. California myotis have a wide tolerance of habitat including semi-arid desert regions of the Southwest, arid grasslands, forested regions of the Pacific Northwest, humid coastal forests and montane forests. Locally, the species is associated with riparian zones such as the L.A. River. Fur color varies from light tan to black. This species has a slow erratic flight pattern—making abrupt changes in their path of flight to pursue their insect prey.

Hoary bats have dark brown or black fur with white at the tips, giving it a frosted appearance. They are mostly solitary, preferring to roost alone in trees, rather than in caves. They are relatively large; having a wingspan of more than 12 inches, and are strong fliers that migrate long distances. They travel from the forests of Canada and the Pacific Northwest to southern California and Central America, where they spend the winter months escaping the cold climate of the north. The name Lasiurus means “hairy-tailed” and refers to the fur covered tail membrane that occurs in all members of this genus. Our acoustic bat detectors have documented this species in South L.A. The specimen on display here was collected near the old café at the Natural History Museum (now the location of the Otis Booth Pavilion).

The fur of western red bats ranges from a bright reddish to a pale red color. (In life it’s a beautiful bat; the color of our study skin is somewhat faded.) This bat is mostly a forest dweller and its red color acts as perfect camouflage against the leaves and branches of the trees it prefers as roosts (oaks, elms, sycamores…). This species will migrate to southern areas for overwintering. Our backyard bat surveys have detected this species in South L.A., including in the Museum’s Nature Gardens. This was a significant detection because western red bats are a species of special concern and a foliage specialist, proving the importance of even small green spaces with canopy cover.

Like other bats in the genus Lasiurus, the western yellow bat generally inhabits wooded areas and roosts in foliage, but it will also roost in tree holes and buildings. It occurs in Mexico and the southwestern US. In the US, the yellow bat is often associated with introduced palm trees, particularly when dead fronds remain on the trees. Our surveys have detected western yellow bats in a few backyards near Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area and Magic Johnson Park. Both of these parks have introduced palms.

Silver-haired bats are another forest-dwelling species, found across North America but migrating to more temperate parts of the continent to spend the winter months. They have black fur with white-tips, giving them the common name. Like the other tree bats, they tend to roost in the crags and crevices formed by bark, or inside tree cavities. They feed primarily on moths. Our bat surveys have detected silver-haired bats in backyards in San Dimas and Riverside, which is surprising because this species is usually limited to forest habitats. In fact, the published distribution of the silver-haired bat does not Southern California, making our survey results even more important.

Not as gregarious as the related Mexican free-tailed bat, the pocketed free-tailed bat roosts in colonies of no more than 100 individuals. They emerge from these roosts in the late evening, flying high and fast in pursuit of insect prey, primarily moths. They inhabit rocky cliffs, caves and slopes of the deserts and semi-arid areas of the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico, but also make use of buildings. Their common name comes from the flap of skin that forms a pocket near each leg. The LA region appears to be the northern limit of the pocketed free-trailed bat’s range, with just a few museum specimens from the LA Basin and Orange County. The presence of this species has also been documented by the backyard bat study.

Contact Us

For general inquiries, please e-mail mordenan@nhm.org or call 213.763.3320.

The Backyard Bat Survey is made possible in part by a generous grant from the Disney Conservation Fund